The History of 101 Carolina Avenue

#1 - 101 Carolina Avenue, 2020

(see bottom of article for image credits)

At the corner of Carolina Avenue and Lee Street in Jamaica Plain sits a charming cottage on an unusually large parcel of land for the surrounding neighborhood. This house, at 101 Carolina Avenue, was the first to be built on the street. Though significant for its age, also important is the role it played in the history of Jamaica Plain and the development of the field of social work. Between 1853, when the house was constructed, and 1913, most of the owners and occupants of 101 Carolina Avenue were related by marriage, blood, or business ties. In 1913, the house transformed from a single-family home into the home of the Jamaica Plain Neighborhood House Association, a settlement house that served the working people of Jamaica Plain and the influx of immigrants moving into the neighborhood. In this article, we will explore the history of the people who lived within its walls and, later, its life as a settlement house.

#2 - 101 Carolina Avenue, 2020

Architecture

101 Carolina Avenue is a two-story, single-family, wood-framed house with a Roxbury puddingstone foundation. Based on the historical record, the house was likely built by two professional house painters, George G. Drew and David C. Talbot, sometime between 1853 and 1855. Typical of the architectural styles of the mid19th century, the house is an Italianate cottage with Greek Revival and Gothic Revival details. The pattern for the cottage was likely taken from Andrew Jackson Downing’s influential 1850 pattern book, The Architecture of Country Houses, the house nearly mirroring the pattern “A Small Cottage of Brick and Stucco, in Gothic Style.”

Possibly due to the limited finances of Drew and Talbot, the cottage is constructed in wood rather than brick and stucco. The builders also forwent the decorative gothic details that are illustrated in Downing’s pattern. Downing suggested that builders might simplify the architectural style of his design “as to render it sufficiently truthful to express the life and means of the occupant” (Downing, 1850, pg. 101). For example, he recommended substituting the gothic windows in the attic rooms with square-headed windows and simplifying the form of the bay window, advice that Drew and Talbot followed when constructing 101 Carolina Avenue.

#3 - 101 Carolina Avenue, 2020

Greek Revival influences on the 101 Carolina Avenue cottage include the gable roof, the wide cornice along the roofline, and the rectangular transom and sidelights at the front door. The Gothic Revival elements include the bay window at the front of the house and the one-story porch facing Lee Street. Queen Anne architectural details were a later addition to the house, specifically the turned porch spindles, which would have been added after 1890.

Original house plans no longer survive for the cottage, but we can determine a few additions to the property by studying Boston Inspectional Services permits. In 1924, owner Patrick C. Mulvey covered the back porch and constructed the current brick-and-concrete, two-car garage. Two decades later, owner E. M. Brown covered over the house’s clapboard siding with stained wooden shingles.

Let us turn now to the owners and occupants of the house and its life as the home of the Jamaica Plain Neighborhood House Association.

We begin with the owner of the original land, David S. Greenough III.

David S. Greenough III

In 1832, Harvard-educated lawyer and merchant David Stoddard Greenough III inherited from his father "five acres of Jamaica Plain farm land, four acres of orchard, five acres of salt marsh in lower Roxbury, and a Brookline wood lot containing six acres” (Boston Landmarks Commission, 1999, p. 15). His inheritance included a portion of the 80 acres of farmland that the Greenough family had owned in Jamaica Plain since 1784. Upon his mother’s death in 1843, Greenough inherited his family’s home, the Georgian mansion at the historic center of Jamaica Plain that we now know as the historic Loring-Greenough House.

John G. Hales’s 1832 Map of the Town of Roxbury illustrates that the Greenough estate in Jamaica Plain was a vast stretch of uninhabited land. The landscape changed in 1838 when the five Greenough siblings began to split up their family’s land for suburban residential development, contributing to the transformation of Jamaica Plain from a rural village to an urban “streetcar suburb.” In 1850, David S. Greenough III divided his farmland holdings into 60 lots. These lots ran along Carolina Avenue, Lee Street, Keyes Street (later McBride), Starr Street (later Everett), and the Boston and Providence Railroad. A majority of the lots were sold to working-class buyers, including laborers, carpenters, stone layers, and blacksmiths.

On September 1, 1853, Greenough sold for $1,508 an 18,097 square-foot lot located at the corner of Carolina Avenue and Lee Street to two West Roxbury house painters, George G. Drew and David C. Talbot. That lot would become 101 Carolina Avenue.

George G. Drew

George G. Drew was born in Wakefield, New Hampshire on February 15, 1816. In 1840, Drew married 16-year-old Rhoda R. Davis of Maine in a ceremony in Boston, Massachusetts. Together they had four children: George G., Charles S., Christopher W., and Alata (“Lettie”). In 1866, George’s wife died of cancer at the age of 45. The following year, he married 30-year-old Medora C. Riley of Boston.

#4 - The Jamaica Plain Neighborhood House at 101 Carolina Avenue.

Drew worked as a house painter from the age of 22. Between 1850 to 1853, he ran a paint shop, “Talbot & Drew,” with his partner David C. Talbot at the corner of Centre and Burroughs Streets in Jamaica Plain. By 1868, Drew owned his own storefront at the corner of Centre and Thomas Streets.

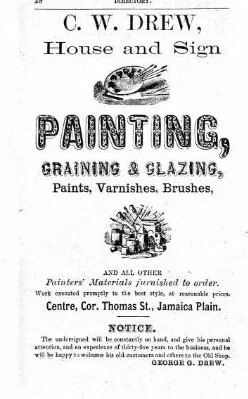

Later, George Drew’s son Christopher W. took ownership of the business. An 1873 Boston City Directory advertised Christopher’s house and sign shop, “C.W. Drew.” According to the ad, the store provided painting, graining and glazing services and sold paints, varnishes, brushes, and “all other painters materials furnished to order.” The ad also indicated that his father worked at the old shop full-time. Later, Christopher moved his storefront to Starr Lane, near Centre Street, and renamed it “C.W. & Son,” suggesting that his own son also joined the family business.

In addition to co-owning a painting business, George Drew and David Talbot purchased two properties together. The first was a parcel of land on Mount Vernon Street in West Roxbury that they bought in July of 1852. The following year, on September 1, 1853, the two men acquired Greenough’s lot at 101 Carolina Avenue. According to the 1855 Massachusetts Census, George Drew and his family resided at that address, indicating that Drew and Talbot built the cottage at 101 Carolina Avenue sometime between 1853 and 1855.

On June 11, 1854, Drew expanded his property by purchasing from Greenough the lot next door at 105 Carolina Avenue for $1,096.

In 1855, Drew and Talbot fell into debt. Because of their subsequent insolvency, the two men were forced to sell Drew’s home at 101 Carolina Avenue and his adjacent lot at a public auction on October 9th of that year. David S. Greenough III, the former owner of the two lots of land, ended up being the highest bidder. Greenough re-acquired his family’s land and the newly constructed house at the bargain price of $293, a $2,311 loss to Drew and Talbot on their initial investment.

#5 - Downing’s Pattern for “A Small Cottage of Brick and Stucco, in Gothic Style”.

David C. Talbot

David C. Talbot was born in Massachusetts in 1819. On March 20, 1845, he married 22-year-old Mary B. Gregory. Together they had four children: George H., Charles G., Fredrick L, and Mary.

Talbot worked as a house painter for at least 25 years, including running the painting business with his partner George Drew. By 1869, Talbot was also practicing as a glazier. His two sons, George H. and Fredrick L., eventually followed in their father’s footsteps and became painters. His third son, Charles G., worked as a bookkeeper, possibly balancing the books for the family painting business.

Talbot and his immediate family lived in West Roxbury between 1850 and 1868, including a house on Green Street in Jamaica Plain. The family shared their homes with other professional painters, including David Talbot’s cousins, the Woodwards. One of those cousins was his first cousin John C. Woodward, a painter and veteran of the Battle of Gettysburg. As we will learn later in this history, John C. Woodward would eventually move into the house his cousin David C. Talbot built at 101 Carolina Avenue, decades after the house was constructed.

On June 23, 1871, David Talbot’s wife Mary died at the age of 47. By 1874, Talbot moved to Norwood, retired from the painting profession, and took up farming. The 1880 Federal Census indicated that he owned and managed 26 acres of agricultural land with no hired labor. According to a Boston Globe article from 1884, Talbot also worked as a milk producer and was a member of the New England Milk Producers’ Association.

In 1897, David C. Talbot died in Norwood at the age of 78. Six years prior, his former partner David G. Drew died from apoplexy and heart disease at the age of 75.

Despite losing their Carolina Avenue properties in 1855, Drew and Talbot left behind a legacy on Carolina Avenue and in the larger neighborhood of Jamaica Plain. Their house was likely the first house built on Carolina Avenue and is now the oldest surviving house on the street. An 1858 map of Jamaica Plain illustrates that only four buildings existed on Carolina Avenue at the time, nine years after the street had been laid out. The owners of those buildings were J. Gardner Weld, William H. Goodwin, Joseph H. Rowe, and David S. Greenough III. Rowe and Goodwin purchased their lots in 1854 and 1855, respectively. Weld purchased his property on the corner of South Street and Carolina Avenue in January of 1853, the same year Drew and Talbot purchased 101 Carolina Avenue. However, the Welds were not yet residing at that address by 1855, suggesting that Drew and Talbot’s house was the first on the street. Though more modest in size than Weld’s future estate, which reached from Carolina Avenue to Child Street, Drew and Talbot’s property would end up playing an outsized role in the neighborhood.

David S. Greenough III (again)

It is likely that David. S. Greenough III rented out 101 Carolina Avenue after he purchased the property back from Drew and Talbot in 1855; Greenough was living at the Loring-Greenough House at the time, and would reside there until his death in 1877. However, it is not clear who were the Carolina Avenue tenants while the house was under Greenough’s ownership.

#6 - Advertisement for C.W. Drew, house and sign painting store

Almost seven years later, on December 6, 1862, Greenough sold 101 Carolina Avenue to Orrin J. Young, a yeoman (a farmer who cultivates his own land) from West Roxbury.

Orrin J. Young

Orrin J. Young was born in Barnstead, New Hampshire in 1831. Throughout his life, Young worked as a coachman, yeoman and milk dealer. On September 13, 1859, Young married 21-year-old Andora (“Dora”) Emma Crane, a native of Ireland. Both Orrin and Dora were living in Dorchester at the time of their marriage. The following year, the couple moved into the West Roxbury home of Englishwoman Mary B. Curtis along with their one-year-old son Thomas H.

In December of 1862, the Youngs purchased 101 Carolina Avenue. It’s possible that either Drew and Talbot or Greenough added a barn at the rear of the property before the Youngs moved in; a map from 1874 shows a barn behind the house and the Youngs’ deed indicates that there were multiple extant buildings on his new property.

Dora gave birth to two more children -- Harry Joseph and Lillian May -- while the family lived on Carolina Avenue. On May 3, 1870, the Youngs sold 101 Carolina Avenue to Hosea B. Stiles for $2,700. The Youngs then moved to Walpole where they would welcome another son and daughter into their family -- Fredrick Charles and Minnie Gertrude – and where Orrin continued to work as a farmer.

Orrin Young lived in Walpole until 1888, when he died at the age of 57.

Hosea B. Stiles

The next owner of the house, Hosea Ballou Stiles, was born in Grafton, Vermont on January 29, 1805. On August 15, 1841, Stiles married 32-year-old Sarah Mirick of Massachusetts. Together they had two children, Anna (“Annie”) and George M.

Throughout his adult life, Hosea worked as a yeoman, laborer, teamster, expressman, and for a brief period of time, as an employee at a picture store. He and his wife also invested in real estate, buying and selling property in Jamaica Plain along Willow Street (later Green Street) and Boston Avenue (later Lamartine Street).

The Stileses began their married life in Roxbury. In June of 1846, they paused their Roxbury residency for six months to move to Hopkinton. This temporary move was likely due to financial difficulties. By the time the family moved back to Jamaica Plain that November, Hosea was considered an insolvent debtor and was no longer in business with his co-partner in trade, James E. Barrell, in their Roxbury firm of “Stiles & Barrell.” Additionally, Stiles’s real and personal property was legally transferred to an assignee.

By 1850, the Stileses were living on Centre Street in Jamaica Plain. In 1858, they moved their family to 54 Zeigler Street in Roxbury. Sarah died the following year at the age of 50. Three years later, on May 10, 1862, Hosea married his housekeeper, 36-year-old Martha E. Woodward.

In 1870, Hosea and Martha set their sights on Carolina Avenue. On May 3rd of that year, they purchased 101 Carolina Avenue from Orrin J. Young, and moved into the house with Hosea’s two adult children from his first marriage. Martha may have been interested in the house because her first cousin, David E. Talbot, had constructed it seventeen years prior.

#7 - Inset of the 1891 Bird’s Eye View map showing 101 Carolina Avenue

A month later, the Stileses purchased two lots of land directly behind their house, on what is now 20 Lee Street. This purchase enlarged their property to half an acre. When they first bought the house, Orrin was working at a picture store. By the following year, the Boston Directory identified him as a farmer. It is possible that the Stileses purchased the two additional lots so that Orrin could operate a family farm on the land at the rear of his house. The land was indeed suitable for agricultural use, as we will learn later in this history.

On May 5, 1874, Hosea B. Stiles died from cancer of the stomach at the age of 69. Upon his death, he left an estate worth $12,000 to his wife Martha E. Stiles (nee Woodward), including the house at 101 Carolina Avenue.

Martha E. Woodward (Stiles) Rowe and Joseph H. Rowe

Martha E. Woodward was born in Brookline, Massachusetts on December 19, 1825. On May 17, 1877, three years after the death of her husband, Hosea B. Stiles, Martha married her next-door neighbor, Joseph H. Rowe. Upon marrying Rowe, Martha moved into his house at 65 Carolina Avenue, along with his three children from a previous marriage. She continued to hold onto her property at 101 Carolina Avenue, and by 1880, her three sisters – Mary J. Woodward, Phebe Craig, and Julia A. Guild – moved into the house.

Martha Woodward was a homemaker and a member of the Citizens’ Law and Order League of Massachusetts, a group that fought for better enforcement of the laws regulating the liquor industry. The organization’s work included such activities as preventing children from frequenting saloons as customers and aiding police in prohibiting the sale of liquor on Sundays.

Martha’s husband, Joseph H. Rowe, was a prominent resident of Jamaica Plain who worked as a contractor, real estate dealer and farmer. Rowe’s farm and real estate holdings were significant features of the Carolina Avenue neighborhood; his farm, where he and Martha resided, included 85,600 square feet of land bordered by Carolina Avenue, Lee Street, and Child Street (before being bisected by Verona Street in 1906) – a portion of which currently serves as the Murphy Field and Playground. It is not clear what sort of farm Rowe operated; however, an 1880 U.S. Census indicates that Joseph Rowe was a “dealer in wood.” It’s possible that Rowe cultivated trees for lumber on his Carolina Avenue farm.

Between 1874 and 1890, Rowe built two groups of frame row houses abutting his farm, at the corner of Child and Lee Streets (76-82 Child Street and 17-27 Lee Street), buildings that still remain at those sites. A Boston Landmarks Commission survey indicates that these properties were built to house Rowe’s farm hands.

On January 3, 1903, Joseph H. Rowe died at the age of 75 from arteriosclerosis and “senile pneumonia.” That same year, Martha was diagnosed with breast cancer. These two events may have led Martha to sign her last will and testament in October that year. In her will she bequeathed to her brother, John C. Woodward, her property at 101 Carolina Avenue, with the stipulation that the property be transferred to John’s son, George E. Woodward, upon John’s death.

John C. Woodward and George E. Woodward

John Chivers Woodward was born in Newton, Massachusetts on September 3, 1833. John started working at a young age, serving as a laborer at 15. By the time he was 22, he was employed as a professional house painter, a vocation he would hold the remainder of his life.

On August 10, 1862, John joined the Union Army where he served with the Massachusetts 9th Light Artillery Battery. The next year, his battery fought in its first battle, in the Battle of Gettysburg. John survived the war, and in 1868 married 25-year-old Mary Ann Blizard, a native of New Brunswick, Canada. The couple had one child, George E. Woodward.

George E. Woodward born on June 1, 1871 in Jamaica Plain. Throughout his life, George worked as a teamster, motorman, machinist, signal inspector for the railroad, and a construction foreman and wireman for the Boston Elevated Railway. He also served in World War I as a construction electrician for the Massachusetts Naval Battalion.

Before the age of 57, John Woodward lived with his family in Jamaica Plain, Brookline, and Indianapolis. By 1890, John was divorced and had moved into the house his sister Martha owned at 101 Carolina Avenue, joining at least one of his other sisters, Mary J. Woodward. An 1891 bird’s-eye map of Jamaica Plain shows that a new east-facing wing was added to the house that John’s first cousin, David C. Talbot, built. It is possible that John added that wing, along with the Queen Anne turned porch spindles, after he moved into the house.

On March 11, 1896, George E. Woodward married 23-year-old Alvid (“Alva”) H. Farnham, a native of Nova Scotia. Together they had three children, Ernest John, Grace F., Bessie B. Their son Ernest would eventually serve in the National Guard in the 26th Yankee Division during WWI and see 20 months of active service. Ernest was one of 68 soldiers who volunteered to receive the trench fever test, a test conducted by the American Red Cross in 1917, which studied transmission of the lice-born disease by using human volunteers.

In January 1902, while living across the street from his father at 58 Carolina Avenue, George E. Woodward filed for bankruptcy. Owning no assets, George, his wife, and three children moved in with his father at 101 Carolina Avenue.

After her husband’s death, Martha Rowe moved back into her house at 101 Carolina Avenue, joining her brother John Woodward, her nephew George, and her nephew’s family. In May of 1904, Martha Rowe transferred the ownership of 101 Carolina Avenue to George. The following year, on August 24, 1905, Martha died at the age of 79 after a two-year battle with breast cancer.

Eight years after taking ownership of the house, George breached the conditions of a mortgage that he had signed with Germania Cooperative Bank, and the house went into foreclosure. At 2:00 p.m. on Friday, December 20, 1912, the bank sold the property at a public auction. The highest bidder was the bank itself, at $3,410. John and George Woodward and George’s family then moved out of 101 Carolina Avenue and into a home at 287 Chestnut Avenue in Jamaica Plain.

The following year, John Woodward and two other Jamaica Plain veterans of the Battle of Gettysburg traveled to Pennsylvania for the 50th reunion of the battle, the largest ever Civil War veteran reunion. It was a nation-wide event four years in the planning. Between July 1st and 4th, over 50,000 veterans -- both former Union and Confederate soldiers -- gathered on the former battlefield on camp chairs and under tents to hear speeches, listen to music, watch fireworks, and “rest, smoke and talk over the old days” (Boston Globe, 1913, p. 45).

Four months later, on November 15, 1913, John C. Woodward died at the age of 80 of heart disease while living at the Chelsea Soldiers’ Home. On October 28, 1956, his son George died in Jamaica Plain at the age of 85.

#8 - Advertisement of the activities at the Jamaica Plain Neighborhood House

The Jamaica Plain Neighborhood House Association

As we will explore later in more detail, the Germania Cooperative Bank would eventually sell 101 Carolina Avenue to a settlement house called the Jamaica Plain Neighborhood House Association. The origins of Jamaica Plain Neighborhood House Association arose in the late 1880s during the advent of the settlement movement. The movement employed settlement houses in poor, densely-populated, largely immigrant urban neighborhoods and relied heavily on the work of volunteers. It earned its name from the practice of middle-class volunteers “settling” within the communities that they sought to assist in order to live in, and experience poverty. Instead of providing direct relief, settlements provided educational, cultural and social activities in order to facilitate personal growth and improve the living conditions within the neighborhoods they served. Out of the settlement movement developed the profession of social work, which “eventually replac[ed] the settlement as the principal form of direct social service” (Scheuer, 1985).

Between 1889 and 1895, a group of Jamaica Plain women who were influenced by the settlement movement started three clubs for the working families of the neighborhood: the Jamaica Plain Working Girls’ Club, the Junior Girls’ Club, and the Agassiz Boys’ Club.

#9 - The Neighborhood House Kindergarten Class at 101 Carolina Avenue, March 1917

In 1897, the three clubs came together under the roof of a former schoolhouse on Lamartine Street, located behind the Bowditch School. Their new clubhouse was named the Helen Weld House, in honor of one of the founders of the Agassiz Boys’ Club who had died that year. Opening a central clubhouse relieved the clubs from the cost of rent and fuel, but allowed them to continue with their own directors and control over their own classes. It also established what is one of Jamaica Plain’s oldest social service agencies.

In 1900, being unable to renew their lease on Lamartine Street, the Helen Weld House moved its operations into a house owned by the William H. Goodwin estate at 23 Carolina Avenue. The house was located where the playground for the Margarita Muniz Academy now stands. A Boston Globe article from 1901 summarized the nature of the work at Helen Weld House at the time:

“[The Helen Weld House] provide[s] industrial training and wholesome recreation for the working classes of the community, through the medium of boys’ and girls’ clubs,” efforts that “advance the moral and mental welfare of a large portion of the community” (Boston Globe, 1901, p. 38).

Finding that their settlement work had broadened, the Helen Weld House decided to incorporate as a Massachusetts charitable corporation in 1902. Five years later, the name of the organization was officially changed to the Jamaica Plain Neighborhood House Association.

#10 - Children of the Neighborhood House gardening at 101 Carolina Avenue, 1917

In addition to offering clubs and classes, in 1902, the Association established a neighborhood playground on the grounds of the House at 23 Carolina Avenue. The playground would become a significant feature of their settlement work for decades to come. As explained in the Association’s Annual Report from 1907:

“The importance of the playground cannot be too strongly emphasized…A refreshment, -- when, but for it, many of the little ones would be forced to play in the dusty streets. It is also a strong moral influence in the neighborhood” (Balch, 1953-1954, p. 14).

For years, the directors of the Association endeavored to have the City of Boston take ownership of the playground. Their efforts finally paid off in 1912 when the City purchased 23 Carolina Avenue from the trustees of the Goodwin estate in order to establish a city-run playground. The Association, however, continued to supervise activities at the Carolina Avenue playground.

The sale of the property necessitated the then-named Jamaica Plain Neighborhood House Association to find a new home for their settlement work. The directors decided it was time to buy a building for the Association and put in the time and energy needed to raise the necessary funds.

On February 7, 1913, the Jamaica Plain Neighborhood House Association purchased 101 Carolina Avenue from the Germania Cooperative Bank. The Boston Globe indicated that it was a nine-room frame house on 12,000 square feet of land, valued at $5,000. The Neighborhood House’s new home was just a block away from its former home and the playground that continued to play a big role in the life of the settlement.

The Association moved into the house in March of 1913. Though interior photographs of the house are few, the 1917-1918 Annual Report gave a glimpse into its contents. That year the Neighborhood House had been gifted a piano for the library hall, stationery, wallpaper for three rooms, a pool table, a Victrola and records, pictures, plants, apples, and a gas stove.

The 1913-1914 Annual Report provides an excellent description of the settlement’s members and the setting of 101 Carolina Avenue:

“Our settlement is dealing with a curious amalgam of factory workers, unskilled laborers, rural personal service workers and trade workers, small business dealers and a scattered few who follow a profession. The housing of these various types is also a mixed affair – family-owned homes, separate rented houses, high and low grade tenements, old mansions, altered to house tenements at low rentals and back-or-over the stores of homes of the small shopkeepers…There are the fields and gardens, the parks and woods, chance for tramping and camping, berrying and wild-flower gathering, country games and village gossip, shot through with the sophisticated city pleasures, moving pictures, theatres, dance halls and the less desirable saloon, pool-parlors and haunts of greater evil. In the centre of all these conflicting influences is set our settlement” (JPNHA, 1913-1914, pp. 3-4).

War broke out in Europe a year after the Neighborhood House moved into its new home. To address wartime needs, the Neighborhood House adjusted its work. The 1913-1914 Annual Report stated:

“This crisis has driven us to seek a definite function which the settlement may fulfil in considering the work of peace. Therefore we are discussing a house newspaper, which shall carry the attitude of brotherhood and open-mindedness and an adaption of club programs to stimulate the growth of these large qualities of character” (JPNHA, 1913-1914, p. 16).

The new programming held during World War I included instruction for children and adults in wartime home defense, first aid, home nursing, and classes in citizenship. The House also served as a War Savings Stamp station both to help pay for the cost of the war and teach the importance of saving and thrift.

The Neighborhood House held a variety of classes and recreational activities for its members and the wider neighborhood. There were classes for children in cooking, sewing, knitting, dancing, cane seating and millinery. For the adults, there was a Mothers’ Club, lectures, and English classes for new immigrants. An annual Halloween party served both as entertainment for the neighborhood and a source of fundraising for the House. During the school year the Neighborhood House provided kindergarten classes for children who were not in the public school system. And during the summers there was camping at a farm in East Walpole and garden work for the children.

#11 - Neighborhood House men and their families at the Louders Lane gardens

The children’s gardens were located at the rear yard of the house at 101 Carolina Avenue. In the summer of 1913, twenty children ages 10-14 were enrolled in the gardening program where they cultivated both flowers and vegetables. The following fall, they exhibited their produce at the Annual Exhibition of the Children’s Garden at Horticultural Hall, Boston, and in 1920 were awarded second prize at the Exhibition.

In 1916, the Neighborhood House expanded its gardening program to eleven Jamaica Plain men who were heads of large families. The trustees of a large estate on Louders Lane allotted each man a 3,600 square foot lot in order to grow fresh produce. The program was part of the Jamaica Plain Neighborhood House Association’s campaign to reduce the cost of living while also providing outdoor recreation for the men. The Louders Lane gardens operated until at least 1920.

During the summer, there were also many playground activities for the children. A Boston Globe article from 1915 highlighted the Neighborhood House’s work at the playground:

“Three hundred and fifteen children are making daily use of the Carolina-av Playground, Jamaica Plain. There is a varied program of games and recreative sports…such as ring and singing games in the morning and sewing and dancing in the afternoon. There is a period of story-telling once a week. This week there is an exhibition of sewing and paper cutting” (Boston Globe, 1915, p. 8).

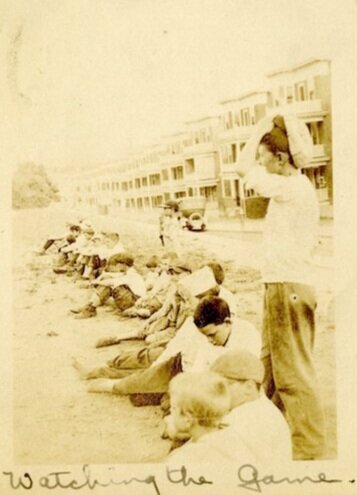

#12 - Boys watching a Neighborhood House baseball game at the Carolina Avenue Playground, 1918

Baseball was central to recreation at the playground. The Neighborhood House organized baseball leagues for 11- to 15-year-old boys and young men. Tam Deering, head worker and director of the baseball leagues, told the Globe in 1918:

‘“It’s a mistake…to lock up all the schools in Summer and dump on the city streets thousands and thousands of boys and girls too young to be employed.” He argued that “during the war we should be more vigilant than ever to see that the boys of today are fitted for citizenship; to take the places of the boys who are going overseas and to meet responsibilities, which, after the war, will be greater than ever before’” (Boston Globe, 1918, p. 7).

Tam Deering’s wife, and co-head worker, also took up the cause of outdoor sports. In 1917, she founded “squash” baseball leagues for girls between the ages of twelve and sixteen. She felt the leagues would keep adolescent girls busy and out of trouble. The sport proved to be so successful that in 1917 or 1918 representatives of the War Camp Community Service came to Jamaica Plain to study the methods used.

In 1917, the Neighborhood House built a second playground in Jamaica Plain. Finding the Carolina Avenue playground inadequate, the directors of the Neighborhood House identified an urgent need for more play space both on Carolina Avenue and in the district bounded by Green, Amory, Boylston and Washington Streets. In response to this need, the boys of the Neighborhood House raised the funds to improve a vacant lot on the corner of Brookside Avenue and Cornwall Street where the children had already been playing during the summers. The Neighborhood House would oversee the playground until at least 1922.

Beginning in 1918, for one evening a week the Cornwall Street playground transformed into a theatre where the Neighborhood House would host outdoor moving-picture shows combined with community singing for around 1,000 people. Today, that site continues to function as a playground and is now known as the William F. Flaherty Playground Park.

#13 - The final baseball game of the Neighborhood House “Midget League” just before presentation of medals and cup

The effort to establish more outdoor recreational space for children reached the front door of the mayor’s house on November 16, 1917. That day, the Neighborhood House organized a group of more than 800 boys to march from the Carolina Avenue playground to the home of Boston mayor James Michael Curley where they held a demonstration in support of expanding the grounds of the Carolina Avenue playground. A 15-piece fife-and-drum corps led the march while some boys held torches and banners. The banners carried messages such as “If you’ll give us a place to play near home, we’ll leave your good green apples alone” and “Strong armies require strong men. Strong men are made on the playgrounds” (Boston Globe, 1917, p. 4).

The unhappy mayor, who was not home at the time, published a strongly-worded letter in the Boston Globe two days later, criticizing the group for “insulting and terrorizing” his wife and children, and accusing the playground’s proponents of foisting upon the city of Boston “at an exorbitant price, properties of questionable value in order that a certain few property owners might benefit and that an unrestricted view of the playground might be possible from the Jamaica Plain Neighborhood House…” (Boston Globe, 1917, p. 24). Tam Deering contested these allegations, arguing that the Neighborhood House had no financial interest in the properties or land in question, land that would allow for expansion of the playground to Lee Street, and that the boys had behaved in an orderly fashion. Despite this rocky start with the City, by 1919, the mayor ordered a $66,000 bond to be issued for expansion of the Carolina Avenue Playground.

In the winter of 1918, the Neighborhood House rented Boylston Hall at 276 Amory Street, the former home of the Boylston Abt Club, a German music club. The Hall made it possible for the House to provide social services in a neglected district while securing space for the Neighborhood House’s larger events.

The 1919-1920 Annual Report described the Amory Street neighborhood as: “…[a] neglected section between the railroad track and the Elevated. It is a mixed population, with pleasant homes backed up to miserable unsanitary tenements. It is also a neighborhood of mixed nationalities, which includes a blend of English, Scotch, Welsh, Irish, Yankee, German, African, Swedish, Jewish and Slavic” (JPNH, 1919-1920).

A headworker from the Neighborhood House explained the dire need of services in the Amory Street district: “I feel sure that if the people of Jamaica Plain knew first hand the Amory Street section where our Neighborhood House is located; knew the swarms of children who live in unfit and over crowded homes, the working mothers who are our best friends and helpers, to say nothing of the liveliest toughest boy proposition I have ever known, money would flow into our treasury” (Jamaica Plain Historical Task Force).

Because of the ongoing needs of the Amory Street district, the Jamaica Plain Neighborhood House Association purchased Boylston Hall in the summer of 1919, after the owner of the building was unwilling to rent it out another year. Even after this purchase, the Neighborhood House continued to hold many of its activities out of 101 Carolina Avenue, including the children’s gardens. In 1920, the Carolina Avenue house also served as a residence for head worker Miss Elizabeth Paine and her assistant Miss Sanders.

The challenge of maintaining the Carolina Avenue and Amory Street properties was a regular source of stress for the directors: “As small stable, adjoining Boylston Hall, which at first brought in $8.00 a month as rent proved to be in poor condition; the roof at Carolina Avenue leaked; Boylston Hall needed painting, alterations, furnishings, repairs, insurance; and the heating plant proved to be unsatisfactory” (Balch, 1953-1954, pp. 11-12).

The expense of keeping both buildings proved unsustainable, and the distance between the two properties was too far for Miss Paine to traverse daily. So, by 1921, all activities of the Neighborhood House were transferred to Boylston Hall and the Neighborhood House Association temporarily rented out 101 Carolina Avenue to a family of four, the Hobarts. The mother, Catherine, was a housewife, and the father, James, a carpenter. Their daughters Christine and Estella worked as a stenographer and telephone operator, respectively.

On July 7, 1922, the Jamaica Plain Neighborhood House Association sold 101 Carolina Avenue to Jeremiah Kelleher of Brookline, who then sold the property to Patrick C. Mulvey four months later. The Neighborhood House continued to operate out of Boylston Hall until 1997 when the settlement house finally closed its doors after 108 years of devoted service to the community.

By Jenny Nathans

December 2020

All the photographs from the Jamaica Plain Neighborhood House are located in this gallery.

Sources

Balch, Marian C. History of the Jamaica Plain Neighborhood House Association. Written in the Winter of 1953-1954. Jamaica Plain Neighborhood House records, box 3, folder 27. University Archives and Special Collections Department, Joseph P. Healey Library, University of Massachusetts Boston.

Boston Globe (1901, October 13). “Table Gossip.”

Boston Globe (1913, June 15). “Carr’s Brigade: Arrangements Complete for its Encampment at Gettysburg.”

Boston Globe (1915, July 26). West Roxbury District.

Boston Globe (1917, November 17). “Pupils Parade for Larger Playground, Jamaica Plain Students in Big Demonstration, Petition Bearing 1000 Names Left at Mayor’s Home.”

Boston Globe (1917, November 18). “Mayor Claims Boys Insulted His Wife, Calls Parade Part of Plan to Raid City Treasury. Neighborhood House Leader Says Marchers were Orderly.”

Boston Globe (1918, September 13). “This Team Averages Less than 10 Years in Age, But Won Title.”

Boston Landmarks Commission Environment Department. (1999). The Loring-Greenough House: Boston Landmarks Commission Study Report. Retrieved from: https://www.cityofboston.gov/images_documents/The%20Loring-Greenough%20House_tcm3-44535.pdf

Downing, A. J. (1850). Architecture of Country Houses, Including Designs for Cottages, Farm-Houses, and Villas, with Remarks on Interiors, Furniture, and the Best Modes of Warming and Ventilating. New York: D. Appleton & Co.

The Jamaica Plain Historical Task Force Place Over Time Exhibit, Jubilee 350. A Brief History of Jamaica Plain. Retrieved from: https://www.jphs.org/jp-history/a-brief-history-of-jamaica-plain.html.

Jamaica Plain Neighborhood House: Annual Report 1913-1914. Jamaica Plain Neighborhood House records, box 1, folder 4. University Archives and Special Collections Department, Joseph P. Healey Library, University of Massachusetts Boston.

Jamaica Plain Neighborhood House Association: Report for 1919-1920. Jamaica Plain Neighborhood House records, box 1, folder 4. University Archives and Special Collections Department, Joseph P. Healey Library, University of Massachusetts Boston.

Scheuer, J. Legacy of light: University Settlement’s first century. New York, NY: University Settlement Society of New York (1985). Retrieved from http://socialwelfare.library.vcu.edu/settlement-houses/origins-of-the-settlement-house-movement/

Ancestry.com

Boston City Directories

Boston Inspectional Services

Boston Public Library. Boston List of Residents. Retrieved from: https://guides.bpl.org/c.php?g=496866&p=3400777

MACRIS

Maps

Massachusetts State and U.S. Census data

Newspapers.com

Norfolk County Registry of Deeds

Suffolk County Registry of Deeds

Maps

1832: https://collections.leventhalmap.org/search/commonwealth:9s161f25j

1858: https://archive.org/details/1858_Map_of_Jamaica_Plain

1874: https://ia800204.us.archive.org/16/items/1874_Hopkins_Map_of_Jamaica_Plain/plate.C.1874.jpg

1884: https://ia802705.us.archive.org/0/items/G.W._Bromley_1884_Map_West_Roxbury_Jamaica_Plain/C.jpg

1891: https://collections.leventhalmap.org/search/commonwealth:x633fc34d

1896: https://ia802608.us.archive.org/0/items/1896_Bromley_Map_of_Jamaica_Plain/plate7.1896.jpg

1905: https://ia902608.us.archive.org/11/items/1905_Bromley_Map_of_Jamaica_Plain/plate.7.1905.jpg

1914: https://ia802707.us.archive.org/34/items/1914_Bromley_Map_of_Jamaica_Plain/plate.7.1914.jpg

Figures

(1 to 3) Photograph by Jenny Nathans

(4) Courtesy of the University Archives & Special Collections Department, Joseph P. Healey Library, University of Massachusetts Boston: Jamaica Plain Neighborhood House records.

(5) Downing, A. J. (1850). Architecture of Country Houses, Including Designs for Cottages, Farm-Houses, and Villas, with Remarks on Interiors, Furniture, and the Best Modes of Warming and Ventilating. New York: D. Appleton & Co.

(6) Boston City Directory from 1873

(7) Norman B. Leventhal Map Center Collection, Boston Public Library

(8 to 13) Courtesy of the University Archives & Special Collections Department, Joseph P. Healey Library, University of Massachusetts Boston: Jamaica Plain Neighborhood House records.