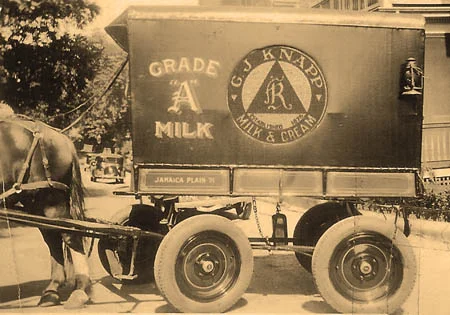

George J. Knapp Dairy

Where’s the Butterfat?

““Farm fresh milk from the Vermont cow to your door in 48 hours!””

Evolution of Knapp’s Dairy milk bottles. Courtesy Harold C. Knapp, Jr.

Thirty-two dairies serviced the greater Boston area in the 1930s. By the mid-1950s, there were only fifteen, due to industry consolidation, growth of supermarkets, packaging changes, home refrigeration, and changing consumers’ attitudes about home-delivered milk.

In the industry’s heyday, competing dairies’ home-delivery milk routes overlapped, so that on any Jamaica Plain street one might see wagons, pungs (sleighs) or trucks from a number of local dairies including Griffin’s, Deerfoot Farm’s, Robinson’s, George H.Ware’s, Westwood Farm’s, Whiting’s, Weiler-Sterling’s, Hood’s, Knapp’s, Whittemore’s or Herlihey’s, servicing the area’s fiercely loyal retail customers with milk and other dairy products. Government supports eliminated price competition, so service, reputation, and most importantly, butterfat content, were the keys to finding and keeping customers. A dairy’s customer list on any street was quantified as so many “quarts,” and that quarts list was a valuable component of a dairy’s assets.

Pung with 40 quart cans Feb 1923. Courtesy Harold C. Knapp, Jr.

.George J. Knapp Dairy, founded in 1876, promised “Farm fresh milk from the Vermont cow to your door in 48 hours.” Harold C. ‘Hal’ Knapp Jr., grandson of the founder, remembers the Saturday morning trips to North Station with his father, Harold C. Knapp, to meet the milk train delivering its cargo of raw milk from the Vermont milk co-op to local dairies. Meeting that train with his dad is just one of Hal’s many pleasant memories of running one of Jamaica Plain’s longest-lived dairy operations. Until it was liquidated in 1955, after nearly 80 years of home-delivery milk service, Knapp’s Dairy had enjoyed the reputation of having one of the highest butterfat contents in greater Boston.

The Knapp family’s lives outside the milk business brought them into close contact with several Jamaica Plain icons including August Haffenreffer, Miss Seeger’s School, Miss Marguerite Souther and her dancing school, the Loring-Greenough House, the Tuesday Club, a long-running national antiques magazine, and the Boston antique dealers’ market.

The Beginnings

Milkman circa 1915. Courtesy Harold C. Knapp, Jr.

In 1876, Hal’s grandfather, George Jacob Knapp (1856-1931), quit the cabinet-making business and started George J. Knapp Dairy at 75 South Street, at the corner of an alley that became Atwood Square, Jamaica Plain. Later, he and his wife, Emma (1863-1944), moved to 24 John A. Andrew Street, where they found a large barn on a much bigger lot. From there they started building a customer base that would eventually include fourteen communities around Jamaica Plain.

Emma held the home together during the long hours of George’s work at the dairy and after long, happy and prosperous lives together; George and Emma Knapp were buried in Section 28, Lots 1874 and 1875, at Forest Hills Cemetery.

George and Harold Knapp, ca 1906. Courtesy Harold C. Knapp, Jr.The Knapps had three children, George, Robert and Harold C. Knapp. Harold was born in 1895. George entered the textile business so Robert and Harold C. Knapp would later assume control of the dairy. Harold was the more active partner and he ran the business until his health and the economic viability of door-to-door milk delivery began fading in the 1950s.

Harold C. Knapp’s son, called “Hal” due to the obvious confusion of two Harold C. Knapps in the household, worked in the dairy in his early and teen years, but later declined his dad’s offer to take over. So, in 1955, the Knapp Dairy’s assets, comprised of trucks, processing equipment and the route-lists, were sold to several local dairies, thus ending Knapp Dairy’s 80-year unblemished run in the intensely regulated milk industry.

Hal Knapp

Hal Knapp was born in June 1934 at Faulkner Hospital in Jamaica Plain. His only sister, June, was born in 1929. When Hal was born, his parents, Harold C. and Julia Anna Knapp, were living in a second floor apartment at 11 Aldworth Street, a short street that runs north from Centre Street to Dane Street. Their house backed up to Hal’s maternal grandfather’s house at 18 Dunster Road.

George and Harold Knapp, ca 1906. Courtesy Harold C. Knapp, Jr.

Hal, just four years old at the time, remembers the 1938 hurricane and that his dad, whom his mother had called home from the dairy because of her fear of the raging storm, just barely got their 1938 four-door Packard sedan into the garage before a huge oak tree fell across the driveway where he had stopped just seconds earlier.

The first-floor tenant at 11 Aldworth Street was Lt. Eddie Leonard of the Boston Fire Department. Eddie’s station was near Roxbury Crossing where he had a traditional Dalmatian in the building that also housed a five-story tall hose-drying rack. Besides designing the Boston Fire Department’s first Rescue Truck, Eddie was a fabulous cook and baker and often shared his delicious baked goods with his upstairs neighbors.

Hal’s dad was interested in fire stations because a fireman named “Goggie” MacDonald had saved his life when he was a child. One day, when he lived at 75 South Street, Hal’s dad heard a fire alarm so he jumped on his bicycle to follow the horse-drawn pumper. His bike’s wheels got caught in the streetcar tracks and he fell in the path of another onrushing fire wagon. Firefighter “Goggie” MacDonald picked up Hal’s dad just as the wagon ran over the bike! Hal has always wondered about the origins of Goggie’s unusual nickname and how he might not be here if not for Goggie MacDonald’s timely rescue of his dad.

Hal attended the Agassiz School, where, due to his diminutive size, he experienced some bullying before moving on to the Dexter School in Brookline, the Noble and Greenough School in Dedham and Boston University, where he earned a degree in aeronautical engineering. Along the way he worked for the Larz Anderson Auto Museum moving cars from their storage facility in Cambridge to a planned-but-never-realized satellite museum next to the Children’s Museum on Boston’s waterfront. Also, at his father’s urging, he learned to wrestle to defend himself from the frequent onslaughts of upperclassmen and the bigger kids in the neighborhood. From early on, however, Hal’s off-hours were mainly spent working in and around the family dairy, learning every aspect of the milk business.

50 Eliot Street

Hal’s mother, Julia Anna Knapp, who worked for a Boston law firm and was fond of restoring old things, found an old house at 50 Eliot Street that she felt could be restored to its former glory. It had for a time been a private school whose growing enrollment forced unplanned haphazard expansion by adding on rooms, porches and a third floor without a master plan of any kind. This was Miss Seeger’s School for Girls. Miss Seeger may have been related to the famous World War I poet, Alan Seeger, who wrote “I Have a Rendezvous with Death.”*

The Seeger school closed in 1936 due to the Depression and two spinster ladies, probably Alice and Josephine Hewins, later operators of the school, were living there when Julia Knapp came along. When the Hewins sisters showed the house to Julia, she found an old photo of the property in the attic and decided that, should they end up owning it, she would remove the add-ons and restore it to the beautiful single-family home shown in the photograph. The Knapps bought the house and Julia hired an architect, Albert Clark, who lived across the street from the house, to draw up plans and specifications for Julia’s renovation project. Hal Knapp still has those Clark documents.

With the plans and specs in hand, Julia approached the First National Bank’s Jamaica Plain branch for a $10,000 (quite large then) mortgage to do the renovation work. The bank was appalled by the plan to remove rooms and reduce the size of the house so they refused the mortgage, despite the fact that the bank handled Knapp Dairy’s and the family’s personal accounts! Unfazed, she found a bank in Roxbury that gladly lent her the money. Soon, after word of the unusual renovation project was out, the First National Bank came to Julia, hat-in-hand and anxious to lend money to be associated with the now well-known remodeling project, but she was pleased to decline their offer, thank you.

During the renovations the Knapps moved to the Jamaicaway in an apartment building next door to Mayor James Michael Curley’s beautiful home. Hal’s aunt lived next door in an identical apartment building. The apartment buildings were so close that the Knapps visited the aunt by jumping across the flat roofs that were nearly touching.

Their lease on the Jamaicaway apartment expired before 50 Eliot Street was ready, so in 1940 they had to move in prematurely and finish the renovations while living there. Hal’s dad was running the seven-day dairy operations and couldn’t participate in the renovation project but Hal, at six years old, could pull nails from salvaged boards and tacks from stair treads. He still has the nail puller in his collection of antique tools.

Hal’s dad did, however, find time to rebuild bicycles at 50 Eliot Street during the war while Julia began furnishing their new house with antiques. Among those antiques are some bow-back Windsor chairs that had been used by the firemen at the Jamaica Plain fire house on Centre Street. Those chairs, which Hal still has, were wired to the seat at the bottom of the spindles because the firemen would lean back and tip the chairs to rest on the fire station wall while they were relaxing between fires. The wiring prevented the spindles from popping out of their sockets.

1936 horse-drawn wagon with pneumatic tires. Courtesy Harold C. Knapp, Jr.

Harold Knapp and early DIVCO ca 1929. Courtesy Harold C. Knapp, Jr.

The Milk Business

Running a local dairy, much like a dairy farm, was a seven-day operation. Hal’s father, Harold C. and his uncle, Robert, took over the business when the founder, George Jacob Knapp, retired. The operational challenges they faced were daunting and included managing a business office with internal and external auditors, handling billing and collections, security issues with drivers handling cash, maintaining a small herd of horses and later, buying, operating and maintaining a fleet of trucks. Other duties included operating expensive and complicated milk-processing equipment, hiring and training drivers while maintaining mutually agreeable labor relations, dealing with health and other municipal inspections as well as Rabbinical inspections for Kosher requirements, and maintaining proper controls throughout the processing and delivery of perishable bottled milk with one of greater Boston’s highest butterfat contents, all within 48 hours of its arrival from the Vermont milk co-op.

Harold Knapp and early DIVCO ca 1929. Courtesy Harold C. Knapp, Jr. Hal’s dad was the driving force in the second-generation operation and he began upgrading the aging equipment and delivery system right away. In 1929 he bought Knapp’s first DIVCO (Detroit Industrial Vehicle Company) truck designed specifically for the milk and other multi-stop home delivery businesses. The DIVCOs were in production from 1926 until 1986 with gasoline engines. Originally designed as an electric vehicle in 1922, the 1926 re-design incorporated a LeRoi gasoline engine. The early trucks could be operated from the front, rear or from outside the truck on either running board. They were steered by a tiller, i.e. no steering wheel. A horizontal handle like a boat tiller turned the vehicle, while the brakes were operated by hand-levers mounted on the outside of the truck. Three separate pedals, levers, and handgrips controlled the acceleration. In 1937 the body was re-designed and remained unchanged in the snub-nosed configuration for the next 50 years. Surprisingly, there is great interest in these old trucks, especially the split-wheel tire rims that now command high prices for use on racecars.

DIVCO wanted to capture the local milk truck business, and since Hal’s father had quickly learned to operate their trucks, DIVCO asked if he would demonstrate the truck to other local dairies. Harold agreed and performed the demonstrations so well that DIVCO achieved their objective and Harold earned a nice discount on all of his DIVCO truck purchases.

1936 horse-drawn wagon with pneumatic tires. Courtesy Harold C. Knapp, Jr.The last horse-drawn wagon at Knapp’s was retired in 1942 and Hal has one of the kerosene taillights from it. The horses had been kept in stalls at 24 John A. Andrew Street. The last horse to work a Jamaica Plain route was “Major,” a large, good-natured animal with that special skill found in many door-to-door delivery horses. Major knew the route so well that after the first stop, the driver would simply hang up the reins and Major would, without further urging, move on to the next customer, knowing exactly where to stop along the rest of the route. If a customer had cancelled delivery for that day, the driver simply uttered two tongue-in-cheek ‘clicks’ and Major would walk on and stop at the next customer’s house.

Some of Knapp’s DIVCO trucks were painted green and cream, but most were all white. A specialty wagon-painter called Somerville Wagon Company painted the Knapp fleet. The blue-lettered, white background, porcelain signs with the scripted company name “George J. Knapp Dairy” were removed from the horse-drawn wagons and remounted on the new DIVCO trucks. The motorized fleet of specialty trucks allowed the expansion of the company to include fourteen municipalities, among which were: Jamaica Plain, Roslindale, Roxbury, West Roxbury, Milton, Dedham, Boston, Dorchester, Hyde Park, Chestnut Hill, Quincy, and Brookline.

A very effective post-war equipment upgrade by Hal’s resourceful dad was the replacement of the original coal-fired steam boiler used in pasteurizing the milk and cleaning the bottles with an oil-fired Clayton Steam Generator from a World War II aircraft carrier. It had been used to make steam for the aircraft launching catapults on the ship and like much no-longer-needed war materiel it was sold as “surplus” after the war. The self-contained Clayton Steam Generator was reliable, fuel efficient, easy to maintain and ensured that the recording thermometer on the pasteurizer was at all times seeing the Government mandated temperatures required for milk-safety.

An Early Start in the Milk Business

Hal started working at the family dairy at a very young age. His 1936 calendar-boy pose, at two-years old, marks the beginning of his 20-year connection with the business. He recalls his father waking him early Saturday mornings to go into Boston to meet the train carrying raw milk from the five-dairy milk co-op in East Wallingford, Vermont, and off-loading 40-quart cans of un-pasteurized milk. This Saturday morning trip reprised his father’s trip with his grandfather many years earlier. Later, the raw milk would be delivered directly to Knapp’s Dairy in shiny, glass-lined, tanker trucks eliminating the Knapp’s two-generation trip to Boston.

Hal Knapp at Science Fair 1951. Courtesy Harold C. Knapp, Jr.As he grew to teenaged years, Hal’s duties at the dairy included: unloading and gassing the 10 company trucks, washing the trucks inside and out, performing minor repairs on the truck fleet, stocking shelves with supplies used in the bottling process, cleaning the milk room and pasteurizing vats, disassembling and reassembling the complicated Manton-Gaulin homogenizing machine, washing bottles and cleaning the bottle washer, boxing eggs, going in at night to turn off the ice machine and other equipment, cleaning the roof-mounted coolers that cooled and recycled the cooling water used in the pasteurizing process and performing the all-important butterfat test. Hal demonstrated that butterfat testing process in a 1951 school Science Fair exhibit that earned him the nickname ‘bottles’ because of his unique pronunciation of that word during his demonstration.

One of Hal’s more amusing chores was making special deliveries in the dairy’s beautiful new 1948 Ford pickup truck with its gold and red highlighted pin striping. Another pleasant memory is picking up sandwiches for the drivers and sitting in their circle on milk crates as they swapped work, war, and personal stories. The sandwiches came from either Bob’s Spa on South Street or the closer Carraber’s Variety Store at the corner of Call and Williams Streets.

The drivers were a critical part of the dairy’s success, functioning as salesmen, customer service representatives and providing the face of the company in the community. Their day-long stop-and-go deliveries in a stand-up truck included many three-deckers. It was not easy work delivering the standing order of glass-bottled milk, cream, butter, eggs, etc. and retrieving the empty bottles to be washed and reused. Hal remembers John Walsh, Barney Cook, the Demling brothers and a Mr. Buckley as some of the long-term highly regarded Knapp’s drivers. The Knapp’s drivers were rewarded with crisp cash bonuses at Christmas time – along with a hand-written note of thanks from the owner.

Occasionally, Hal would work on a route with his dad as a ‘striker,’ covering a driver’s day-off. A ‘striker’ in those days was a young boy who rode on a truck delivering milk, bakery products, newspapers, or other commodities on a regular delivery route. The driver would stop at a store or residence and the striker would run full-tilt to drop off the milk, cakes, newspapers or whatever, at the customer’s door or store while the driver was setting up the next delivery. Striking was usually good for $1.50 a day plus a nice lunch at Terminal Lunch in Forest Hills, depending on the driver, while the driver got home for a nice early dinner, depending on the striker.

Hal remembers his father’s kindness to one of the dairy’s neighbors, the Ristuccias, owners of Bob’s Spa at 128 South Street, who lived at 16 John A. Andrew Street during WWII. It seems the Ristuccias needed new tires and wondered if the dairy, which had a wartime rationing allowance for tires because of their exempt industry status, could help them? Hal’s father immediately arranged for some of the dairy’s used tires to be mounted on the Ristuccias’ car for which they were very grateful ever after.

Hal also remembers that Weiler-Sterling’s dairy had an exceptionally fine welder who could expertly perform the difficult process of silver-soldering stainless steel fittings used throughout the milk processing equipment in a dairy. Hal’s dad asked if he could ‘rent’ the welder and Weiler-Sterling said sure – a clear sign of the mutual respect and friendship that existed between small competitors in the milk business. The seconding of that particular employee happened several times over many years. Years later, when Weiler-Sterling was being sold, Hal’s father attended the sale and Mr.Weiler asked if there was anything he would like for himself. Hal’s dad spotted a fine old Regulator Clock on the wall and Mr. Weiler said to help himself to it. Hal’s dad treasured the old clock as a reminder of the fine people he met in his long career in the milk business. Many of those same people were members of the local Dairyman’s Association that met regularly in Sherborn, Massachusetts.

Knapp’s biggest retail competitor was Hood’s Milk who processed milk from several locations and herds. United Farmers competed at the wholesale level by offering small grocers a signing bonus of a beautiful new refrigerated milk chest - a deal that Knapp’s could in no way match. It was a sign of the times ahead.

The End of an Era

In 1955, Hal’s mother finally convinced his father to get out of the business to stop the serious deterioration of his health caused by the long stressful hours running a very demanding business. So, after nearly 80 years in business, Knapp’s Dairy sold off the major assets and the company was closed.

The trucks, equipment, and routes were sold to several different local dairies. The Company name and goodwill couldn’t be conveyed to a new owner because the small dairy business was being consolidated and absorbed by bigger players as customers’ buying habits were changing and margins were shrinking. No one wanted to run a small local dairy anymore.

A New Life for Dad

Once the company was sold and the pressure lifted, Harold’s health immediately improved. He missed the milk business though and soon, because of his fine reputation as a dairyman, he was flattered by an offer from a Needham, Massachusetts, dairy owner to come and ‘troubleshoot’ his dairy. Harold happily accepted the offer, but soon, because he took on all that dairy’s headaches as if they were his own, his health deteriorated again. So, he finally quit working and spent the rest of his life involved as a church Elder, refinishing furniture for his antique-collecting wife and fixing damaged gadgets for the Breck’s Gardening shop at Chestnut Hill. He and his wife, Julia, retired to a condo in Chestnut Hill. Notwithstanding the early damage to his health, Harold C. Knapp lived to see his 95th birthday, remaining bright and alert to the very end in 1990.

Mom Had a Life Too!

Hal’s dad wanted his wife, Julia, to stay home with the children while he was running the dairy, so she quit her job for a Boston attorney. She did, however, conduct internal audits of the Knapp Dairy’s books, picked up Evelyn, the bookkeeper, and drove her to work, and helped with other office related tasks.

Later, however, Julia’s interest in antiques landed her a job with The Magazine Antiques, attending antique shows at various venues in Boston such as the Mechanics’ Building on Huntington Avenue, the Copley Plaza and Vendome Hotels and the like, where she set up a booth and sold subscriptions to the famous, long-established and still-in-print, antiques magazine. This exposure increased her knowledge of the antiques business and antiques themselves. Hal still has the antique furnishings Julia used to set up the booth and even he got exposed to the antiques world when he was 16 and would use the Knapp’s Dairy truck to deliver antiques for the dealers in the shows his mother attended. Hal had learned from his mother how to properly handle antiques and the dealers at the shows noticed that careful handling. Before long, Hal had an antiques delivery business going.

Julia was also a member of the Tuesday Club and she and Harold ran the annual auctions at the Loring-Greenhough house with Hal and his sister, June, acting as runners. Hal’s dad also ran the hot-dog concession at the auctions. Naturally, Knapp’s Dairy trucks did the hauling and delivery of the antiques.

Miss Marguerite Souther **

Miss Marguerite ‘Rita’ Souther, a Jamaica Plain icon, operated the widely known dancing school at Eliot Hall for over 50 years. Hal’s sister, June, worked there as an instructor and his mother, Julia, through her antiquing interests, membership in the Tuesday Club and the auctions at Loring-Greenough House, got to know Miss Souther very well.

When Miss Souther decided to sell her large house at 44 Allandale Street, a second- generation house built by her father, Charles H. Souther, on the site of her grandfather’s former estate called “Allandale,” she asked Julia to appraise the houseful of antiques she had inherited and acquired over many years.

44 Allandale Street. Taken from undated postcard.

During one of the appraisal visits, Miss Souther said to Hal’s dad: “Harold, look under my bed, there are two guns under there that you can have.” One of the guns was a .22 caliber Derringer and the other was a Colt Target pistol. Harold never asked why they were there.

Miss Souther sold the house to Faulkner Hospital and moved to Longwood Towers, leaving behind a legacy of old-school manners and mores passed on to her thousands of students. Her former property at 44 Allandale Street is now home to the Springhouse retirement community.

August Haffenreffer

Hal’s maternal grandfather, George Hoerrner, worked at the American Brewing Company (ABC) brewery on Heath Street as a stationary engineer, i.e. an engineer licensed to run fixed, or stationary, machinery. George Hoerrner insisted on conscientious lubrication of the equipment used to brew and refrigerate beer and was thus nicknamed “Oil Can.” He lived on Lawn Street in 1905, at 149 Fisher Avenue in 1912, at 100 Magazine Street in Roxbury in 1925 and finally at 18 Dunster Road, Jamaica Plain.

Oil Can went to work for the Haffenreffer breweries and became a close friend of August Haffenreffer, grandson of the founder, Rudolph Haffenreffer. George Hoerrner worked for Haffenreffer’s for 40 years, being responsible for the equipment at several Haffenreffer brewing and storage sites. At retirement, August asked him what he’d like besides the proverbial gold watch. Oil Can replied, “I’d like that copper-covered bar in the ‘customer’ room used to entertain wholesale customers in the basement at the ABC brewery on Heath Street.” August said that one-half of the 16’-long bar was already spoken for, but the other half was his. George also got the engraved Waltham watch. George Hoerrner died in 1947.

The Military

Hal remembers a major event in his life was declining his father’s offer to take over the dairy in 1955, which would have provided a draft deferment. However, Hal had seen how the stress and long hours had practically destroyed his dad’s health and he didn’t want to go that way. Also, the consolidations in the industry were eliminating the small operators which didn’t bode well for a career in milk. Hal’s plans for his military obligation were uncertain until his draft notice arrived and triggered his immediate enlistment in the Army as a Helicopter Inspector/Mechanic. He went to Fort Dix, New Jersey, for basic training and was then sent to an Air Force base in Texas for helicopter training. He then chose Stuttgart, Germany, as his deployment destination where he served two-and-a- half years from 1955 to 1958.

In Stuttgart Hal trained NATO helicopter pilots in the response procedures to be used when mechanical problems forced an emergency landing. He also developed guidelines for the immediate grounding of a helicopter with operating problems. He personally became adept at identifying potential problems that would require a helicopter to be grounded and repaired before it could be flown again.

In one incident, he earned an on-the-spot promotion to Sergeant from a General Officer. Hal noticed that oil seeping from the tail rotor on a certain helicopter seemed to have fine aluminum particles in it. He quickly deduced that the rotor unit’s aluminum mounting hardware was deteriorating and if not corrected it could break away causing the helicopter to crash, so he immediately grounded the helicopter. The helicopter was the base commander’s who arrived at the scene and demanded to know who grounded his helicopter and why. Hal somewhat nervously explained his rational for grounding it and then, with the General’s approval, Hal had a mechanic strip the unit whereupon his diagnosis was instantly confirmed. When the General saw the proof of Hal’s diagnosis, he was duly impressed and ordered Hal’s immediate, on-the-spot, promotion to Sergeant.

As he was being discharged, Bell Helicopter Company, with whom he had worked closely for the past couple of years, offered him a job as a Tech Rep out of their Dallas office. Hal accepted, but just before leaving for Dallas, a local company offered him a better job doing payload analyses on various Medevac-type helicopters that Hal had worked on in Germany. He accepted the far-better offer from Microwave Development Laboratories in Wellesley and stayed three years. Another promotion was offered by Lab for Electronics Company, which he accepted. He then went with the Hazeltine Company as a Contract Administrator. While at Hazeltine, Hal explored several ideas for possible patent applications. He left Hazeltine after a short stay there and from August 1965 he worked at Raytheon for the next 27 years.

Looking Back

Hal’s most significant memory of the Knapp’s Dairy years is that it was a rewarding, but very tough business, demanding constant close attention to details and enormous vigilance to constantly ensure the safety of the product. The damage done to his dad’s health and the consolidation of retail milk suppliers that prompted Hal to decline his dad’s offer to take over the company was a decision he does not regret. He has great love and respect for his dad and the wonderful example he set for Hal’s own life. He loved being able to help his father, even as a little boy, and fondly remembers the many hours they spent together getting milk to the thousands of Knapp’s Dairy customers in and around Jamaica Plain.

Now retired at Chatham, Massachusetts, Hal and his wife of 47 years, Carol (Sinclair) of Warren, Rhode Island, who retired from a 40-year nursing career at New England Baptist Hospital, enjoy boating and restoring and maintaining antique cars and tools.

By Peter O'Brien

*Jamaica Plain Historical Society Oral History: David A. Mittell, 2004

Business card from the Weiler-Sterling Fams Co, another big dairy operation in JP in the first half of the 20th century