Colonial Era

Jamaica Plain has its own Revolutionary patriot although Brigadier General William Heath might not be considered a hero. Rather, it could be said that General Heath was a defensive soldier; his career was spent in defense, notably the strategic Hudson River Forts his troops defended when was at command at West Point.

A talk by Hidden Jamaica Plain about their research into the remarkable letter written by Sarah Winslow Deming about how she escaped British-occupied Boston and took temporary refuge in Jamaica Plain in April 1775. Lucinda, whom Sarah enslaved, was with her and this talk focuses in on what is known about Lucinda. Presentation given April 28, 2025.

The Massachusetts Historical Society collection contains a vibrant account of the first days of the American Revolution in Boston by Sarah Winslow Deming (1722-1788). She wrote a 12-page letter to her niece Sally Winslow (later known as Sarah Winslow Coverly) sometime in June 1775, two months after the battles of Lexington and Concord occurred on April 19. Her letter shares an unusual account of the outbreak of the Revolutionary War from the point of view of a 52-year-old woman and conveys a vivid sense of what was happening in Jamaica Plain.

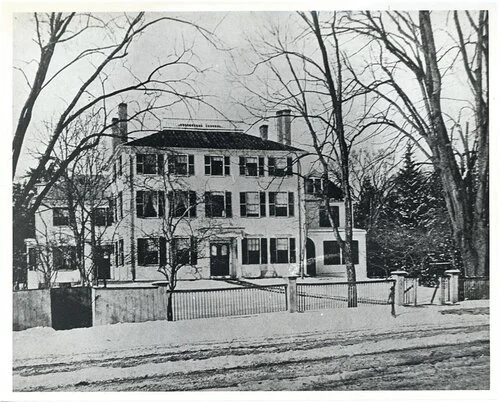

Today we know the Loring Greenough House as a historic property located in the heart of Jamaica Plain’s Monument Square. It was constructed in 1760 by Commodore Joshua Loring and was owned by the Greenough family from 1784 until 1924. The Jamaica Plain Tuesday Club, a local women’s organization, purchased the house in 1924 and has stewarded it since then. The house is also intimately linked to the history of enslaved and indentured people since both the Loyalist Loring and the pro-Revolution Greenough families enslaved and indentured people.

Flora was a Black woman enslaved in what is now Roslindale when slavery was legal in 17th and 18th century Massachusetts. Many European white colonists of all classes enslaved Black and Indigenous people in small numbers to perform a range of household labor, including skilled work, such as carpentry, child care, spinning cloth, milking cows and domestic chores. While the colony did not have large agricultural plantations that required many enslaved people to work the fields, as in the South, there were quite a few small commercial farms that raised crops for market and extracted profit from the labor of enslaved people to enrich their enslavers.

A talk by Hidden Jamaica Plain - in the 18th and early 19th centuries, the families living at the Loring Greenough House and farming their estate in JP used the labor of enslaved and indentured people. Scant information has long been known about their presence; recent research has uncovered more details. This talk outlines these new findings and the ongoing study being conducted by volunteers. Video of a talk given on June 10, 2024

Details of the life a young boy by the name of Dick Morey. On July 30, 1785, his enslaver John Morey sold Dick for five pounds to David Stoddard Greenough. On September 6, 1786, a year after Greenough purchased Dick, he changed the legal basis to a formal indenture. Dick presumably worked for Greenough in Jamaica Plain for the next twelve years. However, the evidence suggests that Dick ran away three years before the end of the indenture.

A talk by Hidden Jamaica Plain about their research so far that covers the indigenous presence in the area, the details of 27 enslaved people that have been uncovered (along with their enslavers) and information about free Blacks who were associated with the First Church. Video of a talk given on January 28, 2024

Eleazer Weld, was known as a Revolutionary War hero but there is a great contradiction in his life story. While serving his fledgling country and helping to found local institutions Eleazer Weld also enslaved and indentured people, both African and White for at least 28 years.

Moussa Deyaha’s journey to Jamaica Plain started in Africa. His encounter with the slave-trading and enslaving Perkins family in St. Domingue (today’s Haiti) brought him to Boston for 39 years. We have no documentation of Moussa Deyaha in his own words. Instead, what we know of him is filtered through the biased narration of the Perkins family who enslaved him. But even viewed through the Perkins lens, Moussa Deyaha’s courage, resilience and survival skills shine through.

Cuba, an African woman, was being held under house detention in Jamaica Plain in fall 1777 when she filed a petition for her freedom. Cuba had been a passenger aboard the British packet ship Weymouth [2,3] bound from Jamaica to London when it was captured by the Connecticut Navy Ship Oliver Cromwell on July 28, 1777 during the American Revolutionary War.

In colonial times, the system of slavery was a primary economic driver in the Northern colonies including New England. Because colonists chose to grow their economy using enslaved labor, it was the standard practice of many New Englanders to enslave other human beings – both Indigenous and African people. New Englanders ran the Triangle Trade, enslaving, buying, and selling people. Jamaica Plain was part of all of this history and at least 27 people were enslaved here.

The fortune of the Perkins family of Pinebank was deeply entrenched in the slave trade and products produced with enslaved labor before they moved over to the China Trade (which itself was dependent on the illicit importation of opium).

City of Boston Archaeologist Joe Bagley speaks about his latest book Boston’s Oldest Houses and Where To Find Them. Video of a talk that was held via Zoom on May 25, 2021.

Prof. Dane Morrison speaks about the China Trade, with a focus on the travels of the Forbes family, from Jamaica Plain to China. Video of a talk that was held via Zoom on March 21, 2021.

En route to a recent meeting this chronicler was on the southern end of Blue Hill Avenue. On the outbound side, a rectangular granite marker almost four feet high, eight inches thick and nearly two feet wide was revealed. It had to be an early milestone in the tradition of the Judge Paul Dudley milestones (seen in finest form at the Civil War Monument here in JP).

An historic old house is the old Hallowell homestead in Jamaica Plain. It is nearly 170 years old, having been built in the year 1738 by Capt Benjamin Hallowell.

A house, like a man, can have a life-story and a destiny. Over on Pond Street there is a venerable structure which has had a stormy, varied history but a seemingly singular destiny – to nourish and sustain education, refinement and art.

Five monuments remain in the early Roxbury town limits (including West Roxbury and Jamaica Plain until 1851), untouched for the most part by politics, urban redevelopment, and other forms of change and still performing their original function (if one knows how to read them). There is another five such monuments that can be found in Brookline, Brighton, and Dorchester. They are milestones showing the distance to the Boston Town House (now the Old State House).

Jamaica Plain is home to the fourth-oldest school in the country. The Eliot School was founded 329 years ago in 1676. On Oct. 2, 1676, 38 “inhabitants of Jamaica or Pond Plain” got together and pledged money, payable in corn, to support the school for 12 years. Now called the Eliot School of Fine and Applied Arts, the institution thrives to this day, offering classes to children and adults days and evenings, taught by highly skilled artists and crafts people.

On Memorial Day members of the Jamaica Plain Historical Society and the First Church decorated the grave of Revolutionary War Soldiers Captain Lemuel May and others for the first time in many years.

An interesting address on “Jamaica Plain in Colonial and Revolutionary Times” was delivered by Frederic Gilbert Bauer yesterday to the Bostonian Society. Mr. Bauer remarked in opening that while the interest of many towns and cities was centered around stirring events which occurred in them, Jamaica Plain had no such incidents connected with her history.

This article is based on a talk by Marcis Kempe, Executive Director of the Metropolitan Waterworks Museum, presented on December 7, 2014 at the Arnold Arboretum in Jamaica Plain. Mr. Kempe, an avid water-supply historian, discusses the early attempts by Boston residents to find drinking water on Shawmut peninsula. A system of wood pipes led eventually to the establishment in 1796 of Boston’s Jamaica Pond Aqueduct Corporation, which piped water directly to homes and businesses.

Too many people in this area of Massachusetts believe Francis Drake's statement in his History of Roxbury (of which Jamaica Plain was a part) that no traces of aboriginal occupation were ever observed there. Proof to the contrary comes from the Indian artifacts from our major tract of mostly untouched land, the Arboretum.

Tucked away on the Walter Street side of the Arboretum just above Weld Street is an almost invisible cemetery, consisting of only eight slate tombstones with burial dates between 1712 and 1812. It also includes puddingstone boulder with a metal plaque erected by the Massachusetts Society of the Sons of the Revolution in 1906.

Several officers and members of the Jamaica Plain Historical Society attended a one-day conference on New England taverns held September 23, 2001 in Weston, Massachusetts. The event, “New England Taverns: A Symposium on Tavern Culture from Colonial Days to the Early Republic,” was held at the Community League Barn of the Josiah Smith Tavern

A footnote in an annotated edition of Petronius's "Satyriancon" not only provides a Halloween story to put in a local setting, but also allows us to focus on a Jamaica Plain landmark in colonial days (unfortunately long since demolished).