The History of the Bromley-Heath Public Housing Development

Architecture as Public Policy: The History of the Bromley-Heath Public Housing Development

The twentieth century was an epoch of vast experimentation and change. No where can this be seen more than in the design and construction of low-cost housing. The architectural heritage of Jamaica Plain has remarkable examples of the three phases in housing designed and built to be affordable to the working man.

The first was the Sunnyside-Roundhill Streets houses in the factory district of Hyde Square which George W. Pope designed for the Workingman’s Building Association. Financed by the philanthropist Robert Treat Paine, over 100 Queen Anne style wooden homes were built between 1889 and 1891. This was unique because - unlike other philanthropic housing experiments - it was part of a financial institution which Paine organized with $25,000 of his own capital in 1887 called the Workingman’s Cooperative Bank. The bank was a partnership between investors and the workingman. By regular savings, the wage earner could earn interest on his money and, with the bank’s guidance, have enough for the down payment and monthly mortgage.

The second was Woodbourne, in Forest Hills, built by the Boston Dwellinghouse Company between 1912 and 1914. The Paine experiment sought to lower costs by joining the housing program with a cooperative bank. The Boston Dwellinghouse Company intended to lower costs by building a large-scale development ( 30 acres ) with standardized housing units built in clusters. For the first time in any philanthropic housing program, Woodbourne was designed as a whole community with common grounds for playgrounds and a clubhouse. Robert Anderson Pope was the site planner and Kilham and Hopkins were the architects.

The third phase was public housing. In this last phase, entirely new methods of financing, design, site planning and construction were introduced. The most dramatic difference was that it was financed and managed by government.

The Heath Street Housing Development - only a few yards away from Roundhill Street - was one of the first eight public housing developments planned and built by the Boston Housing Authority between 1939 and 1942. It was enlarged with the construction of Bromley Park twelve years later.

I. HEATH STREET HOUSES

Heath Street houses at 25 Horan Way with hip roof, dormers, and entrance hood added in 1996-1997.

In its issue of January, 1941, Architectural Record stated: “ publicly owned housing has become a characteristic feature of American life. It is the most single building type [which has pioneered] new techniques of financing, design, construction and management.”

Jamaica Plain had never before seen anything like the architecture and site plan of Heath Street public housing. It was a separate village of low scale, sleek, repetitive, standardized apartment blocks set at angles to Heath and Walden Streets in a free plan that destroyed the familiar, existing - and chaotic - street patterns.

The Heath Street Development was born out of the catastrophe of the Great Depression. Direct government action in resolving the housing needs of the Commonwealth had always been resisted by private sector investors. But housing became a national issue for the first time in 1932. As the Depression deepened, bank foreclosures on mortgages reached 1000 a day. Massive unemployment virtually stopped home buying in an industry already staggering. ( Home sales began dropping as early as 1926 ). Businessmen began looking to the federal government for help to relieve the construction industry with large scale building program. The April, 1932 issue of Business Week reported that investors were becoming interested in housing developments: “ talk about low cost housing is getting the public excited.”

President Herbert Hoover believed that the responsibility for the eradication of slums and the rejuvenation of home building rested squarely with private business. His administration responded to the housing crisis with two far reaching bills both passed by Congress on July 21, 1932: the Federal Home Loan Act and the Emergency Relief and Construction Act. The first Act - which exists to this day - provided government insured mortgages written by participating banks and lending institutions to take the risk out of home loans. The second provided capital to limited dividend corporations ( much like the Boston Dwellinghouse Company ) which organized to construct low cost housing.

Both were Republican efforts to stave off direct government construction of housing. As Secretary of Commerce Roy Lyman Wilbur wrote in 1932, if the private sector failed to remedy “the evil of slums, housing by public authority was inevitable.”

Wilbur wrote this in the wake of the first housing conference sponsored by an American president held in Washington, D.C. on December 2 - 5 , 1931. Writing in the January, 1932 issue of Architectural Record, Michael Mikkleson reviewed the key findings of the conference; three of the most important were:

That a house in most American cities could not be built and sold for a profit for less than $4,500. This included the lot, street curb cuts and sidewalks and sanitary lines.

To buy this same house, a family would have to earn an income of $2250 a year to make the down payment of $1125.

In a phrase that would be echoed five years later, Mikkleson quoted the well known housing advocate Edith Elmer Wood, who estimated in 1931 that 2/3rds of all American families have incomes of not more than $2000 and 1/3rd have incomes below $1200.

In short, few Americans on the eve of the Franklin D. Roosevelt Administration could afford their own home.

Heath Street houses showing the original flat roofs and courtyard formed by two apartment buildings. The new trees and lawn fencing are part of the 1996-1997 improvements.

The inevitable predicted by Roy Wilbur arrived in the summer of 1933. Facing the failure of the private sector to respond to Hoover’s initiatives, the administration of Franklin D. Roosevelt prepared the way for the last phase in providing housing for the low income family, public housing.

The only previous experience the United States government had with building large scale housing was the Emergency Fleet Corporation and United States Housing Corporation of 1918-1919. With the entry of the United States in the war against Germany in 1917, the housing shortage for defense workers became a national concern.

The production of warships, munitions and heavy equipment on a massive scale never before seen in American history put a huge strain on the housing capacities around defense plants. As a result, war related industry was having a difficult time hiring and keeping workers.

The Wilson Administration considered this a threat to the war effort and on March 1. 1918, the Emergency Fleet Corporation was established ( 65th Congress. 40 Stat. 438 1918 ). It built 21 corporate towns from Maine to Vancouver, one of which was Atlantic Heights in Portsmouth, NH designed by Kilham and Hopkins. In addition 44 townships were built by a second federal entity, the United States Housing Corporation ( USHC ), approved by Congress on may 16, 1918. ( 65th Congress 40 Stat. 550. 1918 ). On July 9,1918, the United States Housing Corporation was organized as part of the Bureau of Industrial Housing and Transportation. It was authorized to provide housing for workers and families in arsenals, Navy yards and other defense industries. The US Housing Corporation could make loans to builders, but generally it built housing itself. By the fall of 1919, whole communities had been built by the federal government in an unprecedented period. At Quincy, Massachusetts three developments were built by the USHC all designed by James E. McLaughlin to house workers employed at the vast Fore River Shipyard Company owned by Bethlehem Steel. Overnight, wrote Stanley Taylor in the December,1918 issue of American Architect, “ the greatest single owner of workingmen’s houses in America was the United States government.” In all, 27 developments were built in 16 states for a total cost of $52. 3 million. In 1933, Ernest M. Fisher wrote that the “ greatest single contribution of the USHC was the advantages shown by the correlation in a single enterprise of all factors put in place to build housing. Operating on a large scale, city planner, architect, engineer and builder all put together as a single result attractive and unified housing.” ( Quoted in Robert Moore Fisher, 20 Years of Public Housing, 1959 ). It would be a rehearsal for the housing programs of the New Deal.

The Hoover administration would follow the precedent established by the Emergency Fleet Corporation, but Congress couldn’t scrap it fast enough after WW I. The 1921 Report to the Senate Select Committee on Reconstruction flatly stated that “ it is in the interest of the public welfare that the federal, state and municipal governments should not participate directly in the housing business.” All EFC housing were sold at a loss of $26 million. ( In the spring of 1921, the Quincy houses were sold at auction for 40% less than the cost to build them. Advertisement, Boston Herald. May 22,1921. )

The Roosevelt Administration confronted the housing crisis in two ways: the first as a public works program and the second as permanent public policy.

On June 16, 1933, President Roosevelt signed into law the National Industrial Recovery Act ( NIRA) to be directed by the Secretary of the Interior, Harold L. Ickes. ( 40 Stat. 195. 1933 ). Title II of the Act authorized a comprehensive program of public works including low cost housing and slum clearance. Ickes organized the Housing Division to implement Title II. Beginning in February of 1934, the Housing Division designed, financed and built 51 developments across the country. This provided direct employment nationwide to 230 architects, 45 landscape architects and 100,000 masons, carpenters, bricklayers, iron workers, truck drivers and railroad freight handlers. Two of these were in Massachusetts: Old Harbor Village in South Boston and New Towne Court in East Cambridge. New Towne Court, just outside Kendall Square, began receiving families in January of 1938. Opening day at Old Harbor, now called Mary Ellen McCormack Houses, was on May 1,1938. In his first Report to the President, Ickes stated that the Housing Division had five goals, one of which was “ to demonstrae to private builders and planners and the public at large the practicality of large scale community planning.”

South Boston was selected as the site for Boston’s first public housing development because of the persuasiveness of Congressman John W. McCormack, born and raised in Andrew Square ( the development is today named for the Congressman’s mother). Old Harbor was built on 26 acres of vacant land ( some of it unfilled saltmarsh ) close to Andrew Square between Dorchester and Old Colony Avenues directly opposite Columbus Park. Construction of Old Harbor received a setback in July of 1935 . Large real estate interests took the Housing Division to court in order to block eminent domain proceedings. The U.S.6th Circuit Court of Appeal ruled that the government could not take land by eminent domain for federal housing. This was a right reserved to the states and local housing authorities needed be established to acquire land for public housing. “ Buying one person’s property and selling it or leasing it to another,” the court said, “ is not within the scope of power of the federal government… [ The NIRA ] is at the unfettered discretion of the president [ which is ] an illegal delegation of legislative authority.” The Circuit Court further stated that eminent domain cannot be exercised by the federal government only for a select group - in this case low income people; only the states had this authority.

The Commonwealth passed legislation authorizing public housing authorities on July 26 ,1935 ( MGL Chpt 449 Acts of 1935). The City Council approved the Boston Housing Authority on October 1, 1935. The construction of Old Harbor Village was not stopped by the 6th Circuit Court ruling because the development was built on vacant land. About 20 parcels of land was acquired between September and October 1935 at a cost to the Housing Division of $520,079.

Another delay was caused when the City Council and Mayor Frederick Mansfield unsuccessfully argued that the federal government had to pay property taxes on the development.

Since the Public Works Administration was essentially established to provide jobs, the design of Old Harbor was spread out among seventeen associated architects with Joseph Leland as Chief Architect. Plans were approved in March of 1936 for nineteen walk up apartments from three to five stories high; fifteen, two story row houses, an administration building, power plant and maintenance building. The row houses were the only ones built in any Boston public housing development. There were 1016 apartments of 3 to 5 rooms. The total cost of design and construction was $5. 8 million. Plans and photographs of the nearly completed development were published in Architectural Forum for May, 1938.

Old Harbor was the first housing in Boston inspired by modern European design for domestic architecture that had inspired young architects and city planners in the 1920’s. The Museum of Modern Art in New York City held the first exhibit on this style from February 2 to March 30, 1932. The style was the model for Heath Street and every other housing development in Boston. Briefly. it was marked by functional brick boxes in T, U , L or X shape set out in geometric superblocks without regard to city street patterns. The superblocks created open spaces between them for playgrounds, drying yards and a large community common or square. They were the common grounds of Woodbourne magnified one hundred times. Old Harbor has only one through street , and that is on its edge. The other streets are narrow curving ways designed only for residents.

Old Harbor was built on vacant land so there was no relocation process of finding homes for those displaced by the development as at Heath Street. The Boston Housing Authority managed the rental process. Apartments were made available to any Boston resident except, ironically, those on relief or on the Public Works Administration payroll. Rents were set by the BHA with Housing Division approval: a 3 room apartment rented for $22.15 a month and a 5 room flat for $31. 90. This was out of the price range of most tenement residents. The average annual salary of a tenement working man in 1933 was $1290. In 1935, 56% of all New England families not on relief earned no more than $1500 a year. This meant that a three room apartment would take up 1/4 of the annual take home pay.

A lease agreement to manage Old harbor Village was signed between the USHA and the BHA on Feb. 18 ,1938. The BHA was swamped with 7500 applications from which they selected 557. Many of them had never lived in an apartment with central heating, hot water and flush toilets much less a laundry room in the basement. Ten thousand people attended the dedication on September 11,1938 ; it made the front page of the Boston Globe.

In one of the first critiques of public housing, real estate editor F. E. Drew of the Boston Herald wrote cautiously on October 9, 1938, “ The federal housing projects are still debatable as to both social benefit and financial injury to apartment house men. Many owners have lost tenants … time and experience in the next few years will tell more of the story.”

Housing built directly by the federal government ended in 1935 when the NIRA was declared unconstitutional by the U S Supreme Court. Old Harbor Village and New Towne Court - both underway in 1935 - would be completed, but the housing crisis facing Boston now awaited Congressional action.

Advocates for well-built, low cost housing for the working man were not satisfied with the Housing Division because it was a public works program, not a housing program. They also criticized the Division for building new housing on vacant land, such as at Old Harbor, than in razing dilapidated slums for better housing ( such as New Towne Court ). To the housing advocates of the 1930’s. a half century of failed attempts by philanthropic housing reformers was evidence enough that only government would ever be able to solve the problem of affordable housing. In 1934, one of the preeminent leaders of housing reform in 1930’s America published an influential book called simply Modern Housing. “ The fundamental premise about housing has undergone a tremendous change ,” Catherine Bauer wrote “ It has become a public utility. The right to live in a decent dwelling has taken its place among the national rights, such as water, sanitation, fire and police protection. The solution has nothing to do with the real estate industry. The old real estate industry is largely responsible for the bad conditions of cities and the existence of a housing problem.” Bauer and her housing reform colleagues wanted a permanent public housing policy and they turned to one of the titans of the New Deal, Senator Robert F. Wagner, of New York to get it.

In January of 1935, Senator Wagner introduced the first long range housing act in the nation’s history. It would leave construction and management to local authorities and administration and financing to a new federal housing agency. Catherine Bauer was one of its main authors.

But as Robert Moore Fisher points out in his book Twenty Years of Public Housing, Congress would not have entertained such revolutionary legislation if they had first not seen what public investment in housing looked like. The 1933 - 1935 PWA housing program, wrote Fisher, “gave a practical and legal background for a permanent federal housing program. First, it helped focus public attention to the problem of substandard housing and the use of federal funds to accomplish that. Second, it built the first low rent housing developments in the nation for the public to see. And finally, it stimulated the creation of 30 public housing authorities by 1937.” Public housing went straight to the heart of private property rights, a major pillar of American life. Common land was not a popular notion. Opposition from the National Association of Real Estate Boards, rural congressmen and anti New Deal Republicans was stiff and the bill failed to pass for two years. Another reason was that President Roosevelt did not put his formidable political weight behind the bill.

His cousin, President Theodore Roosevelt was a champion of Progressive legislation yet despite appointing an advisory committee on slums in 1908, he, like most Progressives, took no further action. Its report to the 60th Congress was too far ahead of its time: It stated that it was only common sense that government should provide decent dwellings if it can build prisons for the criminals, asylums for the afflicted and public schools and libraries.

Senator Wagner repeated this new role for Government in a nationwide radio address in April of 1936, “ [ The Housing Bill ] embodies recognition on the part of a socially awakened people that the distribution of our national income has not been entirely equitable and that partially subsidized houisng. like free schools, free roads and free parks is the next step that we must take to forge a new order.”

Franklin Roosevelt was faced with a national emergency and on October 28, 1936 in one of his first public statements on housing, he made it plain that - like the 1908 Report - the federal government had a responsibility to provide better housing for the poor citizens of America. In a speech in Senator Wagner ’s district, of New York City, the President said “We have for too long neglected the housing problem for all our lower income groups. We have spent large sums of money on parks. on highways. on bridges and museums … but we have not yet begun to spend money to help the families in the overcrowded sections of our cities to live as American citizens have a right to live. We need action to get better housing. Senator Wagner and I had hoped for a new law at the last session of Congress … I am confident that the next Congress will start us on the way with a sound housing policy.”

In his annual message to Congress on January 6, 1937, President Roosevelt spoke again about housing. “ There are far reaching problems still with us for which democracy must find solutions… for example many millions of American still live in habitations which not only fail to provide the physical benefits of modern civilization, but breed disease and impair the health of future generations. The menace exists not only in slum areas of very large cities but smaller cities as well.” This was crystallized in one of the most famous statements of his presidency. In his second inaugural address on January 20, 1937 he said :

“I see one third of a nation ill housed, ill clad and ill nourished.”

Senator Wagner introduced a revised housing bill ( S 1685 ) on February 24,1937. Democratic Representative Henry Steagall of Alabama introduced an identical bill in the House ( H 1544). No great partisan of public housing , the chairman of the Banking and Currency Committee was nevertheless loyal to the President and when Roosevelt came out in favor of a housing bill, Steagall took it as marching orders.

As others have said before, what contributed most to form the Wagner - Steagall Act was not its substance but concessions made to appease its opponents. During debate on the bill in August, two amendments were offered up. Massachusetts Senator David I Walsh introduced a measure which stated that one new housing unit had to be built for every one razed in slum clearance. Walsh was no supporter of public housing; he believed it was a misuse of government funds and in direct competition with private industry. He also believed that it wasn’t serving the poor and he justifiably pointed to the rent structure at Old Harbor as evidence.

The most far reaching and dangerous amendment was proposed by Senator Harry F. Byrd of Virginia on August 4,1937. Byrd believed that radical social philosophies motivated many of the public works projects of the New Deal and wasted millions of dollars. The Byrd Amendment placed a construction cap limit in the housing bill of $4000 for a 4 room unit or $1000 per room. In conference committee , the Byrd Amendment was revised to read that for any city with a population over 500,000 ( such as Boston whose population in 1938 was over 800,000) the cap on apartment costs would be $1250 per room not to exceed $5000; in all other cities the $1000 per room cost restriction remained. The Heath Street Development was designed and built as it was because of Byrd’s unrealistic cost restrictions on each apartment.

In response to the Byrd amendment, Congressman John O’Connor of New York city said in the House chamber on August 18, 1937 that “You cannot possibly in any of the metropolitan districts build one of these projects at a cost of $1000 a room or $4000 a unit. The two [ PWA ] projects in New York, the Harlem and the Williamsburg, cost $1600 a room. Of all the items in the bill, this is the most important. You might as well forget about a housing bill if you adapt an amendment [ of a ] limitation of $4000 a unit. It just cannot be done.”

But Frank Hancock, Congressman from North Carolina, thought about the morale of those who owned their own homes “ through self denial, frugality and self discipline. How do you reckon they will feel when they see this special class entering these comparatively luxurious apartments? The projects built by PWA are superior to the home of the average family. Fellows, let us watch our step, for God knows we are in dangerous territory. Do not do this thing.”

Congressman McCormack said that the real reason for so much emotional opposition to the bill was “unjustified fear”. This was humanitarian legislation and “ we should not permit this feeling to prevent its passage”.

The Wagner- Steagall Act passed the Senate on August 6, 1937 by a vote of 40 to 39. The two Massachusetts senators were divided in their votes: Senator Henry Cabot Lodge supported the bill while Senator Martin Walsh voted no. The House took up the bill on August 18,1937 with 275 members approving public housing and 86 against. There were 14 congressman from Massachusetts in the 75th Congress and all but only two voted in favor of the bill, John McCormack and Joseph E Casey of Clinton. Congressmen representing working class cities such as Lynn, Somerville and Worcester all opposed the housing act including Representative Edith Nourse Rogers of the mill city of Lowell. ( In December of 1937 Lowell was designated as eligible for $2 .7 million in housing funds under the Wagner- Steagall Act ). In the May, 1938 issue of Architectural Forum, the editors wrote . “ For this country to approve the Wagner- Steagall Act is no mean feat… . [ the act ] approaches housing not as employment or a recovery measure but as housing. Congress has been educated to a new approach to housing as a perpetual social obligation ( emphasis added ).”

(On January 18, 1938, The Federal Theater Project opened its new play “ One Third of a Nation” in New York. It was reviewed with photographs from the production in the February issue of Architectural Forum. It was still playing to packed houses when the Forum reported in its May. 1938 issue that the play is “ not without a certain fortuitous significance since the star of the piece is not a blonde but Housing. Housing has just reached its political majority with the passage of the Wagner Steagall Act.” ).

President Roosevelt signed the Wagner-Steagall Housing Act into law on Sept. 1,1937 ( 50 Stat. 888 1937). Its preamble stated “It is hereby the policy of the United States to assist the several states to alleviate unsafe and unsanitary housing conditions and the acute shortage of decent,safe and sanitary dwellings for families of low income.” The bill established the United States Housing Authority ( USHA ), which is today known as the Department of Housing and Urban Development. The USHA was authorized to enter into 60 year loan agreements with local housing authorities for 90% of the cost of housing developments. The first appropriation was $800 million; a second appropriation of $800 million, under which Heath Street was built, was authorized by Congress with little commotion in the summer of 1938. After a glimmer of hope in 1937, the Depression darkened the country in 1938 and Congress wanted to revive the economy.

The Boston Housing Authority Board held a lengthy discussion of the provisions of the Wagner act at its September 15,1937 meeting. In December of 1937, Lowell and Boston had been notified by the US Housing Authority ( USHA ) that they had been approved for housing funds. Boston was eligible for $9 million in housing funds and in that same month, Mayor Mansfield made a tentative agreement with the USHA for three developments: Charlestown, East Boston and South Boston .

But Boston could not receive those funds until the Massachusetts Housing Act was amended to comply with the Wagner - Steagall bill.

Governor Charles Hurley appointed Christian Herter to chair a committee charged with amending the Massachusetts Housing Act.

The BHA had to be given authorization to:

Enter into agreements with federal agencies relative to borrowing funds.

Enter into a contract with the federal government to purchase or lease housing which it owned. This referred specifically to the Old Harbor Village which was owned by the United States. It would not be transferred to the BHA until December 31,1958 ).

Determine the amount of money to be paid to the city annually in lieu of property taxes. Real estate owned by a housing authority was deemed public property and exempt from taxation.

After the City Council approved the creation of the Boston Housing Authority, Mayor Frederick Mansfield appointed architect George Nelson Jacobs as chairman of the six member authority. The other members were architect Harold Field Kellogg, George Green, hotel manger Bradbury F. Cushing, John Carroll, chairman of the State Housing Authority, and Reverend Thomas R. Reynolds, pastor of St. Matthews Church in Dorchester. ( The latter two were appointed by the Commonwealth). In January of 1938, Mansfield’s successor, Maurice Tobin replaced Jacobs with 33 year old John A. Breen, vice president of the Massachusetts Real Estate Exchange. These were the men who would change the housing landscape of Boston.

Debate on a new Massachusetts Housing bill ( H 1965 ) raged for seven months throughout 1938. One of the first meetings took place before the Massachusetts Real Estate Owners Association on February 17,1938. Robert Gardner Wilson, Republican of Ward 17 in Dorchester, said that “ the Old Harbor project is in direct competition with private home owners and no private home owner can compete with them … it’s really not American. We must fight the socialistic policies of the New Deal.” Wilson, who in 1938 had served for 11 years on the Council, would be a vociferous critic of public housing for years. His district, ironically, included St. Matthew’s parish outside Codman Square , the church of BHA member Rev. Reynolds.

Gardner’s opposite was Councilor Clement A. Norton, of Ward 18 which included all of Mattapan and Hyde Park. He characterized himself as the “ friend of the Housing Authority and a believer in what the Authority is doing.” Norton testified at the February hearing that “ private building has admitted its inability to take care of the lowest one third income class. Government must … come to their rescue. Whether we like it or not, slum clearance is here to stay.”

“Bitter protests by property owners,” shouted the headline of the Evening Globe of June 6,1938 reporting on a public hearing on H1965. “ Leading the assault was Mrs. Hannah Connors, president of the Real Estate Owners Association: ‘Federal housing is paving the way for the advance of Communism in this country.’”

Governor Hurley signed the Massachusetts Housing Authority Act into law on July 5, 1938 ( MGL Chpt 484 Acts of 1938 ). His remarks at the State House made little reference to housing for low income families; rather he stressed that the legislation would increase employment for the construction trades. By then the amount of funding available for Boston public housing had increased to $31 million and two weeks later USHA officials came to the city to present Mayor Tobin with the first $15 million in loan guarantees. They also conferred with him on proposed sites which had to meet certain guidelines of the USHA Acquisition Department. Councilor Wilson said in the Globe on July 16,1938 in response to the visit by the USHA that “ no new federal housing should be built until Old Harbor Village is studied to determine whether real estate owners are being penalized with free real estate built with federal funds.”

In August, the BHA began to prepare a 15 year bond issue to cover the 10% of the costs of housing for which it was responsible. Under State law , savings banks could not invest in BHA bonds, but all other banks and financial institutions were invited to participate. On November 29,1940, as the Heath Street Development was getting underway, the BHA entered into a restructured loan contract with the USHA at an interest rate of 2.5%.

In the areas targeted for public housing, the BHA surveyed the existing conditions. What we consider automatic in the way we live today was not the case for many Bostonians in 1938: 92 % of the dwelling places had no central heating, 47% had no hot water and 20% had no bathrooms in the unit but shared communal toilets. To reduce its costs , the BHA narrowed its site selection to land already owned by the City of Boston or in tax foreclosure by the City. Of the land acquired for the first 4 developments, 23% was city owned. On October 24, 1938, the City Council approved ( 17 to 3 ) a service contract between the BHA and the City of Boston for 4 housing sites: Charlestown ( Bunker Hill ), South Boston ( Old Colony ), Roxbury ( Mission Hill ) and Lower Roxbury ( Lenox Street ). The Globe reported that before the vote, “ an avalanche of letters and telegrams descended on the 21 member council” for and against the contract. Labor was strongly in favor, and the building trades representative wrote the council that “the projects will employ thousands of men not on WPA payrolls.”

In an effort to stop the spread of further public housing developments, a non binding referendum was held in 4 wards in November, 1938. Ward 12 ( Roxbury : Dudley Square to Franklin Park ), Ward 18 represented by Clement Norton, Ward 19 ( Jamaica Plain : Forest Hills to Egleston Square ), and Ward 20, West Roxbury. The vote was 30,685 opposed to 14,170 in favor of public housing in these districts. As the BHA was taking land necessary to build the first 4 developments, Councilor Gardner stood up in Council meeting and asked that Mayor Tobin hold a city wide binding plebiscite on public housing before the BHA submits its ten year plan for housing 35,000 families. Based on the November vote , he said, “ I know that the people of Boston are at least two to one” against public housing.

Yet public housing was now on the verge of becoming part of Boston’s architectural heritage . On the opposite slope of Parker Hill from Heath Street, the Lenox Street development got underway in the summer of 1939. In July, the BHA took 4 takings of land covering 5.75 acres between Smith, Ward and Parker Streets. In the next few months, 742 run-down tenements were razed. The architect George Ernest Robinson designed a series of 13 buildings opposite Smith Playground. Construction began on November 9, 1939 and it opened in the spring of 1941.

In April of 1939, the BHA selected 4 other sites for public housing: Roxbury ( Orchard Park ), South End ( Cathedral ), East Boston ( Maverick ), and Heath Street in Jamaica Plain. The Heath Street site ( numbered Mass. 2-7 ) was bordered by Heath Street, a main east- west thoroughfare ; and Bickford and Walden Streets. The Plant Shoe Factory property formed the back of the development. The location was selected for 5 main reasons:

It was a deteriorating area which was rapidly spreading its blight.

The land could be purchased for $1.50 a square foot as mandated by the USHA.

It was convenient to street car, train and bus transportation.

Streets could be closed within the boundaries which allowed for good planning of the site.

Relocation of current residents presented no problems.

The site for the Heath Street Development was over ten acres of level ground in a valley below Parker Hill. In the 17th century, the land was a pasture belonging to the family of the Revolutionary War General William Heath. After the general’s death in 1814, it was bequeathed to his sons. Beginning in 1860, Mary Heath, the widow of Joseph Heath began to sell the farm off in parcels. Sixty-five multi family and single family wooden houses had been built by 1873 as well as a leather factory on what became Minden Street when it was laid out in 1879. This represented half of the housing stock in place when the land was acquired by the BHA in 1940.

This site was located in Census Tract V- 6 which stretched from Heath Street to Day Street. In 1935 the population was 1,290, all of whom were white. There were 621 buildings that included 1,459 dwelling units. Over 1000 apartments had no central heating; the only source of heat was the kitchen stove.

It was in the factory district of Jamaica Plain: the Plant Shoe Factory on Centre Street, Chelmsford Ginger Ale Company on Heath Street and the Moxie Bottling Company on Bickford Street as well as four other breweries or bottling plants were within a few minutes walk. It was convenient to different modes of transportation: the Heath Street station of the Boston and Provident Railroad was a quarter mile away as were the Columbus Avenue street cars; the Centre Street bus lines were close to many homes. Also close by were Blessed Sacrament Church, the Jefferson , Mozart and Bulfinch Schools and McLaughlin Playground.

The community was largely Italian - Americans who worked as stitchers in the shoe factory or repairing harnesses at the bottling plants. ( A reminder of that community can be seen at the intersection of Chestnut Avenue and Centre Street which named in honor of Captain Peter R. Mutascio ). There was also a small group of German Jews who worked in the breweries.

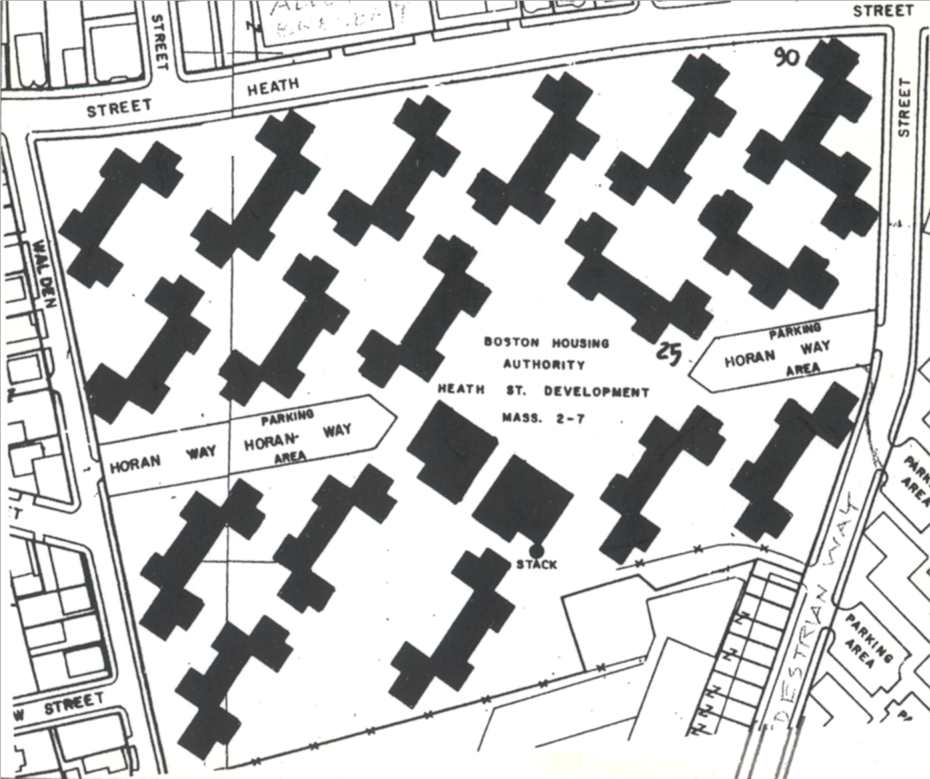

The BHA Board approved the site on February 23, 1939 . It was conveniently located between two through streets, Walden and Bickford, which connected Heath Street to Centre Street. Based on the terms of conditions of the Contract signed between the BHA and the USHA on March 10, 1938 outlining the arrangement by which the two parties would finance and build public housing developments in Boston, the housing to be built on Heath Street would not be named for any living person. The development was simply named for the very familiar street which formed the main entrance to the apartments. ( To the USHA it was called - and still is to this day to its successor agency the Department of Housing and Urban Development - as Mass 2-7 ).

Bonds worth $14, 082,000 were authorized by the USHA to be sold for the construction of five developments: Orchard Park in Roxbury, Lenox Street in Lower Roxbury, Heath Street, Maverick in East Boston and Cathedral in the South End. ( The coming of war postponed the Cathedral housing until after 1945 ). Each development had accounts in separate banks approved the USHA in which were deposited the proceeds from the sale of the bonds and drawn down for surveys, engineering, design, demolition and construction costs. On January 3, 1940, a Development Fund Agreement was established for Heath Street at the Webster and Atlas National Bank located in the Sears Building at 199 Washington Street ( One Boston Place occupies the site today ).

Henry F. Bryant and Son was awarded a $2,885 contract to survey the site on March 13, 1940. Robert T. Fowler of Jamaica Plain was one of four appraisers of the properties to be acquired. Rehousing of families living on the site took place between September and November.

Most of the land taking for Mass. 2-7 was completed on July 30, 1940; six city owned parcels - taken previously for non payment of taxes - were sold to the BHA on October 8, 1940. In total, 116 parcels of land were acquired by eminent domain at a cost of $ 497,000 . One building was the original Jefferson School built by the then City of Roxbury at the corner of Walden and Heath Street, which at the time of purchase by the BHA was being used as a motor vehicle repair shop. The demolition contract was awarded in February of 1941. A total of 115 buildings were torn down including garages, stables and not a few outhouses. Many of the buildings were dilapidated and some were so unsafe that the BHA had them razed as soon as they were bought. Six interior streets were discontinued and graded flat to make a roughly square lot : Arklow, Ulmer, Posen and Minden Streets, Heath Place and Heath Avenue. Horan Way was laid out through the development along the same line of Minden Street.

All architects selected by the BHA were given final approval by the USHA based on their guidelines and fee structures, not by the lowest bid, as demanded by the Boston City Council. M. A. Dyer was chosen as the architect for Heath Street Development on July 10, 1940.

Michael Andrew Dyer ( 1886 - 1954 ) was born in Malden to Irish immigrant parents. His father, Michael Sr. was a carpenter who soon moved the family to Medford; in 1888 he was listed in the Malden city directory as a carpenter- contractor. Young Michael graduated from Medford High School and then took classes at MIT; he did not receive a degree. He joined his father’s contracting business at 26 Court Street in Malden in 1907 where he worked as an architect until he opened his own firm in 1924.

The Boston architect Robert Neiley worked as a young g draftsman for MA Dyer Associates in 1950 and he described Michael Dyer as “a real architect in the old sense; he had good traditional training and knew what makes a good building.”

As a young apprentice, Dyer began his profession in the building trade working with his father, so he knew materials and construction before he knew design. Unlike most of today’s architects who don’t learn plastering, framing or bricklaying, Dyer learned that as a teenager by doing. The most famous Renaissance architect of them all, Andrea Palladio was a stonemason by trade and like him, Dyer was a tradesman first. More than likely he worked with his father in designing and building apartment houses and single family homes in the railroad suburbs of Malden, Medford and Woburn. When he opened his own practice, his work shifted to almost excusively public commissions. In 1931, he was the architect of the Woburn Town Hall and in 1937, his firm designed the Medford City Hall, his home town ( He spoke at the dedication ceremony ).

The Heath Street development design contract was probably his first Boston job, but it was not his last: he would work in Boston for the rest of his career. M. A. Dyer Architects designed four more Boston public housing developments between 1949 and 1954 including the massive Columbia Point apartments in Dorchester ( today known as Harbor Point ). In 1952, he designed the BHA central administration building on Kemp Street in South Boston ( adjacent to Old Harbor ) and in 1954, MA Dyer designed the Lemuel Shattuck Hospital in Jamaica Plain.

All of his skills as a builder were required to design the Heath Street Houses where the plans and specifications were controlled by the cost restrictions of the Byrd Amendment. The Wagner - Steagall Act emphasized this and also tried to calm the real estate industry in the preamble: “ Such projects will not be of elaborate or expensive design or materials and economy will be promoted both in construction and administration and the average construction cost is not to be greater than the average cost of dwelling units currently produced by the private sector.”

Plans were completed in three months and building permits were approved on March 1, 1941 for 17 apartment blocks which contained 24 apartments each for a total of 420 residences, an administration building and social hall. Construction began soon afterwards. The largest apartment building was Building Number Ten ( 90 - 98 Heath Street at the corner of Bickford Street ) which had 36 apartments. Most of the apartment blocks were of the same dimensions; Building Number One ( 170 Heath Street ) at the corner of Heath and Walden Streets was 158 feet long, 69 feet wide and 110 feet high. The load bearing walls were built of brick with concrete block back up. Number 170 Heath Street had six , 3 and 1/2 room; nine, 5 and 1/2 room and nine, 4 and 1/2 room apartments. A typical bedroom measured 8 feet 9 inches by 14 feet ten inches and a kitchen averaged 9 feet by 10 feet. Most of the apartments at Heath Street ( 186 out of 420 ) had 4 and 1/2 rooms.

The apartment blocks included courtyards designed for drying yards. play areas and sitting spaces. The community building, administration office , power plant and maintenance shop faced out onto grassed play area for games and for public events. A second open space for sitting and gardens was provided behind the community/ maintenance building. There was no vehicular streets; the circulation patterns were built for pedestrians only. Two perpendicular parking lots named Horan Way were built from Bickford Street and Walden Street and dead ended at the playground. Horan Way was the principle interior thoroughfare, but it was for pedestrians only. All service vehicles entered the development from a separate road from Bickford Street over an easement granted by the Plant Shoe Factory to the maintenance building.

The BHA Board selected Hallam L. Movius, ASLA, as landscape architect and site planner for Heath Street on July 11,1940. Movius, whose office was located at 115 Newbury Street, was also responsible for the site planning and landscaping of Orchard Park, which was planned and built concurrently with Heath Street. These were the last two works Movius designed; he died on August 1, 1942 at the age of 61.

Born in Buffalo, New York, Movius spent three years at the Harvard Graduate school of Landscape Architecture after receiving his BA from the Harvard University in 1902. He was an apprentice with the landscape architect Arthur Shurcliff in 1905 and then worked with several architectural firms before opening his own office in 1912. ( His partner was the architect Arthur G. Rotch ).

His professional work extended from cemeteries to housing subdivisions, but his largest commissions were campus designs for the University of Buffalo and Bowdoin College in Maine. The experience Movius had with large scale campus planning as well as his early work on the staff of architectural firms, served him well in collaborating with Dyer at Heath Street and the architect John M Gray at Orchard Park.

The phenomenon of the landscaping of public housing developments was very new to the profession, however. At the 41st annual meeting of the American Society of Landscape Architects ( ASLA ) held at Washington DC in January of 1940 a full roundtable discussion was devoted to “ Landscape Design and Low Rent Housing” ( See Landscape Architecture, April, 1940, page 132 ). The meeting opened with the admission that “ many landscape architects have had apparent difficulty in solving the planting problems on housing projects.”

An official from the USHA said that in earning how to tackle the job of low rent housing, the landscape architect has to remember two basic points:

The first was that large scale public housing programs required the integration of architect, landscape architect and engineer.

The second was that every project must be “orderly, dignified, livable and very inexpensive.”

Two problems that the landscape architect needed to solve in planning public housing was the matter of different surface treatments; playgrounds, roadways courtyards and common spaces required different surface materials whether it was gravel, macadam , paving blocks or grass.

The second was the ingenuity in the selection of plant materials that are inexpensive and hardy. “ There has still to be produced the housing project having a site developed only with trees and relatively indestructible smaller plants or perhaps with only trees for plant materials.”

Dyer and Movius worked as a team for over three months to produce a plan in which housing and open spaces were balanced in a harmonious pattern. each building, except for those at the corners, had its own drying yard for washing, sitting area and play area. The buildings were grouped together so that the wings would create geometrical squares. In each square shape, Movius placed the play areas and drying yards. Sitting areas were tucked inside the two corner entrances of each building. All of these spaces had hard surfaces, but where the drying yards and play spaces were made of bituminous, the sitting areas were surfaced with paving blocks. There were two large common spaces which the BHA intended for the community as a whole, not as a private reserve for the residents of the development. In the center of the site plan was a one half acre play area with a spray pool ( probably the first spray pool in Jamaica Plain ). This was located adjacent to and served as an outdoor room for the social hall. A second common space was a 550 foot long shady mall called Plant Court which extended between the rear of the social hall and maintenance building to the west property line of the Plant Shoe Factory. Buildings number 14, 15 and 16 look out over this green.

Movius was careful to plant a green edge of grass around the outside of the development, particularly the Heath and Walden Street borders. The two corner buildings at Heath - Bickford and Heath - Walden, as well as Building 17 ( 42 Walden Street at the corner of Horan Way ) have the most lawn areas.

The planting plan was a rich mixture of trees, shrubs and vines. Foundation plantings were kept to a minimum and vines were planted on the fences of the drying yards and play areas outside each apartment. At Building Number One, clematis vines were planted around the drying yard fence. Berberry, mulberry, honeysuckle and privet shrubs were planted at the corners of the building; to provide a little privacy, the sitting areas were screened with privet hedge also.

Eight different varieties of trees were planted throughout the development including linden. American elm,plane tree. little leaf hawthorn and ailanthus. At building number one, mulberry, thornless honey locust and Norway maples were planted ( several of the latter are still providing shade to that corner building today ).

The John Bowen Company was selected as the contractor on December 4, 1940 with a bid of $1.6 million. ( Bowen built the Bunker Hill and Maverick developments before the war and Franklin Hill in 1951 - 52 ). Demolition was well underway when John Breen, the Chairman of the BHA, escorted Governor Leverett Saltonstall, Mayor Maurice Tobin and the State Housing Board on a tour of the eight developments under construction or nearly completed on January 24, 1941.

The original purpose of public housing began to change, however, in 1941. On May 27, 1941, in reaction to the war in Europe, President Roosevelt announced that an unlimited national emergency confronted the United States. The pace of war - related industry, from ships to ammunition - increased dramatically and as employment rose so did the need for housing of defense workers. Unlike 1917, however, the United States already had housing under construction in the form of low rent apartments nationwide. ( By the end of 1941, 143,200 housing units had been built across the country ). To house shipyard workers, the barely completed Old Colony Development in South Boston, located within sight of Old Harbor Village, was sold by the BHA to the federal government in February of 1941 for $21,530,000 ( Authorized by the Lanham Act. PL 849. 76th Congress). On November 4, 1941, when Heath Street was over half built, the BHA adapted a resolution that gave preferential housing to low income defense workers at Heath Street and Maverick Street developments. ( Low income was defined as having an annual wage of $1768 or less ). After the declaration of war a month later, apartments in all the new developments were offered first to defense workers eligible under the income limits.

On January 6, 1942, the Chief of Construction of the BHA accepted as completed buildings number one through five and buildings seven and seventeen. Three weeks later the whole development was accepted as completed.

Rents for the Heath Street development were established on January 6, 1942:

As mandated by the Wagner Steagall Act, no family would be accepted whose annual income was in excess of five times the annual rent. On April 1, 1942, the BHA increased the income level to $2800 for defense workers.

A four bedroom apartment plus utilities rented at $18 a month for a family whose annual income did not exceed $918.

For a family with an income of $2596, the rent was $45 for a four rooms apartment.

Income was one standard for judging the eligibility of tenants, another was if a family had been living for six months or longer in a substandard apartment or house. Substandard was defined as:

Hazardous; in need of roof, wall, steps or floor repairs.

No inside toilets.

No electricity.

No running water.

One or more families living in the same unit.

During January of 1942, 106 leases were completed and the first tenants began taking their apartments the next month. Heath street Houses was fully occupied by November. Many of the tenants were families of active duty Naval personnel as well as defense workers. (After the war, Heath Street became housing for returning servicemen and their young families.) Some families at their request were transferred to heath street from Old Harbor because they need a five room apartment.

Final certificate of title was taken by the BHA on November 25, 1942. The Heath Street Development cost $2,436,000 to design and build.

The Heath Street Development solved the two most critical problems of previous philanthropic housing in Boston: how to build big enough and with enough financing to keep costs down and rents affordable for the poor. Despite sound planning and good intentions, every philanthropic housing programs since the first one in 1871 had floundered on these two problems which meant that for the most part the housing built was out of reach of the working poor. Only the United States government had enough capital and resources to lower the costs of housing.

Most importantly of all, Heath Street was the first self contained community Jamaica Plain had ever seen. In keeping with one of the main ideologies of housing reformers of the New Deal Era, public housing was developed as a planned community. Woodbourne came close with common areas for gardens and playgrounds and a community building; but Heath Street was an orderly community with spaces individually adapted for specific uses. It had its own heating plant, maintenance facility, management office, community rooms, playground as well as play spaces in front of the apartment door, sitting areas and a small town common for gardens and more passive use at the rear of the development. Parking areas and pedestrian walkways were clearly separated; for mothers with children it was one of the safest places to live in Jamaica Plain because there was no motor vehicle traffic in front of any building.

As architecture, Heath Street is also unique because its site planning and architectural style were unknown before 1938. The housing reformers and city planners of the New Deal Era championed not only low income housing but an egalitarian architectural style of pure function devoid of any historical references, such as the English cottage and Colonial Revival at Woodbourne, the last of the philanthropic housing. Heath Street Houses was a mixture of the American garden city, Beaux Arts planning and European innovation.

In Modern Housing, Catherine Bauer explained that “ old methods must be considered outmoded and new ones set in their place. She advocated for self contained residential neighborhood with a central plant for heat and hot water

Prior to 1938 when Old Harbor opened, the only precedents for government sponsored housing was in Europe and in the 1920’s idealistic architects an city planners flocked to Germany, Holland. Switzerland and France to see what the future of housing looked like.

“There are certain times,” wrote the architectural historian Henry Russell Hitchcock in 1932,” When a new [architecture ] really begins” In America that time was between 1932 and 1934 when European models of cluster housing was mixed with the International Style to become modern housing.

The Heath Street Houses followed the style of the Zeilenbau formation of standardized rows oriented north - south for maximum morning and afternoon light. As shown at Heath Street, these rows were set in rows on a northeast to southeast axis at an angle to the main street. This pattern of housing began to be built in Munich and Berlin just before WW I and picked up again in other German cities in the 1920’s. Its basic characteristic was that of large but low scale three to four story walk up buildings set in wide open usually level sites in which the old street patterns had been destroyed for a free form space. By breaking away from the usually disorganized, often narrow street pattern, city planners were free to place buildings in less cramped spaces to make allowances for light, ventilation, public spaces and playgrounds.

Heath Street Houses was laid out in alternating U shaped blocks set at 60 degree angles to Heath and Walden Streets. The apartment blocks are spaced out to create five interior courts. Unlike the surrounding housing, the Heath Street apartments relate to each other as a whole rather to the city street. This concept fit perfectly into the ideology of the housing reformers of the time who wanted housing styles and site patterns that looked completely different from the old slum tenement streets. The three story buildings of Heath Street fit into the low scale residential housing patterns of the rest of the neighborhood, but otherwise it was a completely new town.

In Boston the Zeilenbau style was mixed with the familiar Garden City plan of which Woodbourne is the best example. The Heath Street apartment houses were ( and still are) nestled among tree shaded green lawns, courtyards and playgrounds. ( the plaza has since been taken up for parking ). This is classic Garden City planning but the architecture went out of its way to be unapoligetically functional. Heath Street was built in the International Style which America glimpsed for the first time in 1932 at the Museum of Modern Art, exhibit organized by Henry Russell Hitchcock and Phillip Johnson. To accompany the displays, Hitchcock wrote one of the first descriptions in America of this new European architecture.

The International Style had no history. It was not based on Greek temples. French chateaux, Italian palaces or Japanese pagodas. It was an architecture, wrote Hitchcock, based on economics not aesthetics.

“Modern construction is one of straightforward expression. It uses standardized parts and avoids ornament or unnecessary detail. It provides for its purpose adequately, completely and without compromise.” He identified three masters of the Style: Walter Gropius and Mies van der Rohe in Germany and Le Corbusier in France. Displayed at the exhibit was an apartment house from Stuttgart, Germany designed by Mies in 1927 which bears many of the characteristics of the Heath Street Houses.

Hitchcock described four guidelines of the International Style and each is illustrated at Heath Street.

Volume over mass. The true character of the building must be evident in the construction. The Heath Street Houses have load bearing walls of concrete block faced with brick but they are not heavy looking buildings. The flat roof was an essential aesthetic point of the Style since it did not hide the character of the building. The entrances at Heath Street are at the corners of the wings of each block which adds to the private, domestic feel of the buildings.

The surface material must be of one even texture. The cheapest brick is often the best because it keeps a permanent color, does not crack and streak, comes in different shapes and can be laid in different patterns. Brick is also the best material for large low cost construction.

Buildings must have a regular rhythm in the use of standardized parts, shapes and a sense of order in the placement of the parts. This was in direct response to the chaos of architectural styles, building sizes and congested street patterns of the 19th century city. Moving housing away from this chaos had been one of the most significant issues with housing reformers for decades. The order of the Heath Street Houses of standardized materials. uniform massing and Beaux Arts formality in the placement of the buildings was in total opposite to the disorganized housing it replaced.

Avoidance of applied decoration and restraint in the use of color. American architecture had been reducing and streamlining the use of facade decoration since the 1920’s but especially with the Art Deco style of commercial buildings in the 1930’s. The International Style destroyed ornament altogether. They advocated sleek buildings in which the windows were the most decorative detail. Windows created a rhythm in their placement in the thin walls of the buildings and the window frame material provided contrast in color with the building facade material, usually a light colored metal against the darker brick.

Architectural ornament was opposed because advocates of the International Style wanted to stress the universal over the particular. They wanted no reminders of historical forms. They rejected the excessive sentimentality about homes of the past such as the Colonial Revival, which was then well on its way to becoming the quintessential American architectural style.

After 1934, the International Style and the Zeilenbau patterns became the standard for the Public Works Administration Housing Division and later the USHA. The architectural style and site plan offered huge cost savings. It helped solve the severe cost restrictions imposed by the Byrd Amendment to the Wagner Act. Ready made design, standardized parts, and cheap, cast materials kept construction costs - and hence rents - down.

World War II stopped low rent housing construction across the country. In Boston, the proposed development for the South End was postponed for a over decade. The Heath Street Houses was managed for twelve years as a single development until its neighbor Bromley Park was completed in 1954 when the two developments were merged into one managerial unit. Bromley Park has its own history based on the policy stated in the second housing act in American history, the Taft- Ellender Housing Act of 1949.

II. BROMLEY PARK

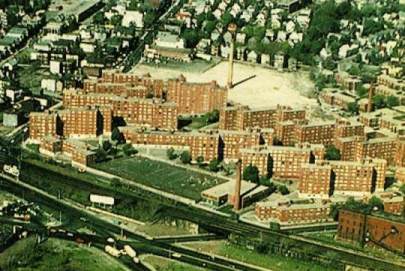

An aerial view of Bromley Heath development taken in April 1977. The Lowell Estate stretched from Centre Street, shown on the far right, to the ridgeline of the housing cornices. The smokestack is all that remains of the huge Plant Shoe factory that burned on February 2, 1976.

The demand for housing and the spread of slums was even greater after 1945 and to remedy both of these urban problems, Congress passed the Omnibus Housing Act of 1949 ( often called the Taft - Ellender Act after its chief Senate sponsors ) which reauthorized, amended and expanded the 1937 Wagner - Steagall Act. It was under the 1949 Housing Act that the Heath Street development was enlarged with the construction of the apartments at Bromley Park.

The 1949 housing bill was no easier to pass than its predecessor in 1937 and mostly for the same reasons: opposition from real estate interests. But the times were vastly different too: the 1937 housing act was born out of the Great Depression when unemployment was high and decent affordable housing was low; indeed, Congress doubled the appropriation for low housing construction in 1939 because the economy had taken a drastic downturn turn. In 1949 America was basking in the warm air of post war prosperity and low income housing was not seen nationwide as being an urgent need; there were no Broadway plays about low cost housing in 1949 as there had been in 1938. The housing problem had not disappeared,though. Statistics from the Federal Bureau of the Census revealed that 30% of American families in 1947 had incomes of less than $2500 which meant they could afford rents of only $27 a month. New homes were out of the question for this group of Americans given that the average house was being sold for $7000.

But the Republican landslide in the Congressional elections of 1946 was interpreted to be a repudiation of the New Deal. More to the point, Americans were just tired of social problems. Still the movement from a wartime to a peacetime economy was painful for everyone and there was a wide group of Americans that prosperity failed to reach:

Families without workers.

Non whites, mostly blacks.

Broken families.

Relief cases.

The aged.

These were the tenants which made up a large part of the second wave of public housing in Boston built between 1950 and 1954. Along with this group of chronically poor people came attendant social problems that housing managers now had to understand and learn to resolve.

After four years of failure to pass a new housing bill, Congress convened early in January, 1949 and took up S1070, a housing act with very broad bipartisan support. Introduced by Senator Allan J. Ellender ( Democrat of Louisiana ) and Senator Robert A. Taft ( Republican of Ohio ) on February 25,1949, the bill had eleven Republican and eleven Democratic sponsors including Henry Cabot Lodge of Massachusetts, Margaret Chase Smith of Maine and Wayne Morse of Oregon.

The Taft -Ellender bill was introduced at the same that the Cold War had settled over American political life to freeze and polarize political debate for the next forty years and both advocate and opponent alike argued the housing act in anti-Communist rhetoric.

When the Senate took up debate on the bill on April 14,1949, Ellender said that the legislation was important because the way the defeat Communism was to make democracy work.” foreign ideologies will not appeal to our people if they can obtain decent shelter in which to live and pleasant surroundings.”

“The American people,” Raymond Foley, the Administrator of the Housing and Home Finance Agency, said in a speech on April 4, 1949, “ have a right to expect the American system to work in such a fashion that it will develop opportunity.”

On the opposite side, Congressman George A. Dondero of Michigan said that if this “ colossal program” is adapted, “ the Russian ideology will have gained a foothold on the shores of freedom.”

Congressman Frederick C. Smith of Ohio stated that the bill was nothing but Communistic and suggested that the title be changed to “ A bill to further enslave the people of the United States.”

Congressman John W. McCormack said it was amusing to hear members denounce the bill as socialism since “ those very people have been in fact the strongest advocates for government aid and assistance.” ( Most of all new private sector housing starts, for example, were made possible by mortgages guaranteed by the federal government, the most popular public housing program then and now in the country ).

On June 6, 1949. McCormack introduced the results of research he had requested which showed that, far from being socialistic, the housing bill was supported by the United States Constitution. He made a strong case that Federal public housing was authorized under Article I, which gave to Congress the power to lay and collect taxes for the general welfare. ( for the full text of McCormack’s research, see the Congressional Record, 81st Congress, 1st Session, Appendix I, page A 3483 ).

The usual quintet of opposition was in full force throughout the winter and spring of 1949:

The US Chamber of Commerce

The National Association of Real Estate Boards ( NAREB )

The US Savings and Loan Association

The national Association of Retail Lumber Dealers

The National Association of Home Builders

These groups had never stopped fighting public housing even after passage of the Wagner - Steagall Act. “ The United States Housing Authority projects now underway are undiluted socialism,” bellowed the NAREB in 1939.

On April 14,1949, One of the sponsors of the housing bill, Senator John Sparkman of Alabama vented his impatience at this relentless opposition,

“We have never really had a fair test of public housing. We started public housing before the war and before we really had a chance to test it , we were in the war. Housing is a national problem.” The Housing Act of 1949 . he said, is a fundamental measure to improve the living conditions of the American people.

The adjective “ public “ before the word housing rattled the private sector and Sparkman tried to alleviate that by saying many people[ get the wrong idea that the federal government owns housing. It was owned by local communities and local housing were authorities established under state laws. The NAREB was unmoved: housing, it said, should remain a matter of private enterprise and private ownership.

As the Heath Street Houses showed, public housing was in many ways a private enterprise: local real estate men got the fees for appraising the properties, it was designed by private sector architects, built by private sector contractors using private sector suppliers, truckers and tradesmen from masons to bricklayers, plasterers to electricians.

As page after page of testimony showed, the private sector could not meet the housing needs of a very large part of the American people,” Private enterprise,” said Senator Ellender, “ even with the aids presently available to it, is unable to meet the total housing needs of the American people because it cannot produce houses at the prices and rents which a large portion of the American people can afford.”

Arrayed against the opposition quintet was another formidable group of five who supported the bill:

The AFL - CIO

The US Conference of Mayors

The American Municipal Association

The NAACP

Veterans organizations

They had their voice in President Harry S. Truman. Housing legislation was in suspension in the four post war years largely because Truman, serving out the term of President Roosevelt who had died in office in April, 1945, did not have good relations with Congress; and after the 1946 Republican sweep of both the Senate and House, that party saw him as a lame duck president who would soon be gone. But Truman’s unbelievable victory in the presidential election of 1948 changed all that: he was now president in his own right and one of the highest priorities of his Fair Deal was the housing bill.

The debate on the bill in the Senate lasted seven days, from April 13 to 21, 1949; the House hearings took a month, from April 9 to May 7th. But during the House - Senate Conference formed to reconcile the two versions of the legislation, debate was so acrimonious and the real estate lobbying so intense, that the Truman administration feared that the bill might fail to pass. On June 17,1949, Truman signed a letter written by the White House counsel and the head of the Housing and Home Finance Agency to Speaker of the House Sam Rayburn which said,

“ I have been shocked in recent days at the extraordinary propaganda campaign unleashed against this bill by the real estate lobby. I do not recall ever having witnessed a more deliberate campaign of misrepresentation and distortion against legislation of such crucial importance to the public welfare… [ it ] consistently distorts the facts of the housing situation in the country … The real estate lobby continues to cry socialism in a last effort to smother the real facts which this bill is designed to meet. [ It is a ] malicious and willful appeal to ignorance and selfishness … The American Legion, Jewish War Veterans, AFL, the US Conference of Mayors … all of them have seen through the charge of socialism and support the bill [ as ] necessary to the public interest.”

The basic difference between the House version and that of the Senate was contained in Section II: Amendments to the National Housing Act. The Senate version provided for 810,000 units of housing with $308 million a year in annual contributions to the local housing authorities over six years. The House wanted 1,05,000 units and $400 million in annual contributions over seven years. In the conference committee the Senate version prevailed and President Truman signed the bill into law on July 15, 1949 ( 63 Stat. 81st Congress, Ch 338 1949 ).

The 1949 Taft - Ellender Housing Act differed in one very substantial way from the 1937 Wagner - Steagall Act: where the 1937 Act was strictly dedicated to low rent housing, the 1949 bill included Title I, Slum Clearance and Urban Renewal as well as the authorization to build 810,000 units of low rent housing nationwide. If job creation helped mightily to win passage of the 1937 public housing law, in many ways urban renewal made possible the 1949 Housing Act. The 1949 bill was acceptable to many House members only because of Title I and most mayors across the country supported the bill because of what slum clearance would bring to increase their city’s tax base. Senator Hubert H. Humphrey of Minnesota recalled his tenure as mayor of Minneapolis in his remarks in support of the bill.

“The Housing Act of 1937 was basically a public housing act. This particular bill is pointedly directed at slum clearance. Municipalities cannot live on public housing. Municipalities which are required to pay for education, health, sanitation, police and fire costs cannot live on the rents coming from public housing. “

Humphrey favored Title I, the Community Redevelopment section of the bill, because it would do the most for big cities. Yet he admitted that although slum clearance was the heart of the bill, if the public housing section was eliminated, Title I alone would be useless. Urban renewal would force the relocation of thousands of families and public housing was needed to house them. Urban renewal could not start until public housing facilities were built. “ S1070 is a balanced bill, “said Humphrey. It had public housing and slum clearance.

The Housing Act of 1949 committed the United States to “ the goal of a decent home and suitable living environment for every American family”. In a major change from the 1937 law, Title III, Low Rent Housing, Section 301 of the bill established not only minimum income limits for admission but maximum limits for continued occupancy. This provision of the housing law would over time come to change the culture of public housing developments from one of mixed income communities to a homogeneous community of the very poor. No income levels were set; these would be determined at the local housing authority level subject to approval by the US Public Housing Administration. Section 302 explained that preferences in the selection of tenants were to be given first to families displaced by any low rent housing project or slum clearance initiated after January 1, 1947 and disabled veterans were to be at the top of that list of applicants. Families of other veterans and active duty servicemen were next. Section 303 increased the cost per unit to $1750. If an acute need for housing could be demonstrated by the local housing authority or if design and livability standards had to be sacrificed, the cost per unit could be increased to a maximum of $2500 with the approval of the US Public Housing Authority. The total authorization for annual contributions was set in the bill at $08 million. In the first year beginning July 1,1949, $85 million was authorized for annual contributions and $25 million in loan funds.

The Housing Act specified that over a six year period, 810,000 units of housing could be built not to exceed 135,000 a year. But like the Wagner - Steagall Act, the 1949 Housing Act was not able to gain any momentum. Almost immediately, the Korean War halted construction in the middle of the first full year of operation. On July 18,1950, President Truman set a limit on public housing starts to just 75,000 in order to conserve steel and other raw materials for the war effort. This interruption gave the real estate lobby an opportunity to get Congress to further reduce the number of units to be built. In January of 1953 at the start of the Eisenhower administration only 156,000 units had been built nationwide after three and one half years. If the opponents of public housing could not stop housing legislation, they could dilute it.

Bromley Park was built under the F/Y 1952 authorization of 50,000 units of housing. The times were vastly different from the days when Heath Street was built. First, of the five man Board of Directors of the BHA only John Carroll remained as the only original member with an invaluable institutional memory. He was also a strong advocate for housing the aged, which became a hallmark of Bromley Park.

In 1940, the Boston Housing Authority was primarily occupied with the design and construction of public housing; it managed only one development at Old Harbor Village and that was under lease agreement with the USHA.

In April of 1950 when the BHA first turned its attention to expanding Heath Street, it was not only the manager of the first eight developments built under the 1937 housing act it was also the construction manager of several large State -funded veterans housing developments in the period between 1946 and 1950 ( such as the Arborway Veterans Housing near the West Roxbury District Court in Jamaica Plain; sold to a private investor in 1955 ). In addition, during the four years from concept to completion of Bromley Park, the BHA built no less than twelve developments across the city, a mixture or federal and state funded projects. These were:

Archdale in Roslindale ( State aided housing )

West Broadway in South Boston ( State aided )

South Street in Jamaica Plain ( State aided veterans housing )

Orient Heights in East Boston

Columbia Point in Dorchester

Cathedral in the South End ( delayed by WW II )

Mission Extension in Roxbury

Washington - Beach in Roslindale

Commonwealth - Faneuil in Brighton

Franklin Field in Dorchester

Franklin Hill in Dorchester

Whittier Street in Roxbury

Fourth and finally the BHA was until 1957 the City of Boston’s development agency charged with implementing Title I, the urban renewal provision of the of the housing act. During the four years of Bromley Park’s construction, the BHA managed the start of New York Streets urban renewal site ( bordered by Dover, Albany and Washington Streets and the NYNH + H R/R right of way), and laid the ground work for Charles River Park and the Prudential Center. So in addition to the complex problems of tenant selection and reviewing income levels as mandated by the 1949 housing act, the BHA had to face the enormous challenge of rehousing those families displaced by the New York Streets Urban Renewal Project.

On April 26, 1950, the BHA Board ordered a feasibility study of the thirteen acre site bounded by Bickford, Heath and Centre Streets and the NYNH + H R/R viaduct to determine its potential as a housing site. This mainly rectangular shaped site was at a slightly higher elevation than Heath Street and included a ridge of Roxbury conglomerate in the middle nearest Centre Street. The land had the advantage of being located on two major roads, Heath and Centre Streets. Although far more open today, the site was blocked on its Bickford Street side by the looming walls of the Plant Shoe Factory ( which burned in 1976 ) and on its southeast side by the twenty foot wall of the railroad viaduct ( razed in 1981 for the Southwest Corridor ).