The History of 48 Rockview Street and the Fisher-Bang Family

“I was introduced to Joyce “Joy” Fisher by a mutual friend who knew I loved Jamaica Plain history, especially the history of houses and the people that lived in them. Joy and I met for the first time in November 2021 to talk about the history of her family. From then on, I visited her every Monday at her house to kibbitz about history and our lives, and most importantly, to bake! The following article is part oral history and part research from primary sources, including publicly available records and Joy’s personal family collection. It is also a labor of love and a way to honor my friend whom I will miss dearly.”

Joyce “Joy” Fisher

Architecture of 48 Rockview Street

48 Rockview Street

At the apex of the hill that is Rockview Street in Jamaica Plain is the home of Joyce “Joy” Fisher, a life-long resident of the neighborhood. Joy began her life at the house at 48 Rockview Street. Though modest in appearance from behind tall bushes, Joy’s house has unusual architectural features. It also contains an exquisite mural painted by her grandfather, a German muralist and interior decorator, who lived next door.

Watercolor of 48 Rockview St. Painted by either Frederick Bang or Nora (Bang) Fisher

48 Rockview Street is a single-family house that was built in 1930 for Joy’s parents, Nora K. (Bang) Fisher and Dana W. Fisher, Jr. (pictured below). The 1 ½-story house is a fully intact example of a high style Colonial Revival, full Cape. The architect and contractor for the house was Frank Fryer of 1175 East Street in Dedham, Massachusetts. As Joy explained, the house was designed to resemble a house that the designer built in East Dedham.

Nora (Bang) Fisher

Dana W. Fisher, Jr.

Classical Revival features include the narrow pilasters and broken pediment around the front door of the portico. Above the door is also a transom with four bullseye lights. The two dormers on the front of the house are topped with simple pediments. The molded box cornice has partial returns across the gable ends, suggesting the shape of a Classical pediment.

Quoining and fir tree cut-outs

Rather than having simple corner boards, there is quoining on the front two corners of the house, a very unusual element for a 1930’s Cape. The house retains its original twelve-over-twelve double-hung sash windows. A few windows also retain their original two-over-two wooden storm windows. The remaining original storm windows are being stored in the basement of the house. Pintels remain on some of the windows where shutters once hung. The windows on the front of the house are flanked with shutters that have cutouts of fir trees, an unusual detail for a high-style design

Side elevation of 48 Rockview Street

The windows on the second floor of the house, on the side elevations, have slightly projecting frames, which can be seen at the band molding around the edges of the windows. Projecting frames are typically an indication of an 18th century or early 19th century plank-construction, rather than the post-1830’s balloon construction. In plank construction, the planks did not allow for sufficient depth for a window to be recessed within the wall, which would cause the windows to project. The design of 48 Rockview Street imitates that pre-1830’s feature. Finally, beneath the gable sits a small and narrow 8-light attic window. The foundation of the house is constructed with concrete block, and the roof has always been covered with asphalt shingles.

Embossed figure over vestibule doorway

The interior of the house also invokes Classical elements, including three embossed figures above the doors and windows of the front vestibule (one pictured here, the rest in the accompanying Photo Gallery). It is likely that those figures were created by Joy’s grandfather, Frederick Marcus Bang. Bang was a muralist who drew on Classical images in his work. Along the ceiling of the large living room is molded trim. At each end of the room is a single herald on each wall. The stained wood and brick fireplace is Colonial Revival in style with pilasters and a broad lintel.

The formal dining room includes crown molding, wainscoting, and a built-in cabinet. The most striking feature of the house can also be found in this room: all four walls are decorated with a hand-painted mural of a landscape. The mural features hills, flowers, trees and clouds, a bridge spanning a river, a castle atop a hill with a village below, Classical Greek architecture, and a statue and fountain, also of Classical design. The mural was painted by Frederick Marcus Bang, a professional fresco painter and interior designer from Germany. Bang was the father of Nora K. (Bang) Fisher, the original owner of the house, and the grandfather of Joy Fisher. Frederick Bang lived next door to the Fishers at 44 Rockview Street and painted the mural in his daughter’s house shortly after it was built.

Scene from Frederick Bang's mural in the dining room

Joy shared her admiration of her grandfather’s artistry:

Scene from Frederick Bang's mural in the dining room

“What’s interesting about the dining room is that each of the panels stand by itself. They are all very different scenes. The one that you see that is close to the built-in cabinet, it’s sort of, to me, a combination of the Rhine River and a castle. In the background it looks so very New England, with church steeples and barns and things like that. On another, is a cottage next to a stream with flowers in front that looks very English. When I stop to think about the creativity that my grandfather put into that, and they are all linked together over the tops of the windows by sky, the painted sky. He was a genius.”

Frederick died when Joy was only five years old. But she remembers her artist grandfather in 1944, shortly before he died, looking around the dining room and saying, “I think this needs a little bit of touch-up,” and then him taking up his palate and paint brush and enhancing some of the colors. In contrast to the formal living and dining room, the design of the kitchen is less ornate. The ceiling of the kitchen has a simple trim, and the door surrounds are flat. The contrast in the design of the rooms creates a separation between the social and the utilitarian, the public rooms for entertaining and the private workspace.

The back of 48 Rockview Street (with enclosed porch)

The upstairs bedrooms have crown molding, and the small den has its original glass doorknobs and a built-in bookshelf. At the top of the staircase are shallow shapes simulating a balustrade and newel posts. The only major alteration made to the house since its construction was the addition of an enclosed back porch in 1939. Dana W. Fisher, Jr. drafted the original design of the porch, followed by a detailed blueprint from architect Myer Louis of 73 Cornhill, Boston. The porch also appears to have retained its original features, including the latticework at its base. A minor alteration was made to the steps leading to the front door of the house. Originally, they were made of bricks, placed in a half-moon shape. But eventually the steps started to crumble, so Nora Fisher replaced them with the current stoop.

Joy especially enjoyed the beautiful view from her home. She loved to look out the back window of her living room while sitting at her computer. The window looks out over a “wonderful yard” at Chestnut Place and a “wild expanse of open space that the turkeys love, and the rabbits go to, and all this wonderful wildlife.”

Frederick Marcus Bang and Anna (Olsen) Bang

Joy’s maternal grandfather, Friedrich “Frederick”/ “Fredric” Marcus Bang [Footnote 1], was born in the “Toll House” in the municipality of Klixbüll. This town is in the state of Schleswig-Holstein, Germany. Fredrick was born on April 23, 1867 to Jüergen “Carl” Christian Bang and Catharina “Christine” (Jüergensen) Bang. As shared with this author by the Mayor of Klixbüll, Werner Schweizer, Fredrick’s birthplace, the Toll House (or Customs House) was located west of the B-5 Road between Klixbüll and the small city of Niebuell. German archives indicate that Fredrick’s father worked as a “Sattler/Sattelmacher” (saddler), and later as a “Chauseebaumpächter/Chausseeeinnehmer,” which is a “sort of cashpoint officer to take the fees for the use of a developed country road” (Bettina Dioum, email, 2022). This would explain why Fredrick was born in a toll house – his father was the toll collector! The Toll House was demolished around 1960.

This author is unaware of how many siblings Frederick had, but his birth and baptism records indicate that he may have had at least two sisters, Cathrine Magdalene, born in 1863, and Catharina Maria, born in 1865. After living in London, England, Frederick immigrated to the United States at age 32, sailing in the S.S. Ivernia from Liverpool on April 9, 1901, and arriving in the port of Boston on May 9, 1901. It was his first time in the United States. Frederick’s immigration records indicate that he practiced as a professional decorator while living in Germany. A sketchbook, dated 1884, shows that he was either studying to be, or practicing as, an interior decorator by age 17. It is also possible that he used the sketchbook during his travels around Europe. Joy Fisher explained that Frederick’s family paid for him to tour Europe to study the great artists.

Frederick and Anna Bang

At age 33, Frederick married Anna Otilie (Olsen/Ohlsen) Anderson, age 25, on March 10, 1902, in Roxbury, Massachusetts. It was Frederick’s first marriage, and Anna’s second, her first spouse having died young. At the time of their marriage, Frederick was living at 7 Shawmut St., Boston and was working as a “painter.” Anna was living in Winchendon and worked as a tailoress. Joy’s maternal grandmother, Anna, was born in Oslo, Norway on October 4, 1876 to Jonette Paulsen (born in Norway) and Anders Magnus Olsson (born in Sweden), in the neighborhood called Bislet. Anna was the second of five children, all born in Oslo (called Kristiania at the time): Birthe Mathilde Palma Olsen (“Mathilde”), Anna, Olaf Olsen, Nora Franceska Olsen, and Magda Josefine Olsen.

On October 22, 1899, at age 23, Anna married Ole Anton Anderson in Norway. However, Ole appears to have died no more than a year later, at age 21. Anna immigrated to the U.S. on September 20, 1900, at the age of 23. “Anna Anderson” is included in a list of passengers who were immigrants traveling in the S.S. New England that sailed from Liverpool to Boston, arriving on October 5, 1900. Her stated destination was the home of her uncle, August Hoffstett, in Winchendon. She had last been in the United States in 1895.

Anna’s brother and sister, Olaf and Mathilde, also immigrated to the United States. In 1903, Olaf lived at 274 Centre Street, Jamaica Plain, at the same home as his sister, Anna, and her husband Frederick Bang. On February 23rd of that year, Frederick and Anna’s daughter, and only child, Nora Anna Katharina Bang, was born. Two days later, on February 25, Olaf married Thea Mathilde Antonsdatter Braaten. Olaf’s sister, Mathilde, had married Thea’s brother, Karl Johan Antonsen Schjoberg, in 1898 in Oslo. Thus, brother and sister married a brother and sister! In Norwegian, the term for grandmother is “Bestemor,” which is how Joy referred to her grandmother, Anna. Though the Norwegian word for grandfather is “Bestefar,” Joy always called her grandfather, Frederick, “Bestapapa” because her mother called him Papa. Joy described her Bestemor:

“She was absolutely exquisite. She was very spoiled because she was so beautiful, and because she was so petite at 4’11”, people just wanted to take care of her. According to my mother, she could have been a ballerina she was so graceful. She was also a fabulous skier. She came to the United States initially when she was 18. To me it is so extraordinary, a young girl coming from Norway who had no English, could come into New York, and make her way to Wisconsin to her grandmother’s; how does that happen? To the best of my knowledge [she came on her own]. She returned to Norway and married, but her husband died. She came back to America [in her early 20’s]. Somehow, she came back to Massachusetts, and she met my grandfather in Western Massachusetts.”

This crocheted white bedspread is Anna’s work

Anna was a seamstress by profession and an artist in her own right. She created exquisite inlays of lace and other delicate works. From at least 1903 until 1905, the Bangs lived at 274 Centre St., Jamaica Plain. From 1906 to 1909, the family lived at 100 Wyman Street. A postcard written to Frederick Bang indicates that they lived on Wyman Street in 1913; however, other historical records document that they resided at 51 Boylston Street from 1910 to 1916, so the location of their residence during that time is unclear. It is possible that the postcard was mistakenly mailed to an old address. In 1917 the family moved to 62 Jamaica Street, where they lived until 1924. In 1915, at the age of 48, Frederick applied for citizenship. His Declaration of Intent indicated that he was 5’9”, 152 lbs., and had gray hair and gray eyes. His application for citizenship was denied the following year because his Declaration of Intention lapsed before his Petition for Naturalization was filed. In 1917, the Bangs moved to 62 Jamaica Street in Jamaica Plain. That same year their daughter, Nora, graduated junior high from the Bowditch School. On February 28, 1921, Frederick finally became a U.S. citizen.

By at least 1904, Frederick Bang was working as a fresco painter in Boston. The 1910 U.S. census also indicates that he worked as a house decorator; the 1920 census said he worked as a painter for a “shop”; and the 1930 census stated that he was an interior decorator. Frederick Bang worked for the well-known Boston-based decorating agency Sofus L. Mortensen, Co. During his tenure with Mortensen, including at least during the 1920’s and 30’s, Bang decorated the interiors of churches, including St. Julia’s Church in Weston, Immaculate Conception Church in Easthampton, and St. Catherine of Siena Church in Charlestown. Bang’s artistry can be seen in the drawings/paintings of church interiors that Bang created for his work with Mortensen’s agency.

Frederick Bang's sketch of proposed interior decorations for St. Julia's Church, Weston, MA

Frederick Bang's mural at St. Catherine of Siena Church, 1922, as published in the Boston Globe

On September 2, 1922, the Boston Globe reported that artist “F. Bang” painted the interior of the church St. Catherine of Siena in Charlestown, Mass., under the direction of Sofus L. Mortensen, mural decorator. The article stated that Bang was “one of the most noted [muralists] in the country” (Boston Globe, 1922, p.16). St. Catherine opened in 1887 and closed in 2006 when the Boston Archdiocese sold its buildings. The church still stands, with a Dollar Tree store operating in the basement level. It is unknown to this author whether the mural still remains in the interior of the church as she has not yet succeeded in making contact with the owners to visit the inside of the church.

Frederick Bang was also a highly skilled fine art painter and woodworker. Examples of his work are displayed around the house at 48 Rockview Street, including paintings on canvas and on wooden and metal trays, a bookshelf, and dollhouse furniture (see Photo Gallery). As Joy explained in a 2009 oral history documented by youth in the Peace Drum Project:

“When I was growing up during World War II they didn’t have great dollhouse furniture like they do now. My grandfather who was an artist made me all kinds of furniture. He made a couch, a stove, a sink, and all of these wonderful things for my dollhouse” (Peace Drum Project, p. 13).

In addition to his love of art, Joy recalls that her grandfather loved gardening. She can also remember her mother, Nora (Bang) Fisher, telling her that he would go to the Arnold Arboretum and pick the grapes from the vines, and bring them home to make wine. Frederick and Anna Bang traveled often, including voyaging in cargo ships with a limited number of passenger rooms. Joy states, “It certainly wasn’t glamourous in any way, but they would get to see different parts of the world.” Anna also went home to Norway every two years, “except for during the war.” A passenger list shows that Anna, age 38, and Nora, age 11, sailed from Bergen, Norway to New York City in the S.S. Bergensfjord on August 29 to September 7, 1914, returning from a trip to visit Anna’s father, who lived at 62 Pilestredet in Oslo. Joy explained that during that trip her mother and grandmother had trouble finding return passage because of the outbreak of World War I. Nora sailed to Oslo again in the summer of 1926, this time on her own.

44 Rockview Street (2023)

In 1924, Frederick and Anna purchased and moved into 44 Rockview Street, Jamaica Plain a two-story frame house which still stands next to Joy’s house at 48 Rockview Street. The Bangs changed the occupancy of the 44 Rockview Street house from a single-family to a two-family home. On October 8, 1930, James J. Long and Olive May Long of Boston, sold to Frederick and Anna Bang lots D and C1 on Bates & Chellman’s plan of land drawn up on September 5, 1930. This property was 48 Rockview Street. The Bangs purchased the land for their daughter and son-in-law. The property contained 14,042 square feet of land and included a barn. The property was located directly next door to the Bangs’ home at 44 Rockview. Almost two weeks later, on October 20th, the Bangs sold 48 Rockview Street to their daughter, Nora K. (Bang) Fisher and their son-in-law, Dana W. Fisher, Jr.

1930 land plan of 44/48 Rockview lots

Blueprint of 48 Rockview St. From the Boston City Archives

On November 3rd of that year, Dana and Nora Fisher filled out an application to build a two-story, single-family home at 48 Rockview Street. The Boston City Archives and Joy Fisher own the original blueprints of the house. In 1932, Fredrick and Nora sailed in the ship S.S. Reliance to Hamburg, Germany. It is unclear whether they traveled there for a vacation or to visit Fredrick’s family. Frederick Bang appears to have retired either in 1935 or 1940, the year he filed his application for Social Security benefits. He died on November 13, 1944, at 44 Rockview Street, at the age of 77. Anna K. (Olsen) Bang died on March 29, 1960, in Foxborough, Massachusetts, at the age of 84. Her cause of death was pulmonary thrombosis. Her medical condition was coronary sclerosis. 48 Rockview Street remained in the Fisher/Bang family, and Joy Fisher resided there, until she passed away in January 2023.

Dana Walker Fisher, Sr. and Edith George (Tweedy) Fisher

Learn more about Joy’s Fisher ancestors from Mansfield, MA in a supplemental article here.

Joy’s paternal grandparents Dana Sr. and Edith Fisher lived in Mansfield until 1900, at which time they moved to 17 Akron Street in Boston. On October 23, 1900, Dana Sr. joined the Boston Police Department as a reserve officer in Division 2, at the Milk Street station. On May 16, 1901, he was appointed as a patrolman at the same station. On January 21, 1904, Dana Sr. and Edith had their first child, Dana Walker Fisher, Jr. (Joy’s father).

Being a police officer in a major city, Dana Fisher, Sr. was frequently in the newspaper. The Boston Globe reported on one of his adventures from October 27, 1906: At 2:15 a.m., while working the “house route,” the beat that included Newspaper Row in downtown Boston and extended as far as Franklin Street, a watchman from the Elevated Railway ran up to Patrolman Fisher and told him that he heard the crash of glass near Franklin Street. Fisher ran to 388 Washington Street, at the corner of Washington and Franklin Streets, the location of the clothing and men’s furnishing store of William H. Richardson & Co., and found that a large plate-glass window had been broken. Seeing no one in the store, Fisher ran to Summer Street and saw a man going towards South Station with a bundle of clothing in his arms. Fisher ran to the man, seized him, and found that the man was holding three heavy winter coats with William H. Richardson, Co. price tags on them, valued at $135. “Fisher pulled the prisoner back to the store, making the prisoner carry the overcoats” (Boston Globe, 1906, p. 5). The suspect, later identified as 28-year-old Daniel Moynihan, claimed that he broke into the store because he had a grudge against the store he robbed, a story the police did not believe.

On May 12, 1909, the Boston Globe published a comical story of another arrest made by Dana Fisher, Sr., which is re-printed in full here:

“Thomas Cashman of Roxbury was taken from the seat of a watering cart by patrolman Dana W. Fisher of the Court-sq station and locked up on a charge of intoxication this morning. As he stood before the desk it was a physical impossibility for him to give coherent utterance to his thoughts. He insisted on everybody having “jus’ nuther little drink.”

Pedestrians and storekeepers on Tremont Street were the first to observe the condition of Cashman. As he drove down Tremont st toward Beacon st about 10:35 the reins were drooping and the horses attached to the water wagon were apparently trying to cut out a figure eight on the asphalt. Tossing about on his seat, his face beaming with smiles, Cashman looked happy. Down near the crossing at Beacon st stood patrolman Fisher, and he approached the watering cart. Cashman had by that time consumed more than is ordinarily required in covering any fixed distance and the street was deluged. Fisher grabbed the horses by the bridle and shouted at the driver. Cashman tried to drive on, paying no heed to the boys on the sidewalk, who were inquiring whether he fell off the water wagon.

Believing that the reins should be in firmer hands, patrolman Fisher mounted the seat of the wagon and relieved Cashman, who placed his arms around the neck of the patrolman while the latter drove. People on the sidewalk and in the office buildings were convulsed. Down Tremont st. to Scollay Sq, thence to Court st, Fisher drove the water wagon, and by the time the vehicle turned into Court sq there were several hundred persons in its wake. Cashman’s little time this morning, according to the police, temporarily raised havoc with traffic on Tremont st. Teamsters and chauffeurs were at their wits’ end, while pedestrians took no chances in crossing the street” (Boston Globe, 1909, p. 9).

By 1908, Dana Fisher, Sr., Edith Fisher, and Dana Fisher, Jr. moved to 26 Walk Hill Street in Jamaica Plain. Dana Sr. and Edith lived there until Dana Sr.’s retirement in 1933.

On May 30, 1912, Dana Sr. was promoted to the rank of sergeant and transferred to the Roxbury Crossing station in Division 10. Joy recounts that when working double shifts at Roxbury Crossing, her grandfather would write postcards to her grandmother. Since there were two deliveries of mail per day at that time, her grandmother would receive a postcard from her husband that he had written in the morning, saying that he was working a double shift and would not be home for dinner. On May 2, 1919, Fisher served with his fellow Roxbury Crossing police officers in a big police detail outside the courthouse, in the aftermath of the May Day Riots of the “Boston Revolutionists.” During the riots in Boston, scores of people were injured from knives and bullets. In the end, 113 were arrested, and from that group, 103 men and women were arraigned.

On July 11, 1922, Dana Sr. was promoted from sergeant to lieutenant and assigned to Division 17 in West Roxbury. In 1924, he qualified as a sharpshooter, and in 1926, as a pistol marksman. By 1927, Dana Sr. was a member of the Boston Police Department’s riot squad; he served in the 8th company as Riot Gun No. 2. On January 17, 1930, Dana Sr. took an examination at the State House before the Civil Service Commission to be promoted to the grade of captain, but he does not appear to have achieved that position. Dana Sr.’s adventures were not limited to the workforce. He made the newspaper again when on March 14, 1932, he was one of 87 passengers bound from Boston to Bermuda in the Canadian National Steamship, Prince David, when it struck two coral reefs twelve miles off St. George’s, Bermuda during a blinding rainstorm. He and the others on the “floating palace” had no chance to collect their baggage before they climbed into lifeboats and were lowered into the rough seas. The passengers rowed for an hour and half before reaching the ship Lady Somers, while the Price David sank behind them. In 1933, Dana Sr. retired from the Boston Police Department. After retirement, he and Edith moved back to Mansfield, into the house that Dana Sr.’s father had built at 25 Fisher Lane. Dana W. Fisher, Sr. died on February 15, 1940, at age 68, at his home in Mansfield. Edith G. (Tweedy) Fisher died on April 18, 1958, at age 84, also in Mansfield.

Dana Walker Fisher, Jr. and Nora (Bang) Fisher

Dana Walker Fisher Jr.

Joy’s father, Dana Walker Fisher, Jr. was born on January 21, 1904, in Mansfield, Massachusetts to Dana W. Fisher Sr. and Edith George (Tweedy) Fisher. “At that time, there was a cartoonist named Bud Fisher, so people used to call my father Bud” (Peace Drum Project, p. 12).

Dana Jr.’s brother, his only sibling, was named Malcom “Mac” Grover, who was six years his junior. Mac worked for the railroad sorting mail while on the train between New York and Boston. “The job of the railway mail was to sort it before getting to the Boston post office. On June 22, 1917, Dana W. Fisher, Jr. graduated from the Francis Parkman School in Jamaica Plain. That same year, his future wife, Nora Bang, graduated junior high from the Bowditch School. In 1921, Dana Jr. graduated from English High School, where he was on the football team.

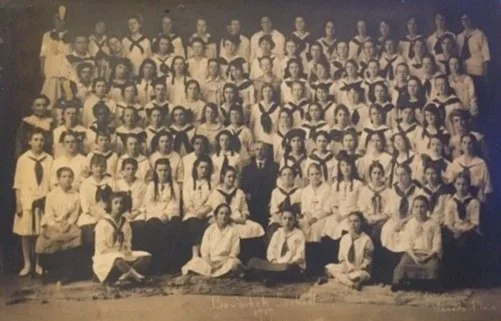

Bowditch School, junior high school class of 1917. Nora (Bang) Fisher is in the top row, fourth from the left

English High School football team, circa 1919. Dana W. Fisher, Jr., first row, second from the left

Nora (Bang) Fisher

Joy’s mother, Nora Anna Katharina Bang was born on February 23, 1903, at 274 Centre Street in Jamaica Plain. She lived there until she was seven years old. Joy explains that when her mother was young, she dated a boy that called her “Bing Bang”. The nickname caught on after she married, so everyone referred to her mother as “Bing.” Between 1910 and 1916, Nora lived with her family at 51 Boylston Street, Jamaica Plain. And from 1917 to 1924, she and her family lived at 62 Jamaica Street, Jamaica Plain.

Nora Bang studied art for four years in college, which Joy believes was the College of Practical Arts and Letters, in Boston. Nora earned her degree around 1924. Joy explains that it was very unusual back in the early 1900’s for a woman to earn a 4-year degree. Her mother used to tell her that “to be an artist, you had to be exceptional, you couldn’t just be ordinary.” Her mother did not believe herself to be an exceptional artist, so she did not pursue a career in art, but samples of her artwork can be found around Joy’s home. Nora Bang lived with her parents at 44 Rockview Street from 1924 until 1930, the year before she married. Joy believes her mother and father met when they were in their teens and her mother was living on Jamaica Street, near St. Thomas Aquinas Church:

“She met a friend who also lived on Jamaica Street who was dating my father’s best friend who lived up in the Forest Hills Cemetery, because his father was a cemetery worker. I don’t know what happened in the interim years because my mother went to art school and graduated after four years, around 1924. But they didn’t marry until she was in her late 20’s. I don’t know what the relationship was during those interim years.”

Nora Bang and Dana Fisher, Jr. wed on March 10, 1931, at the Longwood Towers in Brookline. The newlyweds took an extended honeymoon in New York, Atlantic City, and Washington. The census taken the month before Nora and Dana Jr. were married indicates that Nora, age 27, was living with her parents at 44 Rockview Street, while Dana, age 26, was living with his parents, his brother, and his Aunt Helen Tweedy, at 26 Walk Hill Street, Jamaica Plain. At that time, Dana Jr., was working as a telephone installer and Nora was working as a clerk for an automobile company.

Dana W. Fisher, Jr. (third from left) at the New England Telephone Company

On October 27, 1931, Nora’s parents granted the newlyweds the land at 48 Rockview Street. On November 3, 1931, Dana Jr. and Nora had their house built at that site. The couple would live there the remainder of their lives. By 1931 until at least 1934, Dana Jr. worked as a floor switchman at the New England Telephone and Telegraph Company located at 26 Waverly Street, Roxbury (now the location of Verizon). In September 1935, Dana Jr. passed the Massachusetts Bar. On October 16, 1935, he was admitted to practice as an attorney by the Supreme Judicial Court at Boston. On August 2, 1939, Dana Jr. and Nora’s daughter, Joyce, was born.

By 1940, Dana Jr. worked as either a supervisor or maintenance man at the New England Telephone Company, and by 1948, he was working as an instructor there.

Joy remembers her parents fondly, their love, and humor, and the challenges they faced:

“My parents were fabulous. [My father] liked to tinker with his car and read the paper. I think there was a time when he read three or four newspapers a day. He would have dinner, then he would come to the living room, and he would read until he fell asleep under the papers. He did some gardening. He was not overly enthusiastic about it, but he did it because I think that the idea of fresh produce was so appealing. He also enjoyed going to the beach. My dad was not demonstrative in any way, but I somehow instinctively knew he loved me.

My father [went to law school] and passed the bar on the first try, even while he was working full-time, day and night. [My mother said] that she did all the research. She ran around, and drove to all the law libraries. She’d look up the cases and write them out for him. She was the wind beneath his wings.

My mother was incredible, was just the most wonderful parent, which you can see in the love she put into the things she created for me. She was a fabulous seamstress; she made me a lot of my clothes. Money was very tight because my father was an [compulsive] gambler. She made me these gorgeous smock dresses and just a lovely wardrobe for a young child.

I am not sure how old I was, but it was a summer day and although there were a lot of children in the neighborhood, there was no one around. I said to my mother “I’m bored,” and she took a newspaper, and at that time the ads were silhouettes of women modeling clothes, and she copied one and traced it onto cardboard and she made me a paper doll. She handed me the paper doll and said, ‘Create a wardrobe,’ and I created a wardrobe. It was the best gift that anyone can give you because you are saying to someone ‘Be creative.’ [I made a wardrobe out of paper], just like a paper doll.

My mother was very much a stay-home mom. I remember her sewing, cooking, baking, and knitting. When I went to school, during kindergarten through third grade, I would come home at lunch. Of course, my favorite lunches were a toasted cheese sandwich and Campbell’s Vegetable Soup.

On West Street [in Downtown Boston] there was a candy shop of great renown called Bailey’s. Bailey’s sold candy by the piece. My mother would go in, and she would buy a box of chocolate candy, and she got to pick out the assortment. I would stand there with my face placed against the glass, and the salesperson would give me a piece of chocolate. They were also very famous for their ice cream, which they served in pewter cups that had a handle, with fudge sauce and whipped cream. It was very old fashioned and had a marble-top ice cream counter. And chairs had curly Q backgrounds. Very typical old Boston. Charming, absolutely delightful.

My mother was very proud that she made a hand painted sign [to hang on the tree outside our house], a ‘No trespassing’ sign to prevent people from going through the driveway and thinking it was a shortcut to Chestnut Avenue. And she was so proud of the sign, but instead of [it] saying ‘No Trespassing’ [it accidently] said ‘No Tressassing’.

[My family was not religious]. I can distinctly remember the minister from Central Congregational Church coming up, and he was a very pompous man, and encouraging my mother to come to church. And I remember saying, ‘Daddy can’t come to church because he doesn’t have a new hat.’ I might have been 4 or 5 at the time. I think that was the joke. My mother might have said to him ‘Dana, we really should go to church, I want Joy to have some religious affiliation’ and Daddy saying, ‘Well, I can’t go because I don’t have a new hat.’ So, it was kind of joke. [So, I repeated it] thinking it was the truth. I think that my mother’s father was probably an atheist. But I think my mother showed a lot of wisdom in encouraging me to go to Sunday school because she felt it would be in my best interest and leaving it up to me to make a decision as far as religion. I think that my father’s family was not overly religious but were more of a regular church-going family.

One of the nicest memories I have is thinking back to Sundays. Stores were not open, there was nothing open on Sundays. Even though my mother was not overly religious, I do remember that she would not allow me to go to the movies on Sunday. So, I remember Sunday afternoons there was this big old console radio that sat over in that corner of the room. I would sit up with my back against it, and Daddy would sit there reading the paper, and my mother would sit here knitting, and we would just listen to the radio. It was just family. And on Sundays, my mother would always do a Sunday dinner. [My Bestemor, or grandmother,] would come over from next door to have Sunday dinner with us.

Nora working in an office later in life

It became clear, when I was about 12 or 13, that my father was starting to show signs of Huntington’s chorea, which runs in families and can be passed down. (His father and grandmother had it as well.) I am fortunate that I did not get the genes. My father had worked for New England Telephone for 27 years and was forced into early retirement [because of the disease]. My mother had to go and try to find work. Because she had gone to art school, she didn’t have any really good clerical skills, so it was really hard for her to find anything that paid well. So, she ended up working for the telephone company as a cafeteria worker, and eventually was able to find a job with Westinghouse Electric as a substitute switchboard operator. [Later she learned office skills and worked in offices until she retired] .

My father then had lung cancer and was hospitalized first at City Hospital and then at Holy Ghost Hospital over at Cambridge. During that time, my grandmother, who lived next door, was suffering from, what we called at that time ‘hardening of the arteries,’ but what we now know is dementia. I would come home from school, and I would have to bring Bestemor over to the house. My mother, after working a full day, would go first to City Hospital when Daddy was there, and then come home about 7 o’clock and have to prepare a meal for a bratty 14-year-old and her mother with mental impairments. She never complained, and I don’t think she missed a night seeing Daddy in the hospital.”

Dana W. Fisher, Jr. died on April 26, 1954, at age 50, of lung cancer, while living at 48 Rockview Street. Nora K. (Bang) Fisher died on March 24, 1989, at age 86, also while living at the Rockview Street house.

Joyce Fisher

Joyce Fisher

Joyce (“Joy”) Fisher was born on August 2, 1939, at New England Baptist Hospital. Joy recalled a story of how her mother wanted to name her Dean, a name that her mother saw on a tombstone at her family’s burial ground in Mansfield, most likely on the tombstone of Caroline Dean:

“My mother loved the name Dean. Dean was also the name of the man who, in the 1800’s, drove his cart and horses through the town of Mansfield in a drunken state, yelling and screaming. My grandmother was very much against alcohol. She said that if my mother named me Dean, she would have nothing to do with me.”

Though her ancestors in Mansfield were numerous, Joy explained that “I grew up in a very small family. I was an only child and my mother was an only child. My father had only had one brother, and he never had any children, so I have no cousins or brothers and sisters!” (Peace Drum Project, p. 13). Joy attended kindergarten through third grade at the Mary E. Curley School in Jamaica Plain and then spent fourth through sixth grade at the old Agassiz School on Burroughs Street. She remembers happy times as a child in Jamaica Plain:

“In the neighborhood I think there were 38 of us that ranged in age from 2 up to age 18, and there wasn’t a lot of traffic. We used to play ball over on Robinwood Avenue. On the corner of Robinwood and Rockview Street is a huge a green house, and the Lynches lived on the first floor, and there were five Lynch kids. Mrs. Lynch would sit on the porch, and she would watch over our playing of games, and she would be there if one of us skinned our knees or if there was a little dispute going on that she would have to monitor. There were open spaces that we could play hide and seek. Just interacting with one another. It was fabulous.”

Joy returned to the Mary E. Curley School from seventh through ninth grade and then attended the old Jamaica Plain High School on Elm Street where she was in the Honor Society. Joy shared with the Peace Drum Project, “My high school friends were Jean, Janet, Diane, Nancy, and Joan. But, my best friend was Jean. She lived two streets over and we were inseparable. We were best friends from Kindergarten through high school. She was just beautiful. She was actually in the Miss Massachusetts contest after we graduated from high school, and in high school she was voted ‘most beautiful.’ I was voted ‘best behaved!’” (Peace Drum Project, pgs. 15-16).

Joy (right) and her oldest friend, Sally Eldridge, at the Dedham Country and Polo Club, taken during Sally’s photo shoot with the Polaroid Corporation for the cover of their internal business magazine, August 1953

Joy’s home at 48 Rockview Street was a gathering place for her peers, and the site of her first date:

“[T]he church had a group they called the Christian Endeavor Group, and it was made up of girls and boys. We use[d] to have a meeting every Sunday night, and then we’d come back to my house. My mother would always have Coke on hand, and we would roll back the rugs back and dance. So I started dating one of the boys but I didn’t think of it as a date as such because we were a part of the group. Oh yes, his name was Dickey Mosher” (Peace Drum Project, pg. 18).

After Joy’s high school graduation, her mother wanted her to attend the State Teachers College at Boston because of the low tuition ($100 a year). Joy, however, decided to enroll at Boston University because they offered an associate’s program in business and secretarial studies. While working towards her associate degree, Joy was inspired to become a teacher after taking a class with Miss Roman, who became her role model. Miss Roman took a personal interest in her students and made everyone feel welcome. Joy saw the impact that she could have on students after seeing the positive impact that that her teacher had on her and the other students. So, at the end of two years, she stayed at BU and earned a degree in business education.

While a student at BU, Joy played on the Powder Puff football team. A photo of her posed in her uniform was published in the Boston Globe in April of 1961 : “We played one game a year. We would have a lot of practices with one of the fraternities. I think I was left tackle. I probably played for three years. During one of the practices, I got a black eye, and my picture appeared in the Globe. My mom was so embarrassed; she didn’t want anyone to know.”

From 1960 to 1967, Joy worked as a teacher at Katharine Gibbs College, a well-known secretarial school, at the school’s Boston location: “No matter where you went in the country, if you said, “I teach at Katharine Gibbs” people would say “Ahh! Wow!” It was so prestigious. I think I learned more teaching at Katharine Gibbs that I did [in] four years at BU because there was such a certain discipline about it, the way that people dressed, you could not wear a blouse and suit. You had to wear a dress. Your hair could not touch your shoulders. As a teacher I had to wear heels. I had to wear gloves and hats, back and forth to school, very professional.”

Part of her lessons were to teach the students shorthand: “What we would do for testing [shorthand] is that we would dictate. And you would dictate at different speeds. The class would have to take down the dictation. They would then have to go into another room, to a typewriter, where they would have to fling the carriage, and they would have to transcribe the material. They would be graded on how well they did. I think there was a certain artistry to it. But now it’s all so easy. You can go in and sit down, open up a Microsoft Word document, and you have this page in front of you. All you have to do is sit there and type. There is this little eye that goes out and says we are nearing the end of a line, go down to the next row. We are ending a page, they insert a new page for you. It’s a miracle!”

While teaching at Katharine Gibbs, Joy would think to herself that she was teaching others how to do office procedures, but she had not put those skills to practice herself in the workplace. So, she went to work as an office manager at a psychiatric hospital from around 1968 to 1977. She also worked as an Executive Secretary to the president of a leasing company that was part of the New England Merchants Bank. She returned to teaching later in life by leading computer classes.

In her free time, Joy loved to sew and knit. The dining room at 48 Rockview Street once served as her sewing room. She would clean off the dining room table, lay out her patterns, and put out an ironing board. Joy used the Vogue couture patterns, decorated the linings of her work, attached zippers by hand, and covered her buttons. She also did a lot of needlepoint. In her 80’s, she focused on knitting scarves and hats for the homeless and for friends.

Joy was also a baker and compiled a 50-page recipe book of desserts she had made. This author had the pleasure of spending many hours in Joy’s kitchen while she walked me through the steps of making lemon bars, almond bars, and chocolate chip cookie bars, all recipes from her book. She taught me short-cuts in setting up and putting away the ingredients, and tricks for making the ingredients work together. We would cut up the resulting dessert into squares to share with her neighbors, and me, her student baker.

Joy and Sister

Another of Joy’s loves were cocker spaniels, which were an important part of her childhood and adulthood. Her first dog was “on loan” from her parents’ friends, Bob and Caroline “Carol” Biggs, who ran a kennel in Dedham, Massachusetts (Bigg’s Kennel) where they raised champion American cocker spaniels. When Joy was four or five years old, the Biggses were looking for a temporary home for one of the dogs, named “Sister”. The Fishers had the dog for six months before the Biggses took Sister back to use her for breeding. The couple then gave Joy another dog, named Vicky, who Joy had until she was 17 years old. Vicky was followed by Sam, China, Shim, and Karma, all cocker spaniels.

Joy never married, but, as she explained, she had been engaged or proposed to many times by gentlemen across the globe, leading to a few broken hearts. She tells the story of a college boyfriend who took his banjo, jumped into his Volkswagen, and ran away from home after she broke off their engagement. She also told of a written proposal she received from a man she met in England in the 1960’s who, while washing his car, thought to himself, “She would be a great deal of trouble, but I really think I would like to marry her.”

Joy’s partner of 26 years, Bobby Greene lived with her at her home at 48 Rockview Street. Before moving in with Joy, Bobby was living in Roslindale but grew up in Hyde Park. He worked for the City of Boston Parks and Recreation Department as a gardener at the Boston Public Gardens and later at the Fenway Rose Garden. Joy explained to the Peace Drum Project how she and Bobby met: “I met Bobby in a roundabout way. I used to drive my mother and two neighbors to Forest Hills Station where they would catch the train to work. Then I would drive to Wellesley, where I was working at the time. One morning I noticed a man that I seemed to be driving past every morning at the same time – 7:10 a.m. After a few days, I just waved to him. Why not? Soon, we started waving to each other. Then one time, he waved me over and I stopped. We talked, then we started seeing each other, and the next thing we were together for 26 years” (Peace Drum Project, p. 21).

Bobby and Joy both loved to travel, so they explored Europe and the Caribbean together, including taking many cruises. Though they were very different from each other and had different interests, she found him a lot of fun to be with; she felt lucky to have those years with him. Joy shared: “I suppose Bobby and I could have married, but it was such a comfortable relationship, it didn’t seem to be any need for it. When I was in college, I think it was expected that one would marry and have children. I’m really glad I never had children. I think part of it was the fact that my father had Huntington’s chorea which is a neurological disease, and it can be passed down through the mother. So, even though I never had it, if I had children, I could have possibly passed it down. I always preferred dogs!”

Bobby passed away on June 12, 2003: “The hardest thing that I ever had to do in my life was say good-bye to Bobby. When he had cancer, he was in the hospital in a coma. Just being with him and trying to tell him what a role model he had been for me – and that it was OK to let go – That was very hard” (Peace Drum Project, p. 22).

Joy passed away on January 5, 2023, at age 83, from respiratory complications that had her in and out of the hospital and rehabilitation for a few months prior. However, 48 Rockview Street remained home – an oasis filled with art, history, love, and memories.

By Jenny Nathans, March 2023

More images are available in this supplemental Photo Gallery.

Sources

Ancestry.com

Architecture evaluated by Eric Dray, Historic Preservation Consultant

Boston City Archives

Boston Globe (1906, October 27). “Broke Plate Glass Front. Man Pulled Out Three Overcoats. Noise was Heard and Policeman Ran in Chase of Thief. Patrolman Fisher Praised for Capturing Him.”

Boston Globe (1909, May 12). “Off the Water Wagon. Devious Course of Thomas Cashman, the Driver, on Tremont St, Lands Him in a Police Station.”

Boston Globe (1922, September 23). “Beautiful Paintings Grace Church in Charlestown.”

Boston Inspectional Services

Fisher, Joyce. Interviewed by Kristie Simono, Katherine Colon and Miranda Desir. 2009. Peace Drum Project: The Elder’s Stories, Cooperative Artists Institute. http://www.tribal-rhythms.org/Joy_Fisher.pdf.

Private collection of the Fisher/Bang Family

Flint, Clara E. “Family History.” http://www.mhsma.org/Family-History.pdf.

Interviews with Joyce Fisher at her home at 48 Rockview Street, interviewed by Jenny Nathans

Jamaica Plain Historical Society maps https://www.jphs.org/maps-new

Caleb Johnson’s MayflowerHistory.com. “Peter Browne.” Accessed September 24, 2022. http://mayflowerhistory.com/browne.

The Mansfield (Mass.) News (1983, August 4). “A valuable acquisition.”

The Mayflower Society. “The Brown Family”. Accessed on September 24, 2022. https://themayflowersociety.org/passenger-profile/passenger-profiles/peter-browne/.

My Heritage, Library Edition

Dempsey, Claire W. “Fisher-Richardson House.” National Register of Historic Places Registration Form/Nomination Form. Massachusetts Historical Commission, January 7, 1998.

Newspapers.com

Suffolk Registry of Deeds

*A special thank you to Mayor Werner Schweizer of Klixbüll, Germany; and Bettina Dioum, archivist at the Landesarchiv Schleswig-Holstein, the state archives of Schleswig-Holstein, Germany, for their contributions to this research.

Footnote

This article uses Friedrich Marcus Bang’s American version of his first name, “Frederick,” since it is the name that appears in records that he drafted, or were published about him, while he lived in the United States.

Special thanks to Kathy Griffin for editorial assistance.