History of 30 Carolina Avenue and 52 South Street

At the corner of South Street and Carolina Avenue in Jamaica Plain is a colorful court that hosts lively tennis, pickleball and basketball games throughout the week. Next door, at 30 Carolina Avenue, is a unique brick building and wooden stable that has housed the Penshorn Roofing Company since 1960 (figure 1). If we stand on that corner and turn back the clock over 170 years, we would visit a time of great transformation and growth for the city of Boston and a family that played a significant role in those changes. We would also learn the story of an entrepreneurial immigrant family and the tragedy they endured.

Figure1: Spiegel sausage factory at 30 Carolina Ave., facing South Street and the tennis court

Architecture of 30 Carolina Ave

30 Carolina Avenue is a one-and-a-half story Second Empire-style building. It was built in 1903 as a sausage factory by August and Augusta Spiegel, a married couple that were proprietors of German delicatessens in Boston.

The former factory rests on a fieldstone foundation and its facades are constructed of brick and wood trim. The prominent mansard roof is characteristic of the Second Empire style. The roof is clad in asphalt shingles (likely slate shingles originally) and has molded cornices and deeply projecting eaves.

The roof includes dormers with eight-over-eight double-hung sash windows. The front roof dormer has a closed gable roof, and the side dormers have hip roofs.

Figure 2: Front door at 30 Carolina Ave.

The front door facing Carolina Avenue (figure 2) is flanked by large windows set in Classical Revival-style wood enframements painted a sky blue. Details include paneled pilasters on either side of the door and windows, with molded panels below the windows. The front door is topped with a transom window with four lights, or windowpanes. The entire front side of the building rests on a brownstone water table.

Let’s now meet the two industrious families that lived in the home that once stood in place of the tennis court at 52 South Street, as well as the story behind the former factory that still stands at 30 Carolina Avenue.

The Evans Family

William Jonathan Richard Evans, Sr. (“William Evans”), was born in Peterboro, New York on September 3, 1811. His wife, Hepzibah Weld, was born on May 31, 1812, in West Roxbury to Joseph Mayo Weld and Lucy S. (Richards) Weld. William and Hepzibah married on September 30, 1834, in Roxbury. Together they had six children, all of whom were born in Massachusetts – Lucy Penelope; William Jonathan Richard, Jr. (“William J.R. Evans”); William Francisco; Eugene H.; Emma W.; and Thomas Weld. Only four children lived into adulthood, and only two past their 20’s.

The Evans family lived in Jamaica Plain, were Unitarians, and members of the First Congregational Society of Jamaica Plain.

William Evans began his career working for the Boston & Providence Railroad Company, in various positions requiring mechanical skills. Later in life, he worked as a general contractor and accumulated wealth through this work and by investing in real estate.

In 1847, William Evans entered into a contract with the City of Boston to fill in and grade a large tract of marsh land and tidal flats at the South Bay in South Boston. During that time, Boston was experiencing a large influx of immigration from Ireland due to people fleeing the potato famine. In response, the city attempted to expand the available residential land for upper-middle-class Yankees, whom they valued as taxpayers and voters, through the South Bay Lands project. The city’s goal was to encourage these residents to remain within the city rather than move to the nearby suburbs that were being developed at the time (Seasholes, 2003).

Evans’ contract also specified that he would build a sea wall and wharves, and grade Tremont Street and other streets in the southerly part of the city, as well as build a temporary railroad to transport gravel and other materials to execute the proposed work.

Figure 3: William J.R. Evans, Jr.

According to the book Gaining Ground: A History of Landmaking in Boston, Evans proved to be one of the most difficult contractors the city dealt with in the mid 19th-century, frequently failing to carry out his work, often disputing the terms of his contracts, and making numerous claims for damages (Seasholes, 2003). Despite these challenges, the city extended, renewed, and supplemented his South Bay contract in 1848, 1854, 1858, and 1859.

On November 20, 1862, the South Bay Lands project was finally complete, over 14 years after the city first contracted with Evans. His work resulted in 67 acres of new land in Boston as well as new wharves. Rather than the residential neighborhoods that the city had originally envisioned, the new land became the location of many city departments and the Boston City Hospital.

Two years prior, in 1860, William Evans’ son, William J.R. Evans (figure 3), married Ellen Seaver, both aged 22. William J.R. was working as a clerk at a crockery store in Boston at the time. Ellen Seaver was the daughter of Joshua Seaver, a prominent citizen of Jamaica Plain and the owner of the Robert Seaver & Co grocery store on Centre Street which Joshua’s father established in 1706. In an article from 1913, the Boston Daily Globe surmised that it was the oldest grocery store in Greater Boston and probably in Massachusetts. Ellen and William J.R.’s fathers served together as assessors for the City of Roxbury in 1848.

Figure 4: Tennis court at 52 South St., former location of the Evans and Spiegel house. Spiegel stable and sausage factory in the background.

The same year his son was married, William Evans purchased land from David Greenough at the corner of South Street and Carolina Avenue in Jamaica Plain. That land would become 52 South Street, where the tennis/pickleball/basketball court is currently located (figure 4), and a portion of 30 Carolina Avenue, where the stable is currently located at the Penshorn Roofing Company.

Figure 5: Inset of 1891 Bird’s Eye View Map showing the Evans and Spiegel house at 52 South St.

At 52 South Street, William Evans built a stately wooden three-story home, which can be seen in the 1891 Bird’s Eye map of Jamaica Plain (figure 5). It is possible that he built the house for his newly married son, William J.R., and his son’s wife, Ellen, who were living there by 1870 with their three children. William J.R. would reside there for the remainder of his life.

The elder William and Hepzibah Evans had lived at the corner of Lamartine and Green Streets in Jamaica Plain. But by 1880, after her husband had died, Hepzibah was sharing the 52 South Street home with her children and grandchildren.

In May 1861, shortly after the commencement of the Civil War, William Evans donated the use of his new six-story residential hotel, the Evans House, to the City of Boston. Located at 174-175 Tremont Street, across from the Boston Common, the hotel was used by the city as a hub to collect and distribute donated goods and money for soldiers and their families. It also housed returning soldiers who were sick or without a home.

Despite initially offering the Evans House at no cost to the city, in December 1861, William Evans applied for tax abatement on the grounds that the building was being used by the city. Then, in 1863, after the building was no longer being used for the benefit of soldiers, he billed the city $2,988.41 for repairs to the building, of which almost 50% was interest (Seasholes, 2003).

In 1861, William Evans made another donation to the city, this time a monetary donation of $10,000 for the construction of a hospital, the “income of which [was] to be appropriated for the benefit of persons injured in the city service. The sum was donated with the stipulation that the hospital should be located toward the southerly end of the South Bay lands” (Boston Daily Evening Transcript, 1861, p. 2). The hospital would become Boston City Hospital, the first municipal hospital in the United States. In 1996, it merged with Boston University Medical Center Hospital to form the Boston Medical Center.

In addition to his work as a contractor and manager of a residential hotel, William Evans invested extensively in real estate, including a building located at 92 Utica Street in Boston, called the Peterboro Block (likely named after his birth town). The building housed the American Water Wheel Company; John Richardson, sash, and blind manufacturer; Littlehale & Drake, sweep and fret sawers; James McDonald, cabinetmaker; and S.K. Taylor, blacksmith and machinist.

In 1869, William Evans constructed a building at the corner of Washington and Lenox Streets in Boston’s South End. It was a large one-story brick building with granite trimmings known as the Market House. The Market House contained over 100 stalls to accommodate market wagons for various kinds of businesses.

By 1869, William Evans’ son, William J.R. Evans, was working as a contractor for the railroads. He and his father both operated their general contracting business out of their office at 48 Winter Street in Boston, where William J.R. would work until 1878. The Boston City Directory indicated that the Evans father and son were “Contractors for Public Works.” After 1879, William J.R. Evans operated his business out of 92 Utica Street while also serving as the proprietor of the Evans House and Market House and engaging in real estate.

In addition to his contracting work, William J.R. Evans was civically engaged. He served on the Cochituate Water Board, and was active in the Republican party, serving frequently as a delegate at city, state, and congressional conventions. He was also a member of the legislature for several sessions early in the 1860’s; the Committee on Public Institutions in the 1870’s; the Elliot Lodge of Free Masons; and other local societies.

In 1871, Alden Bartlett of West Roxbury sold to William Evans the remainder of the land at 30 Carolina Avenue, where the brick Penshorn Roofing building is currently located. The following year, William Evans sold 30 Carolina Ave and the house at 52 South Street, to his son, William J.R. Evans, who already resided in the house.

That same year, William J.R. Evans took steps that would contribute to the transformation of Jamaica Plain and Boston. On February 20, 1872, during a meeting of the citizens of West Roxbury in a packed Town Hall, William J.R. offered a vote, on behalf of The Friends of the Annexation of West Roxbury,

[for a] committee to appear with counsel before the Legislature or a committee thereof, and favor the petition of W.J.R. Evans and others for an act authorizing the annexation of the town of West Roxbury to the city of Boston, said act being submitted to the voters of West Roxbury and Boston for their acceptance or rejection, and the sum of $500 is hereby appropriated, and the treasurer, under the direction of the selectmen, is hereby authorized to honor the same (The Boston Globe, February 21, 1872, p. 4).

The question was decided in the affirmative and the petition referred to the legislative Committee on Towns that same day.

Eight days later, William J.R. Evans withdrew the petition before the committee. It is unclear why he withdrew the petition for annexation. However, the petition may have been later refiled with the legislature as the Boston Globe reported that the legislative Committee on Towns gave a public hearing on that petition on February 18, 1873, at which time William J.R. Evans provided testimony.

[R.M. Morse, Jr. said that] the case under discussion was the first in the history of the Commonwealth in which a town, in its corporate capacity, had asked to be joined to a municipality…The town is bounded on three sides by the territory belonging to the city of Boston, and for that reason it was necessary, in order to establish a uniform grade and a proper system of drainage, that all should be under the same management. He gave, as a strong reason, the fact that the town is unable to establish a system of water supply adequate to its needs. He said that the affairs of the town could not be advantageously managed under its present plan of government…[William] J.R. Evans, one of the commissioners on the Stony brook drainage, stated the necessity for annexation from this matter of drainage, in which both the city and town were interested (The Boston Daily Globe, 1873, p. 4).

On October 7, 1873, citizens voted on the question of the annexation of Charlestown, Brighton, West Roxbury, and Brookline to Boston. William J.R. Evans canvassed that day in support of the annexation of West Roxbury. In the end, all except Brookline were annexed. The vote in West Roxbury was the largest ever recorded in the town at that time, at 1,333 total votes, 720 in favor of annexation. The Boston Daily Globe reported that in West Roxbury, “As soon as the result was announced, the wildest excitement prevailed; men thew up their hats, handkerchiefs, umbrellas, etc., and cheered lustily, and for ten minutes the Chairman could not be heard” (1873, p. 5).

On December 8, 1876, William Evans died of apoplexy (a stroke) at the age of 65 in Jamaica Plain. His wife, Hepzibah, died many years later, on December 28, 1905, from paresis (partial paralysis) at the age of 93; she was living at 320 Lamartine Street at the time of her death. Their son, William J.R. Evans, died on April 2, 1895, at the age of 58 from brain paralysis. Paralysis appears to have been caused by a genetic condition passed down from the mother’s side of the family, as another one of William and Hepzibah’s sons, Thomas W. Evans, also died at a fairly young age (56) from general paralysis.

In his will, William J.R. bequeathed to his wife, Ellen S. Evans, their home at 52 South Street. She would later sell the home to the Spiegel family.

Figure 6: August S. Spiegel

The Spiegel Family

August (or Augustus) S. Spiegel was born in Bavaria, Germany on September 23, 1835 (figure 6) to Carl Spiegel and his mother, whose name was not found in the historical record. August’s wife, Augusta (or Auguste/Sophia/Sophie) Sophia Haarer, was born in Bavaria, Germany in September 1847 to Frederick and Freda (Golden) Haarer. It is unclear when August immigrated to America; a newspaper article indicates that he immigrated in 1863, however the 1900 U.S. census states that he came over in 1841. Augusta’s immigration date is also inconsistent in the historical record, having immigrated to America in either 1851 or 1858.

When August arrived in America, he settled in New York City where he became a member of the Teutonia Lodge, a German American Masonic Lodge. By 1860, August was working as a brewer of Weiss, or white, beer, and living at 9 Elizabeth Street, New York City.

August and Augusta married in 1865 and began their married life in New York City. Together, the couple had five daughters – Minnie (or Minna) A. Spiegel, born in New York City in 1868; Anna (or Annie) L., born in New York City in 1869; Lillian (or Lillie) S., born in New York City in 1870; Frederieka (or Freda/Frieda) S., born in New York City in 1872; and Elizabeth (or Louisa/Liesel/Liesa) S., born in Massachusetts in 1873. Their eldest daughter, Minnie, died before the 1900 U.S. Census was taken.

By at least 1865, August was brewing beer at 49 Bayard Street in New York City and did so until 1877, while selling beer next door at 51 Bayard. He and his family also resided in the same building as his brewery, at 49 Bayard Street.

The 1870 census indicates that Augusta’s extended family also lived in New York City at the time, and, in fact, were next door neighbors: Christian Haarer, a butcher and retail sausage dealer; his wife Frederika; and their nine children, including sons Frederic and Henry, both butchers; and another son, Louis.

By 1880, the Spiegels moved to 121 Grand Street. By then, both August and Augusta were working as provision dealers at 49 and 121 Grand Street. Among their household members at the time were Augusta’s much younger sisters, Minnie Haarer (age 15), who worked at a bakery store, and Emma Haarer (age 13). Both had been born in New York.

In 1882, Augusta followed in her cousins’ footsteps and entered the sausage business, working as a sausage maker out of the 49 Grand Street building in New York City.

Augusta’s cousins eventually moved to Boston and continued the family sausage business. The Haarers proved to be prolific sausage manufacturers, operating multiple sausage factories in Boston in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Frederic manufactured sausages in Boston, at 123 Eliot Street (now Stuart Street), from 1880 to 1882. Then, between 1882 and 1890, he and his siblings, Henry and Louis, operated sausage manufacturing companies at 1344 and 1830 Tremont St (1882-1890) and at 143 Eliot Street (1882-1884). The 143 Eliot Street building was a four-story brick dwelling and store located between Tremont Street and Park Square in Boston, the current location of the Theatre District.

Figure 7: August S. Spiegel’s signature

Around the year 1883, the Spiegels moved to Boston. In 1884, August and his business partner, John Schaefer, took over the sausage manufacturing business from the Haarers at 143 Eliot Street (figure 7), their business being named Schaefer and Spiegel. They worked as partners at that location until sometime between 1887 and 1889, after which time the Spiegels fully took over the business. Augusta’s cousin, Henry Haarer, continued to work at 143 Eliot Street as a Clerk until his early death, in 1886, from Nephritis at age 28.

By 1887, the Spiegel family was also living in the Eliot Street building, with their German delicatessen and sausage factory on the ground floor and their living quarters above (the address of their home being 141 Eliot Street).

According to help wanted ads in the Boston Globe, the Spiegels sought out employees with German heritage, and German-language skills, to work at the delicatessen. The establishment offered lunch and sold cigars, tobacco, and tonics.

August would become a wealthy sausage manufacturer, highly respected and well-known in Boston and “connected with the leading German societies of Boston” (The Boston Post, 1903, p. 1). By 1903, August was reported to be worth $250,000, or $8,000,000 in 2022 dollars.

An 1899 Boston Globe article illustrated the wealth of the Spiegel family when it reported a fire at their home that started in a closet in the rear of the second floor. “In this large closet was stored in cedar chests all the winter clothing of Mrs. Spiegel and her three daughters, consisting of valuable furs, cloaks, and dresses, all of which were practically ruined involving a loss of between $1,000 and $1,500 [$45,000 in today’s dollars]” (p. 2).

Figure 8: 1905 map showing Augusta (Auguste) Spiegel’s properties along South St. and Carolina Ave.

In addition to operating their sausage business, the Spiegels also owned real estate in Jamaica Plain, next door to where the Evans family lived at the time, and where the Spiegels would eventually make their home. Between 1894 and 1897, the Spiegels purchased properties along South Street - between Carolina Avenue and Child Street - comprising of 70A, 70R, 72, 74R, and 76 South Street, and the property at 7 Carolina Avenue (figure 8). In November 1894, August S. Spiegel pulled two building permits to construct 76 and 74R South Street, both three-family dwellings. An announcement in the Boston Globe in 1907 indicated that at least one of the other properties was a two-apartment house and another a one-family house. Some, if not all, of their properties were rented out as residential units, and all buildings appear to still be standing today. During this time, they also purchased an empty lot of land that extended from 60 to 68 South Street.

In June of 1901, the Spiegels advertised for sale their “old-established German delicatessen store” on Eliot Street. The following year, on November 15, 1902, Ellen S. Evans sold to Augusta S. Spiegel her family’s home at 52 South Street and the lot of land at 30 Carolina Avenue.

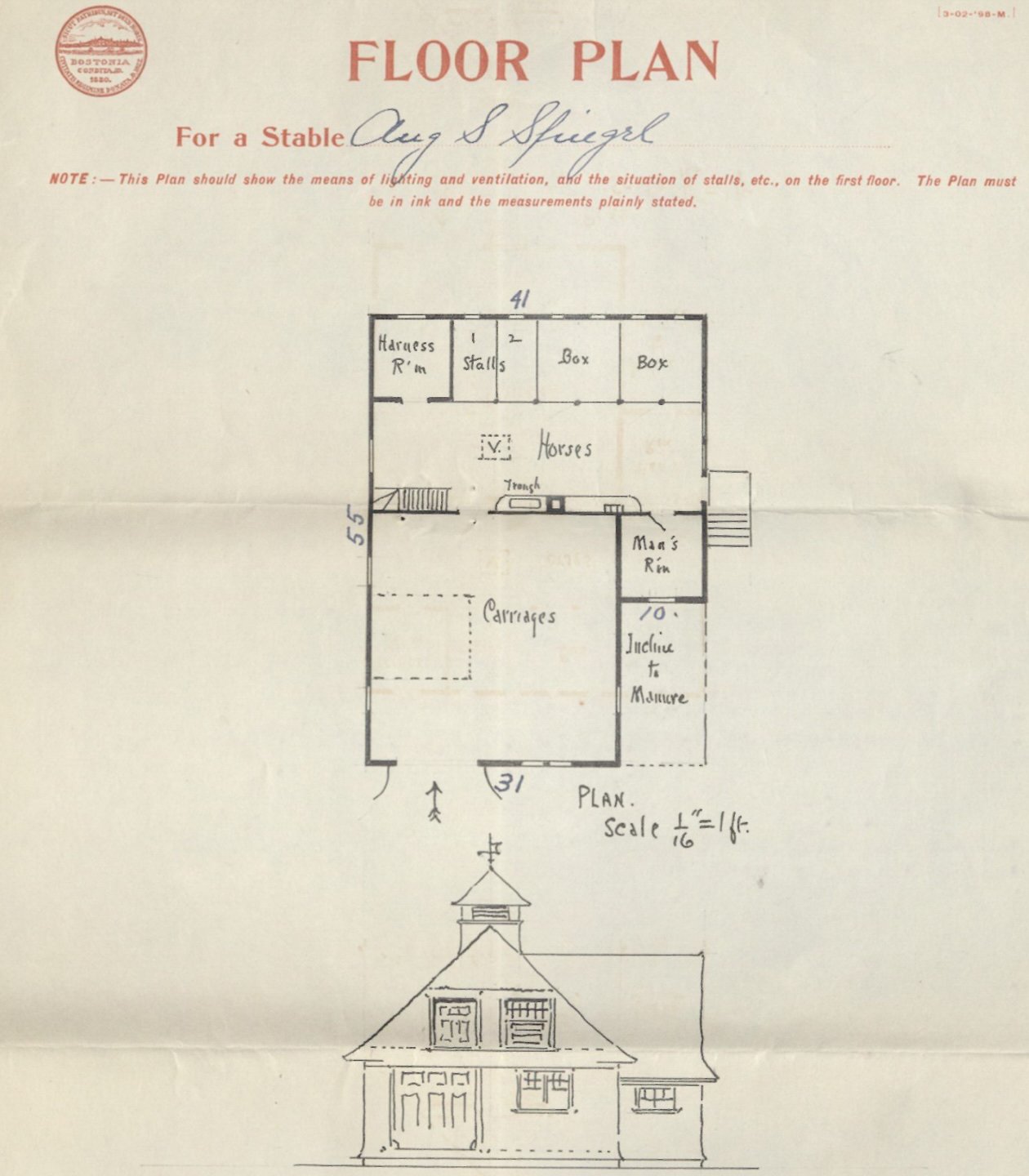

Figure 9: Floor plan and sketch of Spiegel stable at 30 Carolina Ave. (1902)

By October 1902, the Spiegels began preparing their newly acquired Jamaica Plain property for their family’s home and business needs. While still living on Eliot Street, August Spiegel filed a petition to build a private, one-and-half-story wooden stable at the Northeast Corner of Carolina Avenue and South Street to house three driving horses and carriages (figure 9). The stable also included a “man’s room to sleep and take care of the horses and the stable.” His petition was granted on November 6th. By 1906, eight horses were being housed in the stable (figure 10).

Figure 10: The Spiegel’s stable at 30 Carolina Ave.

While planning their move to Jamaica Plain, the Spiegels opened their second delicatessen, at 137 Summer Street, Boston.

Around this same time, the National Provisioner reported that “A.S. Spiegel is putting up a two-story brick building for a sausage factory on Carolina Avenue, Boston, Mass” (1903, p. 40). The success of the family business allowed the Spiegels to build a large factory on land of their own.

August Spiegel Goes Missing

In March or April of 1903, before the Spiegel’s planned move to Jamaica Plain, August Spiegel began feeling ill from acute indigestion and pains in his head. That June, his physician advised him to visit the dentist to have some affected teeth removed and a full set of dentures made to “aid digestion.” August dreaded visits to the dentist and put off similar appointments multiple times.

On Friday, June 12, Augusta woke at 5 a.m. to open the delicatessen since her husband was feeling ill. Stating that his head was bothering him and that he was going out for fresh air, he left the house at 5:30 a.m., rebuffing his wife’s advisement to stay at home.

August never returned home from his walk.

Augusta later explained to the press that August regularly took walks early in the morning, but when he did not return at his accustomed time, the family suspected that something may have happened to him, so they set out on a search. They learned that Mr. and Mrs. Davis, a married couple that lived directly across the street from the Spiegels, were looking out their window early that Friday morning when they saw August walk down the left-hand side of Eliot Street toward Tremont Street and Park Square. They were the last people to see August.

Figure 11: August S. Spiegel

To help the public aid his discovery, the newspapers reported that Mr. Spiegel was of distinguished appearance, 5’8” tall, sporting a long flowing white beard and hair (figure 11), and was wearing a brown derby, brown spring coat, and a dark suit of clothes.

By Sunday, the police could find no clues on his disappearance. The family was distraught and could not imagine where he had gone. The Boston Post reported,

The police are of the opinion that Mr. Spiegel who was suffering from pains in his head, became temporarily insane and went towards the Charles River, and it is thought he either fell or jumped in…Mr. Spiegel had no domestic troubles, having lived happily, and further, had no financial cares (1903, p.10).

The police followed up on their suspicion that August was in the Charles by dragging the river near the River Street walls but did not find him.

By Thursday, June 18, Mrs. Spiegel, confident that her husband was still alive, offered a $1,000 award for her husband to be returned home alive. Augusta expressed to the Boston Post,

Now that I have had time to think the matter over and acting on the conclusion of the Pinkerton detectives who have been working on the case since Saturday, I fully believe that Mr. Spiegel has been enticed away by some party or parties of criminals, who are keeping him in seclusion until an offer of money is made for his return (1903, p. 2).

A couple sightings were reported, one person believing they saw the sausage proprietor at 100 Blue Hill Avenue in Roxbury. The other was a reported rumor that August was seen drinking in Piscopo’s saloon on Fleet Street in the North End. Neither report was taken seriously.

On the morning of Friday, June 19, the family was delivered devastating news. Their neighbor, Edward T. Barry, found August’s body floating in the Charles River off Granby Street, between Harvard Bridge and the Cottage Farm. August had a deep gash between his eyes that was caused by either a fall or the weapon of an assailant. His clothing was intact, but the watch and chain that he usually carried were gone.

As reported in the Boston Post that Saturday,

The family are prostrated over the affair, as they cannot think of any reason that would cause the old gentleman to jump into the Charles River. They do not take kindly to the assertion that Mr. Spiegel was the victim of foul play. They simply account for his disappearance as being due to the sickness from which he suffered for three months. It was acute ingestion (1903. p. 12).

Presumably due to the wishes of his family, August Spiegel’s official cause of death was recorded as “Suicide during an attack of Melancholia.” August was 67 years old.

The Spiegels’ Sausage Factory

August’s death coincided with the construction of his family’s sausage factory at 30 Carolina Avenue in Jamaica Plain. Construction began in the spring of 1903 but had not been completed by the time August died that June.

An ad in December of 1903 stated that the Spiegels were looking for “a good reliable stableman” to work at 30 Carolina Avenue, so it is likely that Augusta and her daughters moved into their new home, next door to the factory, at 52 South Street by this time.

Figure 12: 1906 advertisement for the August S. Spiegel Company

After August’s death, Augusta Spiegel and her daughters took over the sausage business and eventually organized it as the “Aug S. Spiegel Company.” In addition to operating their new factory on Carolina Avenue (Figure 12), they continued to run their two delicatessens.

The location of the Spiegel’s new home and factory would have been extremely convenient for managing their rental properties located next door, which were still under their ownership. The front door of the factory, facing Carolina Avenue, likely led to an office where the family managed their sausage company and their rental properties. In fact, newspaper ads instructed interested tenants to apply at 30 Carolina Avenue.

Augusta Spiegel was president of the Aug S. Spiegel Company, while her daughter Lillian worked as a cashier at the Eliot Street delicatessen, her daughter Elizabeth as a cashier at the Summer Street location, and her daughter Freda as bookkeeper. Elizabeth also worked as bookkeeper at the sausage factory, according to the 1910 US Census. It is also interesting to note that Augusta’s cousin, Fred Haarer, moved to Jamaica Plain around 1889 (29 Wyman Street, 6 Wyman, 9 Brookside Avenue, and 198 Green Street) and worked as a sausage maker at 75 Shawmut Avenue. Frederick retired in 1909 and later moved to Medford.

By 1904, the Spiegels’ factory was one of two sausage factories located in Jamaica Plain, the other being operated by Erath Henry at 374 Centre Street. A 1913 business directory indicated that the Spiegels solely processed sausage; no slaughtering took place on site.

Figure 13: 1906 advertisement for the August S. Spiegel Company

The family advertised the quality of their products and the sanitary conditions of their factory in the Boston Globe (Figure 13):

Meat Products Made from Impure Ingredients are sold by many restaurants and marketmen. Insist upon proving that the sausage you eat is Spiegel’s. We take pleasure in showing you through our interesting and spotless factory at Jamaica Plain. On a sunny day our kettles sparkle like diamonds. Our products on sale everywhere (1906, pg. 7).

The State Board of Health confirmed the cleanliness of the Spiegel sausage factory in 1906 in its Monthly Bulletin, which also provided a description of the facility and its employees:

The room in which the meats are cut is properly lighted and ventilated, and is neat and clean. The floor is of cement and is properly drained. The capacious refrigerator in which the meats and finished products are stored is very clean.

The large room in which the sausages are made has good light and is ventilated by a power fan. The floor is of concrete, covered with wooden slats, and drains to a strainer. The machinery and tables are scrubbed thoroughly every night.

The employees range in age from twenty to fifty years, are intelligent and healthy in appearance, and refrain from spitting. The noonday meal, for which one hour is allowed, is not eaten in the workrooms (p.150).

Additionally, in 1914, the Board of Health reported that they found no adulteration in the Frankfurt sausage of the Spiegel Company.

In 1905, at the age of 34, Augusta’s daughter, Freda Spiegel, married meat cutter Cornelius J. Cotter, age 25. In 1907, Anna Spiegel, age 37, married William C. Brackett, age 41, who worked as an assistant at the registry of deeds within the courthouse and later as a real estate broker. The wedding took place in Augusta’s home, where the drawing room was decorated with palms, roses, and carnations for the special event. The double-ring ceremony was performed by Rev. Charles Fletcher Dole, an influential Unitarian Minister who served for 40 years as pastor of the First Congregational Church of Jamaica Plain. Dole’s son, James Drummond Dole, is known for establishing the Hawaiian Pineapple Company that would later become the Dole Food Company.

After Anna’s marriage, the couple moved in with her mother at 52 South Street, along with her sister, Elizabeth; a servant from Sweden named Augusta Anderson; and a coachman from New Jersey named Seton Haskell.

Augusta sold all her rental properties in Jamaica Plain between 1907 and 1909, as well as the large lot of land at the corner of Carolina Avenue and South Street, which was adjacent to their home. In 1909, on that empty lot, the new owner, Hyman M. Rambach, built the current one-story commercial building at 60-68 South Street to house stores. Today those storefronts are the location of Papercuts and Ferris Wheels, amongst other establishments.

The Spiegels appear to have ceased operations at their Eliot Street delicatessen in 1907. However, they continued to operate their Summer Street delicatessen and the Carolina Avenue factory.

The Spiegels also operated a sausage wagon from which they sold their products. In 1912, a 24-year-old employee that worked as a wagon driver, named Alfred Leavey, was reported to have stolen $14.90 from the company, disappearing and sending the horse and wagon back with a boy. He was later sentenced to 30 days by the West Roxbury Court.

The Spiegel family fortune took a turn the following year when an involuntary bankruptcy petition was filed on Augusta in May of 1913; the Boston Evening Transcript reported that Augusta’s liabilities were $36,170 and her assets $32,882. Her company was then placed in receivership.

Shortly thereafter, in July 1913, the Augusta S. Spiegel Estate sold the factory and their home to Joseph J. Leonard, Treasurer of the Aug. S. Spiegel Co. Two months later, Leonard sold the property back to the Aug. S. Spiegel Co. It’s not clear why these transactions took place, but it was likely to manage the family’s difficult financial situation.

On June 10, 1914, Augusta died at the age of 68 from acute dilation of the heart and nephritis, with diabetes as a contributory condition.

In September that year, the Boston Globe reported,

Elizabeth Devine has just taken title to a valuable property in West Roxbury. It is situated on the corner of South st and Carolina av, consisting of a large lot of land, which will be improved by the new owner. The grantor is Aug S. Spiegel Company (September 3, 1914, p. 12).

However, the Spiegels continued to live there and operate their sausage factory at that site. But in 1918, after 15 years of living and working in Jamaica Plain, the Spiegel family defaulted on the mortgage that covered their home and factory. Both were foreclosed on and sold at auction on August 13th. The highest bidder was Arthur J. Caulfield of Brookline who purchased the properties for $1,760.

But the family business continued elsewhere. In 1920, Elizabeth Spiegel married Kurt Johannes Werner. Werner immigrated from Germany in 1914 and had worked at the Spiegel’s Summer Street delicatessen as a clerk and manager since 1917, where the couple likely met. Together the couple ran the family sausage business under the name of the Spiegel Corporation, with Elizabeth as president and saleswoman and Kurt as treasurer and proprietor. The couple continued to operate their Summer Street delicatessen and opened a new delicatessen at 104 Canal Street in 1921, while living at 78 Peterborough Street, Boston and later 165 Perham Street and 81 Vermont Street, West Roxbury.

The last reference to the 137 Summer Street delicatessen or the Spiegel Corporation in the city directories was in 1946, indicating that the Spiegel family sausage business ended 61 years after it was started by August and Augusta in 1885.

After the Spiegels

An April 1944 City of Boston Departmental Communication described the Evans’ and Spiegels’ former home at 52 South Street, which was last being used as a single-family home:

This is a large, vacant dwelling of wood construction. It is well boarded up and apparently in sound structural condition as a whole. At the moment children are destroying the entrance porches which are large and high, and have left them in an unsafe condition. The children have pried open a basement window which is now open to trespass. I recommend that the porches be razed or made safe and the cellar window be boarded up to keep out trespassers.

The house was razed by the city that May. By 1954, the Rodick Company built a gas station at that site. Today it is the site of the tennis court and square, called John W. Murphy Square and the South Street Mall & Courts.

Sometime between 1918 and 1921, Joseph L. Griffin opened a dairy at the Spiegel’s former sausage factory at 30 Carolina Avenue, where he pasteurized, bottled, and delivered milk for retail house delivery, and for schools. After Griffin’s death in 1955, his sons ran the business for a short time, and then went out of business. The building sat vacant for a time when it was purchased by Everett F. Penshorn in 1960 for his retail roofing business, which was established in 1894, and continues to operate at that site today.

By Jenny Nathans

March 17, 2022

Sources

Ancestry.com

Boston City Directories

Boston Inspectional Services

City of Boston Archives

Genealogical and Personal Memoirs Relating to the Families of the State of Massachusetts, edited by William Richard Cutter, A.M., Lewis Historical Publishing Company, 1910.

Jamaica Plain Historical Society

“Local and Personal.” The National Provisioner, vol. XXVIII, no. 19, 1903, p. 40.

Newspapers.com

Norfolk Registry of Deeds

Norman B. Leventhal Map and Education Center – Boston Public Library

Seasholes, N.S. (2018) Gaining Ground: A History of Landmaking in Boston. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press.

State Board of Health. “The Slaughterhouses, Packing Establishments and Sausage Factories of Massachusetts.” Monthly Bulletin of the State Board of Health of Massachusetts, vol 1, no. 6, 1906, p. 150.

Suffolk Registry of Deeds

Figures

(1, 2, 4, and 10) Photographs by Jenny Nathans

(3) Ancestry.com, public member photo from Barb Coyle, shared on January 11, 2019

• Photograph of William J.R. Evans, Jr.

(5) Norman B. Leventhal Map Center Collection, Boston Public Library

• 1891 Bird’s eye map

(6) Boston Globe, June 19, 1903, page 4

• Photograph of August S. Spiegel

(7 and 9) Courtesy of the City of Boston Archives

• August S. Spiegel’s signature

• Floor plan and sketch of stable

(8) Jamaica Plain Historical Society, Bromley Atlas of Boston

• 1905 map

(11) Boston Post, June 19, 1903, page 2

• Drawing of August S. Spiegel

(12) Boston Globe, June 23, 1906, p.8.

• Advertisement of A.S. Spiegel

(13) Boston Globe, June 20, 1906, page 8

• Advertisement of A.S. Spiegel