Shoes & Brews: An Irish Family in Jamaica Plain, 1880-1940

This article is based on a slide show presented by Susan Steele at the Loring Greenough House in Jamaica Plain on January 7, 2020. It follows the Glennon family during the industrial era of 1880-1940 in Jamaica Plain and Roxbury. Employment in the Thomas G. Plant Shoe Factory and the Burton Brewery provided the family with opportunity and hardship. The article follows the transformation of the family and Hyde/Jackson Squares through the decades.

Our story begins 3,000 miles away across the Atlantic Ocean. Taghmaconnell Parish is in the southern part of County Roscommon, Ireland. In the 1870s this was an agricultural area. An early description of Taghmaconnell’s 12,000 acres stated that “the land is badly cultivated… there is a considerable portion of bog, and limestone abounds.” The farming couple John and Catherine Glennon, along with older sons Timothy and Patrick, worked this land. They struggled to provide for a family of eight. John Glennon was paying rent on just over an acre of land. County Roscommon had been hit very hard by “The Great Hunger,” otherwise known as the potato famine. The county had lost thirty-one percent of its population in the famine decade of 1845-1855, and the population was continuing to decline. These difficult circumstances may have contributed to John Glennon’s death at age 52.

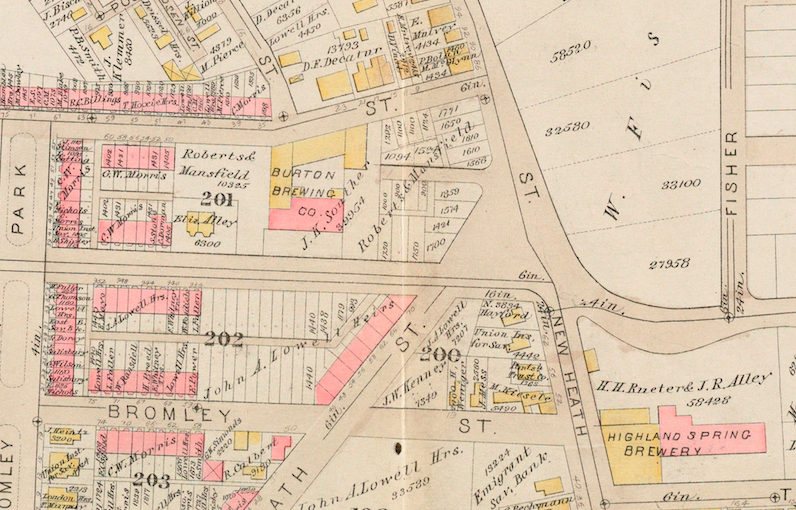

Map of Glennon neighborhood in 1884

John Glennon’s death precipitated family change. Timothy, the oldest son, departed for America. He arrived in Boston by 1874 and was soon employed in one of the many breweries in the Roxbury/Jamaica Plain area. Timothy may have sent word of employment opportunities to his brother Patrick. Patrick also emigrated and was living near his brother the following year. Their mother, Catherine Glennon, and sisters Winnifred, Mary, and Katie, joined Timothy and Patrick by 1880.

Mary Kenney

While the Glennons were adjusting to life in Boston, Mary Kenney was getting ready to make her own journey. Mary was the oldest of ten children of Malachy and Sarah Kenny. She was born in 1861 in Drum, County Roscommon. Drum was only nine miles away from Taghmaconnell. Family history sources have Mary coming to Boston alone but later being joined by four sisters and one brother. Mary’s brother found employment in the breweries and three of her sisters’ husbands also became brewery workers. Mary may have met her future husband through the community of Irish workers at the breweries. Mary Kenney married Patrick Glennon in January of 1880 at St. Joseph’s Church in Roxbury.

St. Joseph’s Church was in Roxbury and so was Patrick’s and Mary’s new home. In 1880, Wards 21 and 22 were part of Roxbury, while the rest of Jamaica Plain was part of West Roxbury. The extended Glennon and Kenney families lived on Heath Street, Minden Street, and later on Mansur Street. In contrast to the rural areas of County Roscommon, this was an emerging industrial area dense with worker housing.

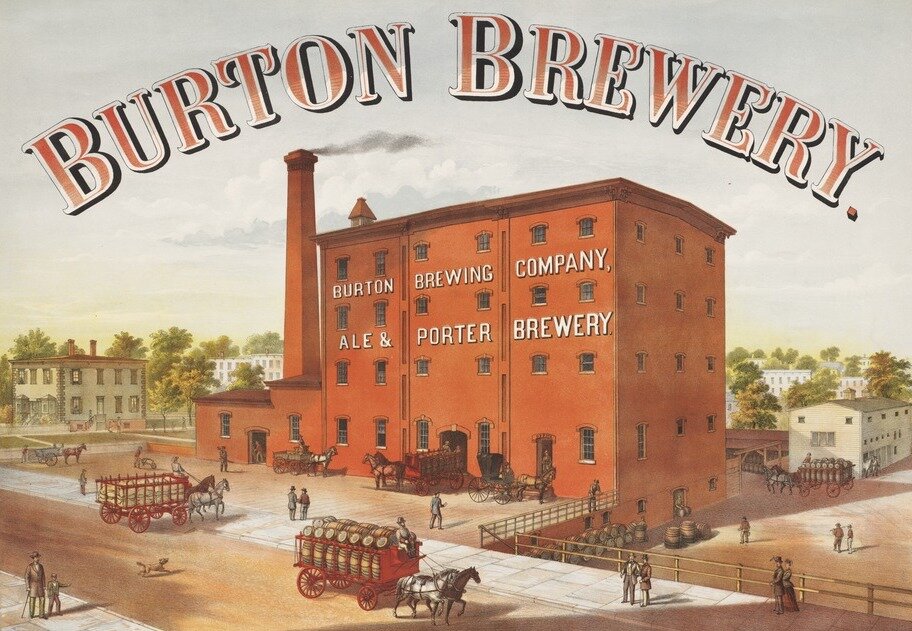

In 1884, there were several breweries within close walking distance of the Glennon home at 92 Heath Street. Two of those breweries were the Burton Brewery and the Highland Spring Brewery. These were just two of the twenty-four breweries in the Jamaica Plain/Roxbury area. Patrick Glennon worked at the Burton Brewery.

What was brewery life like for the Glennon brothers and the Kenney family? Patrick worked as an unspecified laborer in the initial years. In the early 1900s some of his time was spent on delivery wagons. He drove the wagons through loading doors at the bottom of the building. In addition to the finished product coming out through these doors, other materials such as hops, grains, barrels and bottles went in. The interior of the brewery was dusty, wet and smelly. Back-breaking work included lifting the heavy sacks of hops and grains and loading large barrels onto wagons. In 1880 the work day was twelve to fourteen hours with breaks for meals. The product produced – beer – was available to the workers in unlimited quantities. Long hours of labor and fatigue could lead to excessive use of beer. There are some reports of exhausted workers throwing themselves down on hop sacks for a few hours’ sleep between shifts.

The Burton Brewery was located on the corner of Parker & Heath Streets.

Patrick Glennon

It seems likely that Patrick was aware of the dangers of his job. In November of 1896 Patrick Glennon took steps to protect his family. He took out life insurance with the Massachusetts Catholic Order of Foresters. In addition to providing life insurance, this fraternal order was also a social group. Patrick joined the St. Francis Court (or chapter) of the Foresters. There were many other Irish immigrants among the membership of St. Francis Court. Patrick was 39 when he applied for membership. He gave his occupation as “laborer in brewery.” His application revealed information about Patrick’s birth family – his parents and siblings. Patrick stated that his father died at age 52, his mother at 48, and his brother, Timothy, died the previous year at age 42. Awareness of his brother’s death and Patrick’s own responsibility for six children ages one to fifteen, may have prompted his membership.

The medical exam portion of Patrick’s application detailed a physical description. Patrick was 5 feet 10 inches tall and weighed 200 pounds. He was described as having a “vigorous appearance.” Other questions asked if the applicant used spirits, wine or malt liquor, and to what extent. Patrick answered, “two glasses of beer a day.” He was judged a “good risk” and approved for membership in the Foresters.

Six years later in 1902, his wife Mary, age 39, also took steps to protect the family when she joined Blessed Sacrament Court of the Foresters. Mary’s neighbor, Catherine Hennigan, proposed her for membership. Both women would have walked down to Columbia Hall on Centre Street to pay monthly dues and participate in social activities.

In the 1900 census the Glennons were living at 10 Mansur Street along with the Hennigan family, the Leonard family, and three boarders. Nine of the adults at 10 Mansur Street were born in Ireland. There were other adults born in Ireland, and a number of adults born in Germany, living on Mansur Street. Many of the German and Irish adults gave their occupation as brewery workers. Patrick Glennon, now 41, was listed as the owner of the multi-family property. Daughter Mary, age nineteen, was working as a bookkeeper. Five Glennon siblings were at school and two, Madeline and William, were under the age of four.

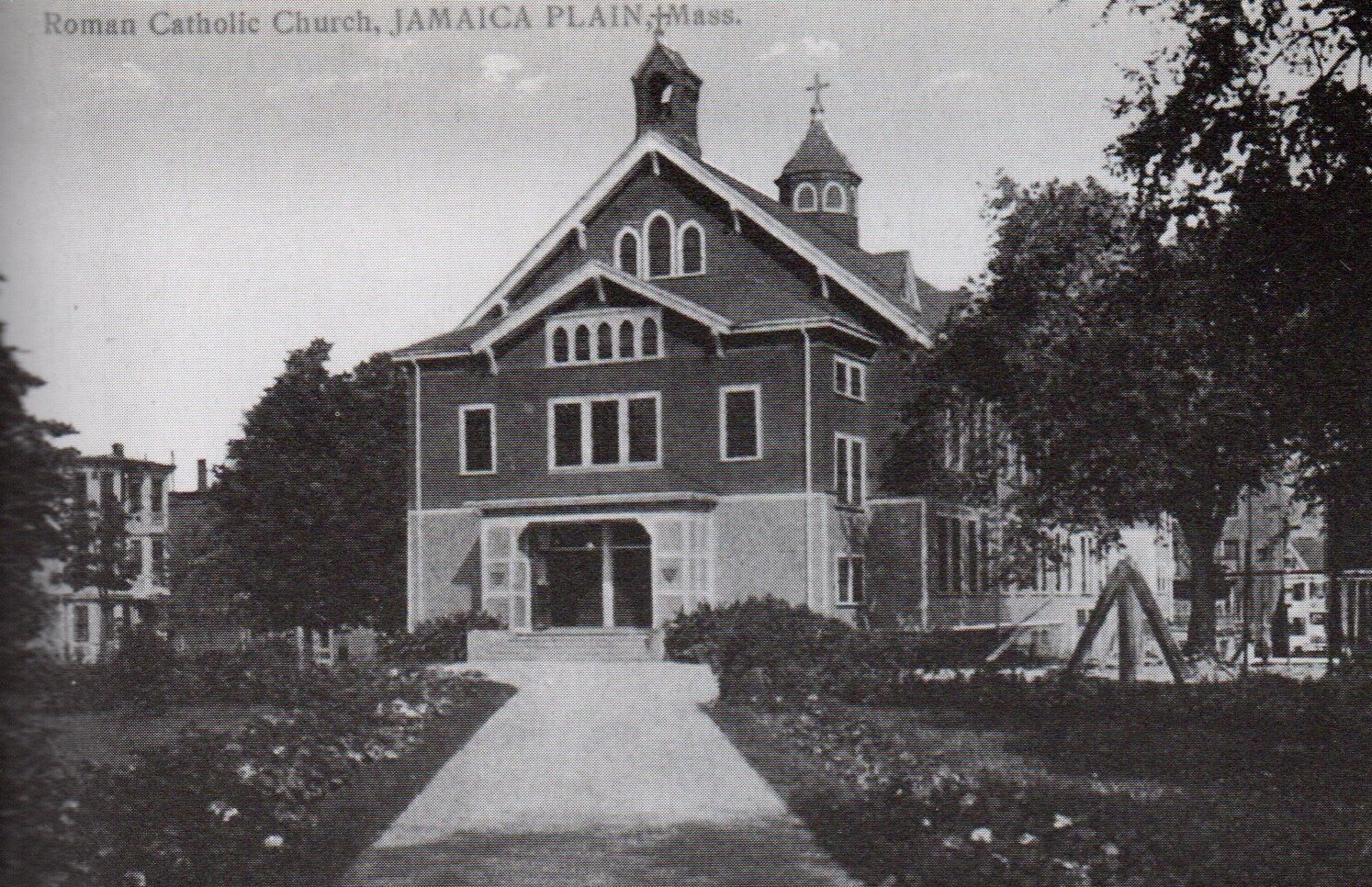

From 10 Mansur Street, the Glennons had a short walk to Catholic Mass at Blessed Sacrament Church. Blessed Sacrament Parish was founded in 1892, and the small church was soon serving a thousand members. The founding pastor, Reverend Arthur Connolly, was a driving force and eventually created an entire campus of buildings on the Centre Street site. In addition to Columbia Hall, a rectory, primary school and convent were added to the campus. Later on, Rev. Connolly had a secular building named for him – our own Connolly Branch of the Boston Public Library.

The Catholic schools on Blessed Sacrament campus were built too late for the older Glennon children. They had attended the Jefferson School on Heath Street and the Lowell School on Centre Street. By 1910, three children were working. Daughter Mary was then a stitcher at a shoe factory along with sisters Loretta and Winifred. Patrick Glennon was a foreman in the brewery. The Glennon family was still living in the house at 10 Mansur Street, although there were fewer people in the multi-family household. The Hennigan family had moved, but they would play a later part in the story of the Glennon family.

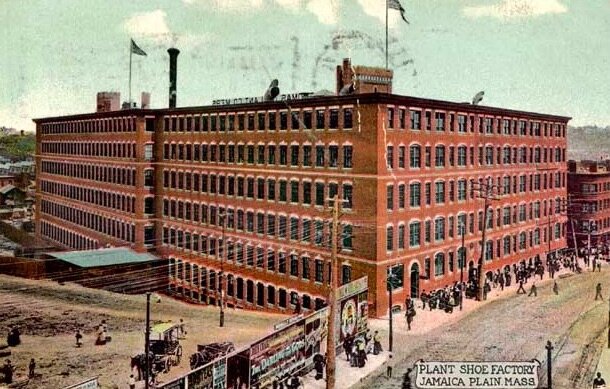

Plant Shoe Factory

The Glennon sisters Mary, Loretta, Winifred and Katherine all worked at the Plant Shoe Factory. When Thomas G. Plant moved his shoe factory from Lynn to Jamaica Plain in 1897, he created a huge complex with floor space of 16 acres. The factory would produce over three million pairs of shoes yearly and employed over 5,000 workers at its peak. The company was a non-union firm. Thomas Plant was considered an “enlightened capitalist” who embraced some early reforms, including the nine-hour work day. The women’s shoes created by the factory were labeled “Queen Quality,” and Plant named the umbrella association providing worker benefits the “Queen Quality Athletic Association.” A list of just some of the worker benefits includes: a dining room, library, barber shop, first-aid room with nurse, roof garden, dance hall with piano, billiards, bowling alley, athletic teams, drama and musical groups, noonday rest garden, and children’s nursery. The nursery was added during World War I to accommodate additional women needed to replace men leaving for the armed service.

The Glennon girls would have been able to take advantage of many of the Plant Factory amenities, including walking in the “noonday rest garden” – part of 13 acres of grounds designed by the firm of Frederick Law Olmsted. Mary and Katherine Glennon were featured in a 1906 Plant Factory minstrel show. Katherine Glennon was a soloist. Mary joined her sister and others in a musical sketch entitled “Queen Quality City.”

All of these activities would have provided a pleasant respite from the tedium of workday tasks. Plant Company press releases provided a management perspective on positive conditions at the factory. An oral history from a stitcher at another Jamaica Plain factory provided a different description of conditions still existing for some in the early 1920s: “Factory windows did not provide enough light for those working in interior areas. Racks of shoes could block light and air. Women had to be careful not to get hair or clothing caught in belts that ran some of the machinery. The air was dusty and there was pressure to keep production moving.” Mary Glennon was the sister whose tenure was the longest at the shoe factory. She was there from some time before 1910 through 1930 and perhaps beyond. Her position through 1930 was listed as shoe worker.

The pressure to meet production quotas could also affect safety standards. There were worker injuries and deaths at the Plant Factory. A 1908 article detailed an incident when a flywheel burst, sending fragments flying into workers and also bursting steam pipes. An incident the following year caused one death and severe burns in three men. Concerns about such incidents may have been a factor in a movement by leather cutters to unionize. Workers had to sign statements confirming that they would not join a union as a condition of their employment. In 1907 cutters went out on strike, protesting this employment clause. There was pressure on other workers to withhold support for the strikers. The cutters were fired as well as any relatives they had working in the factory.

The Glennon girls probably experienced a range of both positive and negative working conditions. Loretta Glennon’s tenure at the shoe factory was much shorter than that of her sister Mary. Loretta (or “Etta” as she was called in the family) was working as a stitcher in 1910 producing “Queen Quality Shoes.” Exposure to shoe design may have influenced Etta’s own flair for fashion. Etta’s youngest sister Madeline remembered skipping school to accompany her big sister on outings. Shoe shopping was one of Etta’s favorite activities! Etta left the Plant Factory in 1917 to marry and move to her husband’s home in Allston.

While she was at the Plant Factory, Etta and her siblings would have been expected to contribute to the family income. However, Etta was able to spend some of her salary on shoes and other items. Fashionably attired, the Glennons were ready to participate in activities outside the home. Blessed Sacrament Church sponsored many religious and social activities. A 1901 article described a church picnic held in a grove near Amory Street. Besides refreshments, there was singing, dancing and a tug-of-war between brewery workers. Patrick Glennon would have been in his late forties. He was still laboring at the brewery so could have been a tug-of-war team member. Mary Glennon used her skills to help run a whist party for the church.

The original wooden Blessed Sacrament Church built in 1891 at the corner of Centre and Creighton Streets near Hyde Square.

Blessed Sacrament Parish had continued to grow and in the early 1900s was serving 1,100 families or 6,000 individuals. The small wooden structure was stretched well beyond capacity. Father Connolly recruited parishioners to help conduct a massive fundraising campaign for a new church. The magnificent new edifice was completed in 1917. Blessed Sacrament complimented the other Catholic church at the opposite end of Jamaica Plain – St. Thomas Aquinas. Our Lady of Lourdes was established in 1908. Together these parishes served a very large group of Irish Catholics.

The new Blessed Sacrament Church completed in 1917 at 361 Centre Street, in Jamaica Plain.

As the parishes grew so did the Glennon family. In 1918 three sisters were married and there were then five grandchildren. Winnifred lived in Jamaica Plain. Catherine and Etta had moved from Jamaica Plain but came back to family gatherings on Mansur Street. The family came together in early 1918 before brother Joe departed for service during World War I. Joe’s departure preceded other separations that would alter the Glennon household.

The Glennon family, circa 1918.

In 1918 Patrick Glennon was still working at the brewery driving a delivery wagon. His daughter Madeline recalled neighborhood children running out to see her father when he came home from work. Patrick would reach into his pocket and give all the children some change. Madeline remembered her father as a “very jolly man with the best disposition of anyone I’ve ever met in my life.” All of this changed in April of 1918.

Patrick Glennon was driving his team of horses when he had a collision with a street car. He fell from the wagon and sustained injuries that disabled him and left him bedridden. Madeline remembered that her father couldn’t get out of bed and was unable to return to work. Patrick died on December 27, 1918. His death certificate documented contributing factors of chronic myocarditis and hepatic cirrhosis. Did the free beer provided by brewery have an effect on his liver? It is unclear – some Glennon descendants have a genetic condition that can affect the liver. A few months later in 1919, the Foresters issued a $1,000 death benefit check for Patrick’s beneficiary, his widow Mary Glennon. Five adult children were still in the household. The thousand-dollar check would have paid for a funeral and helped the family catch up with expenses incurred during their father’s illness.

In 1920 some members of the Glennon family were commuting to jobs outside of Jamaica Plain. The matriarch, Mary Glennon, age 61, was the head of household and owner of 10 Mansur Street. Daughter Mary was still working in the shoe factory. Helen was a salesgirl in Conrad’s Department Store on Winter Street in Boston. Sarah Madeline was a telephone operator at New England Telephone, and her brothers Joe and William were both clerks in a broker’s office. The married sisters left the household. Winnifred lived on School Street in Jamaica Plain, while Catherine was in Milton and Etta was in Allston.

Seven years later, Mary Glennon, age 64, died of carcinoma of the stomach. The thousand-dollar Forester death benefit was divided among all the adult children, each receiving $125. By then, the youngest daughter Madeline was married and living in Quincy.

As one sister left the household, another returned. In 1930, Winnifred moved back to 10 Mansur Street with her three children and husband John O’Neil. Sisters Mary and Helen as well as brothers Joseph and William were also living in the family home. Mary was still at the shoe factory. Helen and William were working in sales – dry goods and insurance. Joe was then a musician in an orchestra. The white-collar jobs these siblings held were a contrast to the blue-collar occupations of most of their neighbors.

In 1940 Mary, Helen and Joseph Glennon were still in the family home. Continuing the transition from factory work, Mary joined the white-collar ranks and became a clerk doing auditing. Helen was in sales, and Joe was a musician but also teaching music. The next generation entered the workforce. Winnifred’s son, Joseph, was a clerk in State service.

The 1942 photograph above shows other changes in the family. The two older ladies in the middle and back row are the sisters Winnifred and Etta. In front of Winnifred is daughter Dorothy who entered the St. Joseph order of nuns. On Dorothy’s right is her sister, Winnifred, who would also join the St. Joseph order. In the back row to the right of Etta is her son Ed, daughter Mary, and son-in-law Arthur. The baby is Etta’s granddaughter, Maureen. As these changes took place in the family, the home neighborhood was also undergoing a transition.

Patrick Glennon’s death at the end of 1918 preceded big changes for the breweries in Jamaica Plain/Roxbury and across the nation. Prohibition began in 1920 and wasn’t repealed until 1933. The Burton Brewery became a bottler of Moxie and was able to stay in existence for a number of years. In 1940 the brewery building became part of a large parcel of land bordered by Heath, Bickford and Walden streets. This area which contained numerous residences and several factories was acquired by the Boston Housing Authority. The area was cleared and in 1941 plans were approved for seventeen apartment blocks containing 420 residences. We now know this development as the Mildred C. Hailey Apartments.

The Plant Shoe Factory building went through several transitions. Thomas Plant sold the facility to another shoe company in 1910. It continued to manufacture shoes but changed owners several more times. By 1970 it was home to several small businesses, art studios and apartments. On Feb. 1, 1976, an arsonist shut off the sprinkler system and set several fires throughout the complex. After demolition of the unsafe structure all that remained was the smokestack on the left side of the building. That was removed when the Hyde Square Stop & Shop complex was built.

Joe and Patrick Glennon

Back on Mansur Street, other changes were happening. The oldest daughter, Mary Glennon, died in 1949. Helen and Joe remained in the family home a few years longer and then moved into an apartment on South Huntington Avenue. Sister Winnifred and her husband also moved to the South Huntington building. Why did they leave their home on Mansur Street?

The houses on Mansur Street were demolished in preparation for construction of the Hennigan School and playground. Mansur Street has disappeared under the large school layout. Do you remember those 1900 neighbors of the Glennons – the Hennigan family? A descendant of that family was James W. Hennigan, state senator and the namesake of this school. His son, James Hennigan was also very active in politics and his grandniece, Maura Hennigan continues to carry out the political tradition in the family.

The Glennons were lifelong members of Blessed Sacrament Parish. Baptisms, marriages and funerals took place within the beautiful structure. In 2004, the Archdiocese of Boston closed Blessed Sacrament. It remained shuttered and empty while other parts of the church campus were redeveloped. In 2014, the church building was purchased by the Hyde Square Task Force and later reopened as the Latin Quarter Cultural Center, a place for celebrations.

So, with all those transitions, Shoes & Brews make way for Places to Learn, Places to Live and Places to Celebrate. I also want to celebrate the Glennons, the family that inspired this presentation. We have followed this family through many transitions: leaving Ireland, establishing a new life here, working hard, contributing to their community, and always embracing family. There were those who were together until the very end, and those who kept “home” and Jamaica Plain in their hearts.

Susan Steele

January 2020

Credits

Family photos and oral history courtesy of Judith Barrett

Boston Public Library Digital Commonwealth Collection: Burton Brewery, Blessed Sacrament Church (second building); Boston Public Library, Leventhal Digital Map Collection, 1884 Roxbury / Jamaica Plain Historical Newspapers

Jamaica Plain Historical Society: photo -Blessed Sacrament Church (first building), “Boston’s Lost Breweries”; “Thomas G. Plant Shoe Factory Fire”; “Bromley-Heath Public Housing Development History”

Select List of Resources

Massachusetts Catholic Order of Foresters Mortuary Records, University Archives & Special Collections, Healey Library, UMass Boston, http://blogs.umb.edu/archives/collections/foresters/

Local Attachments: The Making of an American Urban Neighborhood, 1850 – 1920, Alexander van Hoffman

Not so long ago: oral histories of older Bostonians, Lawrence Elle

https://archive.org/details/notsolongagooral00elle/mode/2up

Remember Jamaica Plain?

https://rememberjamaicaplain.blogspot.com