Baseball in Jamaica Plain

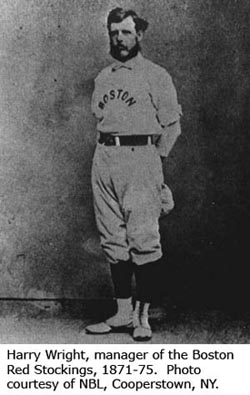

The beginnings of baseball in Boston and its first connection to Jamaica Plain are found with Harry Wright and his brother George. Harry was born in England. George, thirteen years his junior, was born in New York City. Their father, Samuel, was a professional cricket player in New York and both boys started with that sport before switching to baseball. Harry played and managed the Cincinnati Red Stockings, the first professional baseball team, to a run of 76 consecutive victories during the 1869 and 1870 seasons. When the players there asked for more money and attendance faltered after finally losing to the Brooklyn team, the Cincinnati team disbanded. Harry then came to Boston in 1871 and, with his brother George, co-founded the Boston Red Stockings. These Red Stockings would later become the Boston Braves.

Harry lived at 7 New Heath Street, a reasonable commute to the South End Grounds where the Red Stockings played.

The Red Stockings came in second place in 1871, their first year in the National League. Then they won the championship in 1872, ‘73, ‘74 and ‘75. Wright’s four consecutive years of winning essentially taught the whole country how to play baseball!

The star pitcher of the Red Stockings during those winning years was Albert Goodwill Spalding. Spalding pitched and won 56 games in the ‘75 season. In 1876 he jumped to Chicago for more money, and he was a star there too! He then became manager and co-owner of the Chicago Whitestockings. We’ll hear more about Albert G. Spalding later.

In 1876 we find Harry Wright listed on Pond Street. He apparently lived there only one year because we next find him at 1 Highland Park Avenue, Roxbury, which is gone now. He then moved to 9 Highland Park Avenue, which still exists as a nice row house with a beautiful view overlooking the Stony Brook Valley. Thus, since Wright was an early inductee to the Baseball Hall of Fame as the founder of professional baseball, and the person responsible for nearly half the game’s concepts of play that exist today, Jamaica Plain can rightfully share bragging rights, along with Cincinnati, to this great baseball icon.

Even more intriguing than the Jamaica Plain connection to one of the co-founders of professional baseball is the little-known fact that baseballs were manufactured here. This is documented in 1869 and 1870 advertisements we’ve found for baseballs made by one L.H. Mahn with a Jamaica Plain, Mass., PO Box given for the source of the “Mahn Dead Ball.”

Louis Mahn perfected the manufacture of a good “standard” baseball. Up to that time baseballs were very expensive and only one was used for the entire game no matter how beat-up it became during the game. It was then awarded to the winning team as sort of a trophy. Since there were no standards, the early balls varied widely, resulting in significant differences in pitching and hitting results. For a time, each side used their own ball for their half inning.

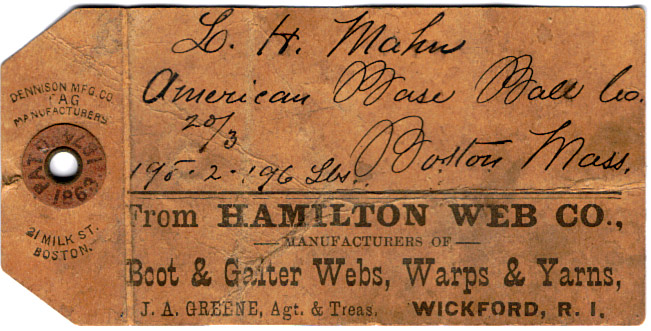

A tag from the Hamilton Web company based in Wickford, Rhode Island, and addressed to L.H. Mahn, American Baseball Company. The tag was found at 1 Marlou Terrace and was once attached to raw materials used to make baseballs. Image provided courtesy of Herb and Mary Nolan.

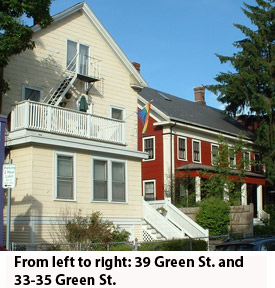

Mahn’s standardized ball was developed under a March 21, 1872 patent that he bought from a John Osgood. The ball was built in two hemispherical sections and sewn together with an interlocking double herringbone stitch in a figure eight loop so that if one stitch broke, the whole ball didn’t unravel. Mahn manufactured the first balls at 39 Green Street starting in 1874. 39 Green Street is a private residence now.

Mahn never owned the building at 39 Green Street. He rented it while residing as a tenant in one side of the house next door at 33-35 Green Street, owned by George Williams. 39 Green Street was built later on the lot adjacent to 33-35, that was also owned by Williams. The tax records of that era showed not only the owner but also tenants and functional uses of taxed properties. Thus for 1874 and 1875, we find 39 Green Street taxed as a house, stable and baseball factory with Louis Mahn listed as the tenant. Before that, in 1871-1873, it was listed as just the house and stable, so we can conclude that 39 Green was purpose-built as a baseball factory.

After 1875 Louis Mahn disappears from Green Street and buys a house on a plot on Lamartine Street in the area of Cheshire Street and Chestnut Avenue. Mahn ultimately owned six buildings at this location. The two buildings fronting on Lamartine Street are numbers 307 and 311 Lamartine. There were four buildings in the rear, one of which was a stable and another taxed as a baseball factory.

Since all six buildings on Mahn’s plot were built at about the same time, it is difficult to determine which of the existing buildings there now was the baseball factory. It was most likely the building located on Marlou Terrace on the left of 307 Lamartine. It is speculated that Marlou Terrace got its name from the contraction of Marie and Louis Mahn’s first names. Marie F. Mahn has been verified as Louis’ wife.

So now we might ask why Mahn stopped making baseballs on Green Street and moved to Lamartine where he bought land and built five buildings in addition to the one already there? The evolving history of baseball at the time may shed some light on this.

In 1876, when Mahn moved from Green to Lamartine Street, he sold the patent for the Louis Mahn baseball to Albert G. Spalding. Spalding wanted to get into baseball equipment and sporting goods in general. He bought Mahn’s patent, and since he, Spalding, was the co-founder of the National League in 1876, he was able to manipulate the league to get an exclusive monopoly on supplying Spalding (Mahn) baseballs to the National League. This monopoly created a great increase of business for Mahn, so he had to move to the larger quarters that he built on Lamartine Street. Spalding later formed the well-known sporting goods firm of the same name in Chicopee, Massachusetts.

Harry Wright, Louis Mahn, and a fellow named George Howland - sometimes called Holland - were partners in a baseball retail store on Washington Street at the corner of Kneeland Street. Known as Wright, Howland, & Mahn, sellers of baseball goods, they continued in 1878 to ‘79. They then vacated 30 Kneeland Street and moved to 765 Washington Street in 1880 and ‘81.

In 1881, with the Red Stockings fading, Harry and George Wright moved to Providence, Rhode Island, where they co-managed the Providence Grays.

Louis Mahn was still manufacturing baseballs all the way up through 1883 and ‘84. He disappears from the city directories in ‘1885, ‘86, ‘87, and then reappears in Boston, in 1888; but not manufacturing baseballs anymore, according to that year’s Directory. Following his baseball-manufacturing career he went to work for a cash conveyance system company. You remember those pneumatic tube systems that carried your cash in a brass cylinder, with a big WHOOSH, to the main office and then sent back your change and a receipt? (Jordan’s, Filene’s, Gilchrist’s etc. all had them.) Mahn worked for the largest company in that field, Lansom Company; headquartered in Boston, as an executive handling European sales. Mahn had a good run and is truly a significant part of Jamaica Plain and Major League Baseball history.

More Jamaica Plain baseball connections are found at Fordham Court, a large apartment building on South Street just south of Anson Street. The owner of the Red Sox, Joseph Lannin, owned Fordham Court, and might even have built it. Lannin owned Fordham Court from 1914 to 1920 when he sold it to some investors in Brookline. Lannin sold the Red Sox to Harry Frazee in 1916.

Fordham Court was rumored to be the home of some of the Red Sox players during their heady years when they were winning the World Series. It was even suggested that Tris Speaker might have lived there. He was a famous Red Sox player until traded away to save money in 1916. Others have said that Babe Ruth might also have lived there. Babe Ruth, of course, was a pitcher for the Boston Red Sox before being traded away in 1919. We haven’t been able to substantiate these stories but newspaper reports show that Tris Speaker attended the third annual St. Thomas Field Day at the Carolina Ave playground, and that Joseph Lannin contributed a loving cup to the winner of a local baseball game on that July 4th, 1915 event. We have pretty much confirmed, however, that neither Speaker nor Ruth lived at Fordham Court.

Another major leaguer, Eddie Waitkus, was born in Cambridge and died in Jamaica Plain. He played for the Chicago Cubs, Philadelphia Phillies, and Baltimore Orioles, and then again for Philadelphia, with four years off during the war. Waitkus’ story was a sideline in the Robert Redford movie, “The Natural.” He was shot by a mysterious, unstable, young woman in a hotel room. Waitkus survived and lived until 1973 in Jamaica Plain, leaving an 11-year major league career, from 1941 to 1955, on the books.

Other players include Babe Twombley, born in Jamaica Plain, who played with the Chicago Cubs from 1920 to 1921 and Leo Callahan, who played two years with the Brooklyn Dodgers and later the Philadelphia Phillies. Callahan was born in Jamaica Plain in 1890 and played from 1913 to 1919.

A player known as Shorty D. was born in Halifax and died in Jamaica Plain in 1971. Shorty played one year with the St. Louis Browns.

And Johnnie Tobin was born in Jamaica Plain in 1906. He played one year for the New York Giants in just one game and got up to bat just one time!

In addition to the named contributors to baseball, we note some of the early baseball rules that might surprise present-day fans. For example, scores of the early games played without catcher’s masks, gloves or mitts of any kind, could run-up to 72 to 56! Balls and strikes were not usually called, but when they were, it took nine balls before a walk was awarded. The idea was that the pitcher was obliged to put the ball in play and the fielders were bound to work the play after that.

Other differences included the freedom to bunt foul as many pitches as you could, without penalty, until you got a pitch you liked. This was changed in the 1890’s to the current rule that an attempted bunt that goes foul after two strikes, puts the batter out. Also, professional teams consisted of exactly nine players, so the pitcher had to pitch every game. And since there was no base stealing allowed, the catcher was usually situated 20 to 25 feet behind home plate.

There were regional rule differences also. For example, in New York a ball caught on the first bounce was an out, whereas in Boston you had to catch it on the fly. In addition, the New York rules allowed beaning the base runner with the ball that was known as “soaking the runner,” and it was a putout. And, underhand pitching prevailed until the 1890’s. Around this time stealing was allowed, four balls earned a base on balls, and umpires were added to each of the bases. Other innovations beginning to evolve were the use of hand signals, spring training down south, and sadly, the deliberate attempt to keep Black Americans out of professional baseball which existed until 1947 when baseball’s segregation was finally broken by Jackie Robinson. The Red Sox were the last team in the league to admit a black player. Pumpsie Green, the first black Red Sox player, signed with the Red Sox in 1959.

We can’t leave the Jamaica Plain connections to baseball without mentioning an intriguing gentleman named Gottlieb Burkhart. He owned a huge brewery in the Mission Hill area, which, for a time, was known as the North Jamaica Plain section. He had eight large six-story buildings producing brews known as Red Sox beer and Pennant Ale. The backs of the labels for these beverages held the complete schedule of the Red Sox. Burkhart lived on Boylston Street, on a large estate, which has become the John F. Kennedy School. His breweries existed up to the 1950’s.

So ends our survey of baseball in Jamaica Plain and its connections with the Major Leagues. Once again, diverse and important Jamaica Plain connections can be found in a national institution that enriches the quality of American life for all of us.

This article is based on a lecture given by Michael Reiskind on June 15, 2004, with additional information provided by Kenneth A. Perkins. Editorial assistance was provided by Chris Globig, Charlie Rosenberg, Amy Rothman, and Peter O’Brien.

Copyright © 2006, Jamaica Plain Historical Society.